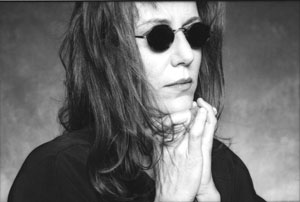

With 20/ 20 hindsight, it makes perfect sense that Jennifer Warnes’ exquisite 1986 album, Famous Blue Raincoat: The Songs of Leonard Cohen, became a critical and commercial success. After all, Cohen is now widely regarded as one of the great songwriters and poets of the modern era, and the always-underrated Warnes was enjoying a hot streak that included singing two Best Original Song Oscar winners—“It Goes Like It Goes,” from Norma Rae, and her inescapable chart-topping duet with Joe Cocker on “Up Where We Belong,” from An Officer and a Gentleman—and another nominee, “One More Hour,” from Ragtime.

But in early 1986, when work began on Famous Blue Raincoat at Hollywood Sound, no major labels wanted to touch it. Cohen had almost no profile in the U.S. at the time—he was, and still is, most popular in Europe, though the U.S. has finally caught up in recent years. And a few high-profile songs notwithstanding, Warnes had not exactly been burning up the charts with her solo albums.

The idea for the album—which became known, colloquially, as “Jenny Sings Lenny”—had been germinating for several years. Warnes went way back with Cohen—she was a backup singer on his 1972 tour, remained close friends with him, and then worked on Cohen’s 1979 album, Recent Songs, his world tour of that year (which played Europe, but not North America) and on his Various Positions album in 1984. The Recent Songs album and tour also brought the other main force behind Famous Blue Raincoat into Warnes’ orbit: bassist Roscoe Beck and the Austin-based jazz/fusion group he was part of, Passenger. The band backed up Cohen for a number of tracks on the album, and then formed the nucleus of Cohen’s backing group on the tour (captured well on the Field Commander Cohen live album, released in 2001).

Warnes and Beck became close over the course of the tour, and it was on long bus rides between cities and in hotels all over that the seeds were planted to someday make an album of Cohen’s songs, couching the songwriter’s lyrics in more challenging and imaginative settings. “I thought the lyrics deserved elegance,” she says today. Over time, those discussions evolved into something more concrete, but the proposed album still lacked a home.

“MCA said, ‘Who would buy that?’ and the truth is I didn’t know,” Warnes says with a laugh. “But then this small indie label [Cypress Records] took it and, even though we had a very, very small budget to work with, we got it rolling. It was the first record that Roscoe or I had ever produced, separately or together, and we just said, ‘We can do this… can’t we?’ And we did, with the help of some of the finer people in the city; we managed to pull it off. Roscoe and I felt it doesn’t matter if you haven’t done it before if your vision is clear and you’re committed.”

It helped that both Beck and Warnes were very well-connected in L.A. Warnes had been recording there since the late ’60s and worked with many of the city’s A-list session players, and the more recent L.A. transplant Beck had also established himself as a musical force around town; in fact, he regularly played at local nightspots with a group of session heavies that included guitarist Robben Ford, drummer Vinnie Colaiuta and keyboardist Russell Ferrante—all of whom turn up on Famous Blue Raincoat, along with a couple of Beck’s former associates from Passenger, pianist/arranger Bill Ginn and saxophonist Paul Ostermayer. (Other local luminaries who helped out included synth titan Gary Chang, keyboardist/arranger Van Dyke Parks, percussionist Lenny Castro, bassist Jorge Calderón, guitarists Fred Tackett, David Lindley and Michael Landau, and a host of backup singers associated with Ry Cooder—Willie Greene, Arnold McCuller, Bobby King and Terry Evans. Signing on to engineer was Bill Youdelman, who was well-known for his expert live recording work (as well as his studio chops), having worked on such projects as Sting’s Bring on the Night, Warren Zevon’s Stand in the Fire and Weather Report’s exceptional 8:30.

“Initially, I made a deal with Hollywood Sound to record there for six weeks,” Beck says, “but I think it was the end of the first day of recording that Billy Youdelman announced to me that he refused to work there—that the microphones were bad and he didn’t like anything about the room. And I said, ‘Well, I’ve already made a deal for six weeks.’ And he said, ‘Get out of it. I’m going to take you over to The Complex.’ We ended up staying at Hollywood Sound for three days and worked on a few songs there. ‘Bird on a Wire’ and ‘Coming Back to You’ were both tracked at Hollywood Sound with live vocals. We had already rented a microphone [an AKG C12 favored by Youdelman for Warnes’ vocal] from The Complex for the few days we were at Hollywood Sound. I had to wiggle out of the deal and then go talk turkey with [Complex owner] George Massenburg.” From the outset, Beck and Warnes knew they wanted to record their album of Cohen songs on one of the new digital multitracks that were quickly gaining a foothold in L.A. studios, “but our budget was a real problem,” Beck says. “To do what we were doing in those days, which was renting a Sony [3324] 24-track digital machine, you had to spend $600 a day for the machine alone. Fortunately, the label we ended up going with [Cypress] had already purchased the new Sony machine. They wanted to sell the record as an all-digital record, as CDs were in their infancy and they saw that as a great selling point. We took the Sony into The Complex and sometimes rented a second one, too.”

The Complex got its start in the late ’70s, when engineer and audio inventor George Massenburg built a three-room recording facility for Earth Wind & Fire. He equipped the control rooms with custom consoles that were, naturally, outfitted with his soon-to-be-legendary EQs, preamps, advanced automation systems and other peerless gear. “The sound in there was just phenomenal,” Youdelman enthuses. “Part of it was the acoustics, but most of it was George’s equipment—to this day, nothing I know of could equal the electrical performance of the consoles at The Complex. A lot of the reason the record sounds so good and so clean is through George’s hard work on that equipment.”

Warnes, Beck and Youdelman were determined to record the album as “live” as possible in the studio. “There was something about the feeling of ‘live’—as Ry Cooder called it, ‘the goddamn joy!’— that really took me by the throat,” Warnes says. “I knew that record had to have the feeling that there was a place where it was recorded and there were real people playing and we were capturing some magic in the studio.”

Most of the basics for the album were tracked live (with Warnes even singing a couple of keeper vocals with the group), but that was not the case with this month’s Classic Track, “First We Take Manhattan.” The song was one of three Cohen songs introduced on Famous Blue Raincoat—the others were “Ain’t No Cure for Love” and “Song of Bernadette” (which Warnes co-wrote and, unlike the other two, Cohen never recorded). Like so many Cohen songs, “First We Take Manhattan” is quite cryptic lyrically—you’ll find fan and critic interpretations that say it is about political and/or psychic extremism, the dispossessed, or, 180-degrees from that, about the perils of the music business. Warnes has her own ideas, but notes, “Leonard works from a stream-of-consciousness sometimes, and I don’t always know what the lyrics mean. I just need some seed of truth to be there.” It’s a driving, modern-sounding track, a stirring kickoff to the nine-song album.

Beck says, “The first thing recorded in 1986, once we were officially making the record, was a click track and a sequenced bass for ‘First We Take Manhattan,’ which I hurriedly constructed after hearing the rehearsal the day before our first tracking date, and having the uneasy feeling that it wasn’t going to happen the following day. Vinnie [Colaiuta] had set up the night before and got his sounds, so I asked if he would do a favor and play to this click track and sequencer. Jennifer went into a booth and did a vocal, as well. Vinnie was familiar with the song because we had rehearsed it previously. He played that drum track in one take and I just smiled real big and said, ‘There’s my drum track.’”

The next element to be added to the song was Stevie Ray Vaughan’s loose, bluesy guitar part, which contrasts so nicely with the metronomic drive of the main rhythm. Beck knew Vaughan from Austin, and each had sat in with each others’ groups in the past, so when Beck heard that Vaughan was going to be at the Grammy Awards in L.A. in February 1986, he tracked him down at his hotel and asked if he would play on “Manhattan” that very night. Vaughan had not brought a guitar to L.A., but agreed to use one of Beck’s Strats. A session was booked at the Record Plant, with Tim Boyle engineering, and in the wee hours of the morning, Vaughan laid down several takes for Beck and Warnes.

From there, Gary Chang overdubbed his synths, Beck added a final bass part, Robben Ford contributed some slinky guitar, there was a touch of percussion, and Warnes re-sang her lead vocal, either on the AKG C12, or a mic Youdelman discovered late in the album sessions—a B&K testing mic that lived in the ceiling of The Complex. Several other engineers were involved along the way, too, including Larry Brown, Charlie Paakkari, Paul Dieter, Paul Brown, Steven Strassman and Csaba Petocz, and a couple more studios—The Enterprise and Salty Dog.

The album was mostly mixed at Amigo Studios in North Hollywood by Frank Wolf (along with Beck) on Studio B’s SSL, with additional mixing work by Massenburg, Larry Brown and Henry Lewy on certain tracks. The slightly unsettling passages of spoken German at the beginning and end of “First We Take Manhattan” was an idea of Lewy’s—“We wanted to snag people’s attention, and that was Henry’s call,” Warnes comments.

When the album was released in late 1986, “Bird on a Wire,” “First We Take Manhattan” and “Ain’t No Cure for Love” garnered considerable radio play on different formats, and the album as a whole was embraced by Cohen’s followers, Warnes’ fans and also, more generally, audiophiles who were impressed by its deep and pristine sonics. The record breathed new life into Cohen’s career in the U.S., and also helped establish Warnes as a serious artist in ways that her previous chart triumphs had not. Coincidentally, in 1987 she also scored a Number One hit with her duet with Bill Medley from the mega-popular soundtrack for Dirty Dancing, “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life” (another Oscar winner!).

Famous Blue Raincoat continues to earn respect and new fans with each passing year. A 20th anniversary edition, remastered by Bernie Grundman and featuring several bonus tracks, came out in 2007, and a new a vinyl version (also mastered by Grundman) will be released this year. It remains perhaps Warnes’ crowning achievement.

“When you have the proper alchemy and all the secret good wishes of everyone, fireworks can happen,” Warnes says, “and you know you’re on to something. About midway through the record, we knew it was great. Nobody was shouting about it at that point, but Roscoe and I knew we were sitting on something fantastic.”

Online Extras: More from Jennifer Warnes, Roscoe Beck and Bill Youdelman about the making of Famous Blue Raincoat.

Beck on meeting Cohen and Warnes: “I met Leonard in early ’79 when he was making the Recent Songs album, a record that Jennifer would later overdub vocals on. He was maybe halfway through the album when his producer, Henry Lewy, who was also Joni Mitchell’s producer, brought me in to play on a couple of things. And that resulted in Henry bringing in my entire band at that time, which was called Passenger. After we finished up the Recent Songs album with Leonard, we went back to Austin, and while we were there, Jennifer put her vocals on the record [in L.A.]. We accepted Leonard’s offer to tour that fall, so shortly before I met Jennifer, I heard that she was going to be on the tour [as a backup singer], which maybe seemed a little odd, because she had hit a song on the radio, ‘I Know a Heartache When I See One’ [from her album Shot Through the Heart].”

Beck on the genesis of the album: “Jennifer was bold enough to propose the idea to her label at the time, Arista, and it was not well-received. [Laughs] Sometime later, that relationship ended, and then, after a couple of movie [song] successes, around 1984, she signed a deal with MCA and—she might not even remember this—at the first meeting she proposed two ideas: to do a record with Ladysmith Black Mambazo [pre Paul Simon’s Graceland!] and this other, a record of Leonard Cohen material. MCA then dropped her, and she found herself without a label. So we decided to go ahead and just start recording some of the [Cohen] material anyway.”

Youdelman on the tracking sessions: “Most of it was done live with Jennifer in the room at the same time. That was particularly important to get a good feel. If you piece things together, the band usually doesn’t lock up as much as they do when they play with each other. The whole record was done with the idea of high fidelity or maximum fidelity from my point of view, so dynamic mics wouldn’t have been used very often; nothing very loud. We probably used a lot of C-12s and 67s, though I can’t remember many specifics. I think on ‘Bird on a Wire’ I used Neumann KM-88s [as drum overheads] which are nickel-membrane microphones. The rest of it was more or less routine. I’m kind of minimalist. I might even go for Schoeps stereo CMT 501s, and I think George had one—he actually got his after he heard mine, and I could have used that over the drums and maybe a kick drum, but that literally could have been it.”

Beck on Youdelman: “Billy was a great live engineer, and credit to all the other engineers who worked on the record, too—Tim Boyle, Larry Brown and George Massenburg. Billy was there the longest doing the tracking. He got great sounds and didn’t need an overabundance of tracks to get them. He really impressed me that way.”

Warnes on her first exposure to “First We Take Manhattan”: “Leonard played a working track of the song over the phone from Montreal, to Roscoe, who recorded it. We were excited to have a brand new composition for the album. I think one possible inspiration for the ‘we’ in ‘First We Take Manhattan’ may have come from Leonard’s familiarity with the Guardian Angels [a Manhattan citizens’ non-violent militia who voluntarily patrolled New York streets for a period]. There was something interesting about these street-wise kids wearing berets and saying, ‘We’re going to stop crime.’ So that may be what got the horse out of the stall [in terms of writing the song], but then he had all these other images, too, of course.” Beck: “Leonard had played me an earlier version of the song with the working title, ‘In Old Berlin,’ but his revised version, ‘First We Take Manhattan,’ absolutely stunned me when he played it over the phone. It was such a departure musically, from his previous work.

Leonard Cohen on “First We Take Manhattan,” as quoted in the book Leonard Cohen in His Own Words (Omnibus Press, 1999) by Jim Devlin: “It’s a kind of outsider speaking; it’s somebody who never thought much of what he got. I can’t identify with it completely. In the context of the song it’s just the voice of enlightened bitterness. [It] is a demented, menacing, geopolitical manifesto in which I really do offer to take over the world with any like spirits who want to go on this adventure with me.”

“The chorus [“You see that line there moving through the station”] refers to all those newsreel pictures we’ve seen of the dispossessed moving through the train station—the bag people on the most obvious level, the homeless on the most obvious level, the refugees on the most obvious level—but even those people in apparently more secure or profitable situations who feel that they have not yet arrived at any significant situation.”

Warnes on her A-list cast of players: “Great musicians often become your comrades in the trenches if they have faith that you’re doing something good. If we had been faking it, they wouldn’t have shown up.”

Beck: “A lot of friends were involved in the album. We had a very serious intention for the record, having already worked with Leonard and having so much respect for the music. We wanted to get that across to the people we were working with, too. And they got into it. Everybody did.”

Warnes on Beck: Roscoe’s bass was the backbone of this process. Our first demos and sketches began with bass and voice. If a song ‘flew’ in that sparse setting, additions were easy. One of Roscoe’s great gifts is to make sure that all parts and people are working together. He has an innate sense of rightness, completeness and balance. The crazier it gets, the stronger Roscoe becomes. Every big old ship, and believe me, Famous Blue Raincoat was a very big ship, needs a captain, hopefully one with a heart and some vision. Like George Martin, Roscoe ate, slept and breathed every note. As a result of his dedication, magic did visit us—many times.

Beck on the Stevie Ray Vaughan overdub session for “First We Take Manhattan”: “I arranged for the studio, which was the Record Plant, on very short notice. Tim Boyle was the engineer. But by the time I’d made all the arrangements and got back to Stevie, he’d been asked to do another session with Teena Marie [for her 1986 album, Emerald City], so he asked if we could move ours back a little to allow him to do both. It was a long night. [Laughs] That Teena Marie session, which was at some other studio, went late. Jimmie Vaughan was there hanging out, and Jennifer was there, too. We’d gone down to give Stevie the guitar. I kept calling the Record Plant and moving [our session] later and later. We got to the Record Plant at maybe two or three in the morning. Alexander Dumble [builder of some of Vaughan’s amps] was kind enough to bring an amp to the studio—in pieces, because he didn’t have a whole one—and set it up on the console. I gave Stevie my old Strat and a wah-wah pedal, and he did five takes.”

What was he playing to? “He was hearing Vinnie’s drums and Jennifer’s vocal and when we got to the studio, there was still just a sequenced bass playing eighths. Jennifer said, ‘For God’s sake, at least give him a real bass to play to,’ so I threw a bass part on there—it ended up not being the final part, but was close to it. When we walked out, the sun was up.” Warnes: “At the end, Stevie said, ‘OK, Roscoe, you put it together,” and he left, and Roscoe edited it [later] from the takes we had.”

Beck on the creative use of reverbs in the mix at Amigo Studios: “You’d have to ask [principal mixer] Frank Wolf to be sure, but I think the Lexicon 224 was at the mix, and an EMT 250. I’m certain we used an Eventide delay and I believe Amigo Studios also had a nice plate. Some of the delays on Gary Chang’s keyboard parts might have been printed to digital tape when we recorded them, as the delays were essential to the construct of his keyboard parts.

“The album was mixed to half-inch analog tape, at the very end of the project to give it warmth. So despite the fact that the first CD’s were issued with a ‘DDD’ marking, it was actually ‘DAD.’ In a blindfold test in Amigo Studio B, Frank Wolf, Jennifer, Henry Lewy, and myself, all chose half-inch analog tape over every digital mix format available that we could test—the Sony 1610, Sony 1630, and a Mitsubishi X-80 2-track digital recorder that used ¼-inch tape.”

Warnes: “For the new vinyl release on Impex Records due out this year, Bernie Grundman mastered directly from the original 1986 analog reels.”

Did the song arrangements change much over time?

Warnes: “Every track was pretty much as you hear it. We didn’t have to come back and do a song twice in another style. We had played with Leonard for several tours, and I had been with him back when I was 22 and did other tours, so the music was very familiar. What was really important was the arrangements. [Beck and I] planned it all ahead of time. We sketched every song out at Roscoe’s house. We got the keys and tempos and then we sent out cassettes to [the musicians] that gave them the general gist, and then [keyboardist and arranger] Bill Ginn showed up with paper and made sure all the notes were correct.

“It was like a real good baseball team, where everyone adds something special. Without George [Massenburg] we wouldn’t have that record. Without Billy [Youdelman] we couldn’t have done what we did. And Bernie Grundman’s superb mastering made the final product take on a bright shine. If you remove any one element—like Stevie’s guitar, or any one of the songs—it might not have flown. Every person on it was important, and everybody loved each other and everybody loved Leonard.”