Jackson Browne wrote “The Birds of St. Marks,” the song that kicks off his superb new album, Standing in the Breach, when he was just 18, living in New York and penning wise-beyond-his-years songs that would be recorded by such diverse artists as Tom Rush, The Byrds and Nico—years before his self-titled Asylum Records debut made him a rising star in 1972, when “Doctor My Eyes” became a surprise Top 10 hit. That album was the first of five straight indisputably great records Browne cut in the 1970s, establishing him as one of the most poetic, perceptive and emotionally attuned singer-songwriters of the modern era. [The other four are For Everyman (1973), Late for the Sky (1974), The Pretender (1976) and Running on Empty (1977)]. He also found time to produce his friend Warren Zevon’s fantastic first two albums, Warren Zevon (1976) and Excitable Boy (1978). Browne’s growing popularity through the first half of the ’80s, when he landed a handful of singles in the Top 40, showed that he had a definite mainstream knack, too.

Not all of his fans embraced his move into the overt political commentary and social consciousness expressed on late-’80s albums such as Lives in the Balance and World in Motion, though that development was hardly a surprise—for many years he’d given his time to dozens of good causes, big and small. Indeed, there are few artists who have played more benefit concerts than Jackson Browne. With the exception of his extraordinary, deeply personal 1993 record, I’m Alive, his albums have continued to mix songs that reflect the tumult of the world we live in with engaging meditations on matters of the heart and soul—classic Jackson Browne terrain.

World in Motion was the first of Browne’s albums to be recorded at his own Groove Masters studio in Santa Monica; Lawyers in Love and Lives in the Balance were recorded at Jackson’s previously owned studio, called Downtown, in Los Angeles. His earlier records were cut at a variety of top L.A. studios, such as Sunset Sound, Elektra, Hollywood Sound, Sound Factory, Record One and The Complex.

Through the years, he’s worked with scads of fantastic engineers and mixers, including Richard Orshoff, Al Schmitt, John Haeny, Greg Ladanyi, James Geddes, David Tickle, Ed Cherney, Bob Clearmountain and, on all his albums since I’m Alive, Paul Dieter, who both engineered and co-produced Standing in the Breach at Groove Masters. The list of musicians and singers who have contributed to Browne’s albums must easily number more than 100, including A-list pals ranging from various Eagles and Little Feat members, to Linda Ronstadt, Bonnie Raitt, David Crosby, Graham Nash and Joni Mitchell; and an amazing assortment from the crème de la crème of L.A. players: guitarist David Lindley (his main foil for many years), the versatile backing group known as The Section (guitarist Danny Kortchmar, bassist Lee Sklar, drummer Russ Kunkel and keyboardist Craig Doerge), drummers Larry Zack and Mauricio Lewak, bassist Bob Glaub, guitarists Waddy Wachtel, Scott Thurston and Mark Goldenberg, bassist Kevin McCormick and dozens more. As I joked during our interview, “It takes a village to make a Jackson Browne record.”

In keeping with that ethos, Standing in the Breach features half a dozen different bassists and drummers and several different keyboardists, but the core sound comes from three players—Browne, guitarist Val McCallum and master-of-all-guitars Greg Leisz. (Those two are part of Browne’s current touring band, which also includes bassist Glaub, drummer Lewak and keyboardist Jeff Young). The album’s 10 tracks cover a range of musical styles, yet never depart too far from Jackson Browne territory.

In its modern incarnation, “The Birds of St. Marks” sounds like a long-lost Byrds track. “Leaving Winslow” is a shuffling, countrified train song. “If I Could Be Anywhere” starts with a Beatles-ish bounce and ends with a dreamy instrumental ride-out. “Walls and Doors” was written by the popular Cuban musician Carlos Varela, and features some of his band. Browne and Rob Wasserman wrote the music for “You Know the Night” to unpublished lyrics by Woody Guthrie. And “Yeah Yeah” is a classic Jackson Browne relationship song with an irresistible hook. The arrangements are tasteful throughout and the sonics impeccable; the music breathes and feels alive. If you haven’t checked Jackson Browne out for a while, this album is a good opportunity to get reacquainted with him.

In late August, I spoke with Jackson by phone from Connecticut, where he was playing a solo gig. We talked about the making of Standing in the Breach, more generally about how he likes to record, and also a few other topics.

You’ve been coming out with studio albums only sporadically in recent years. When does it become “album time” for you?

Well, it’s a blurry line because I have a studio and I sometimes cut songs way before I have enough songs for an album. So I’m sort of always recording. I think I once read about Paul Simon that he would cut songs as soon as he wrote them and then he’d write another one and cut that, and I sort of envied that. I never liked the approach where you cut all the tracks and then you sing all the tracks and then allot this amount of time for overdubbing. I guess that’s a cost-effective way of making a record, but that makes it too much like an assembly line. So what I do is have a gradual accumulation of songs I’m working on.

And some of the songs on this album were cut quite a long time ago. For example, “If I Could Be Anywhere” must have been recorded more than a year-and-a-half ago. Were they all recorded at your studio?

All except for one song, the last one on the album, “Here.” That was also cut awhile back. It was recorded at Berkeley Street Studio in Santa Monica because mine was rented out! I had written it for the movie Shrink. I wrote it on the road and came back to town and had to cut it quickly, because they needed it right away. But it was never quite the record I thought it could be.

This album reminds me a little of that Richard Linklater movie, Boyhood, which was shot over a period of years, because some of these songs were written a long time ago. Like the “The Birds of St. Marks” is a song I wrote when I was 18, but I never got to do it like I thought it should be done in the beginning. I remember writing the song and thinking, “This would sound good as a Byrds song.” But it never seemed finished, and after a while I sort of forgot about it. I didn’t even remember it when I was pitching songs to The Byrds sometime after my first album. Years later, I rediscovered the song during an interview for the long-form video Going Home.

The piano version you recorded on Live Acoustic Vol. 1 [2005] is so different than the one on the new album, though it certainly feels like a Jackson Browne song in the classic sense.

There was a way in which the chords went that made sense on the piano, but on just the guitar [back when I wrote it], while it made sense, it didn’t sound full enough, and it would have taken the 12-string and the bass and the drums to get it how I heard it.

Jeffrey Young, Jackson Browne, Bob Glaub, Mauricio Lewak, Greg Leisz, Val McCallum

Photo: Nels Israelson

Greg Leisz, who’s one of my favorite guitarists, sounds great on the 12-string on that.

He’s the reason I thought of doing “The Birds of St. Marks”—because I knew he was a good 12-string player. He played 12-string on my song “The Naked Ride Home” [from the 2002 album of the same name], and working with him was such an eye-opening experience. He was able to go so deep into the groove of the song and find these parts that made the whole song sort of pulse and vibrate in an essential way. Normally when you overdub you’re adding something, and you hope that it’s not something superfluous. But with him, he goes right to the center of the thing; he grabs it by the spine. So I showed him “The Birds of St. Marks” and asked him if he wanted to cut it like a Byrds song with the 12-string, and the idea intrigued him. So that was the beginning of his working on this album. Then I started thinking of other songs he might fit on, and Val [McCallum] is a huge fan of Greg’s, and vice-versa, so the more we got to do, the more we wanted to do, and they wound up playing together on eight songs and are each on one of the songs alone.

So, is the way that a lot of these tracks came together a matter of whoever was around when you decided you would go in and cut a given song? I count six different bass players, six different drummers, but then I looked back at the credits for your older albums and it became clear you’ve always worked this way, with a couple of exceptions.

I did decide after the last record [2008’s Time the Conqueror, cut with his band at that time] that I would go about each song separately and call whoever seemed right for that song. So it wasn’t “whoever was around,” although there was a little of that. I think I used [bassist] Kevin McCormick less and Bob Glaub more because Kevin was out for most of the last couple of years with CSN.

Bob Glaub’s been a dependable presence for you over the years.

Yeah, he has. You know, Bob’s not credited as playing bass on “The Pretender,” though he played on that song. Somehow, the credits were wrong on the original release, and then, when it was re-released again on [The Very Best of Jackson Browne] they got it wrong again! I know he played that part, and it’s so like his playing. But somehow, when we were doing credits, Lee Sklar got credited. [Laughs] Anyway, Bob has played on some of my favorite records, and he and I have been good friends all this time. And Bob and Kevin are really good friends, too.

So it’s about: Who do you call for this specific thing? Like, I got [drummer] Don Heffington to play on a couple of songs. He was the drummer with Lone Justice and has played with so many great people. He’s a great drummer. I actually got to play with him at an Adam Sandler Christmas party once. There were three drummers there who rotated in and out of percussion and drums, and they did this heroic 40-song set, just playing one song after another and I got to play with him there. And I knew him from the Largo [club], too. He plays with Sara and Sean Watkins a lot. He also has an amazing record out now called Gloryland.

My whole album was influenced by these sit-ins and get-togethers at people’s houses and at various friends’ gigs, like Val McCallum’s.

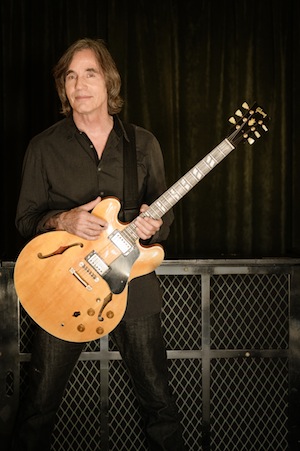

Jackson Browne performing live in 2012.

Photo: Steve Jennings

Isn’t he also part of some loose band called Jackshit, or something?

He is. I sit in with Jackshit sometimes. It’s in that spirit where you’re just having fun playing songs, and I wanted to have that feeling for this record—where I’d call people and we’d have fun recording, and there was less emphasis on cutting the definitive version. I mean, you always try to make the best recording of a song you can…

“If I Could Be Anywhere” I cut with Jim Keltner on drums and Tal Wilkenfeld playing bass and [Heartbreakers keyboardist] Benmont Tench. It’s a song I had tried cutting before, but it didn’t have the urgency I thought it needed. So I thought, “I’m going to cut this more like The Beatles—bomp, bomp, bomp, bomp—and I asked Benmont to play 4s on the piano, but even then it wasn’t quite right. That song didn’t come easy. But Keltner, who never really plays anything the same way twice in a row, wound up coming up with that feeling of urgency the song needed to deliver by simply playing 4s straight through the song, and then, spontaneously, he and Benmont played this incredible ending, which I never could figure out how to cut down, so we left it all in.

You’re a jam band!

[Laughs] Not exactly. But I like the fact that the three songs that actually try to have something to say [socially/politically]—in the case of “If I Could Be Anywhere,” about the state of the ocean and about Empire; there’s a lot to chew on—have long ride-outs. “The Long Way Around” is another one. It goes on for a while and you’re left listening and hopefully thinking a little bit. It gives you a little time before the next song starts.

I really like the amount of space your engineer, Paul Dieter, leaves in the music. There’s plenty of room for those vibe-y, atmospheric guitars that Val McCallum seems to specialize in, and also enough air around your lead vocal.

Paul is great. He’s is also my front-of-house mixer and really winds up listening to everything I do, so he’s used to reaching for the vocal and trying to make the vocal heard. That’s something he brought to this album. He’s also really good at balancing things quickly, and he knows there’s this version, and the next version, and there will be the next version after that. [Laughs.]

How do you know when you’re done?

You run out of money. [Laughs] You need to release something. For me, it’s like a two-cylinder engine, where you tour for a while, and you go home and record for a while, and then you tour some more. But because we’ve made records of the tours, too, it gets pretty blurry. I guess there comes a certain point where you begin counting up the songs and you think, “Oh, we’re close to having enough songs for an album.”

I think the album is plenty long enough, and you could make the argument that a couple of these songs could’ve had less-long ride-outs; you could have some shorter songs. But all these songs are long, in and of themselves—there are a lot of lyrics. So you have to make it so people can hear them. I have made records with songs that have too many words and they go by so quickly you can’t really hear them. Like the original version of “In the Shape of a Heart” [on Lives in the Balance] is not the best recording of the song, because there’s too much going on to really hear the lyrics. When I would just play that song for people by itself they would say, “When did you write that? Is that a new song?” [Laughs] And that’s with them having heard the old one! The words just hadn’t registered with them. So I realized I needed to make records that made you want to listen, and where you can really hear everything.

You had a period where you used some different mixers—David Tickle, one with Ed Cherney, another with Bob Clearmountain. I’m wondering what having that added viewpoint does for you, because you obviously have a pretty firm idea of what you’re after.

I did that for a long time and it was because I couldn’t really see sitting there for a year with any of those guys taking up their time. [Laughs] But I wanted to work with them. What it provides is a break in the making of the record, where someone else comes in and turns it into something slightly different. I would look at Cherney [who mixed I’m Alive] and say, “Really? This is what it sounds like?” And he would say, “Yes, this is what it sounds like. That’s it.” The thing is, you hear it all kinds of different ways before its finished—especially when you’re overdubbing, you tend to listen to things out of proportion.

That didn’t used to happen with Greg Ladanyi. I used to make whole records with Greg Ladanyi [Zevon’s Excitable Boy, Running on Empty, Hold Out, Lawyers in Love] and that was a way of working I have missed in recent years—the same guy who recorded it, would mix it. So I feel this new record is a little more like that. It was a really conscious attempt to see whether Paul and I would hear it the way we’d been hearing it throughout the process and pull it together and deal with balancing it—can you get the best of everything you’ve heard as you’ve been working?

Sometimes it works to give it to somebody else and have them put it together at the end, too, but there’s kind of no going back. It’s very difficult to say, “Well, there was this other thing I heard before and I want to go back and listen to this other thing.” Although Bob [Clearmountain] was really good about that. My co-producer Kevin McCormick and I might say to Bob, “Actually, we were thinking something more like this” and I’d get him to change one or two things, and he’d say, “Oh, you mean like this?” and in four motions—whap!—there it would be. And was usually about balances. That was very fulfilling.

Jackson Browne circa 1982 with his Studer A80 at his studio Downtown.

And Cherney has got his own magical thing that happens. One time, I found him out on the corner outside the studio and I said, “What are you doing out here, Ed?” And he said, “Um, I’m just out here waiting for Jesus to get through with the snare drum…” [Laughs.]

What made you decide to have your own studio, like Groove Masters, in the first place?

Well, at one point I had a studio in downtown L.A. [known as Downtown], on the fifth floor of a building on Broadway. I think the idea came from an article I’d read where the Heartbreakers talked about how they made their first album by buying machines and recording in a storefront. I read that and I thought, “Oh my god, you can do that? I’m doin’ that!” [Laughs] So I bought this gear and with a lot of help embarked on what has become a long quest. Before that I had looked into buying Dave Hassinger’s studio on Selma, the Sound Factory. My business people kept saying, “You’d be saving a lot of money and making a great move if you had your own studio to work in.” I was making all these albums back-to-back. So there was that thought in the air. After Downtown, I put the studio in my house—that was called Outpost—and made a couple of records there, but being in my house made it hard for other people to use it. Then, when I got rid of that house, I moved to Santa Monica and built Groove Masters.

Does the way you work require that an engineer be on-call, or do you know enough to get your thoughts down on your own?

I don’t know anything; I know nothing. [Laughs] I can’t do even the simplest things. I have to have an engineer. I’ve got two second engineers—which as you know is the most demanding work in the studio—both of whom are very capable first engineers and able to record and do whatever I need to do. [Assistants on Standing in the Breach were Bil Lane and Rich Tosi.] They can help me with whatever needs to be done, knowing that chances are we’re going to re-cut it at some point. So, it’s sort of like making sketches in a way.

Has Pro Tools made that process easier, in the sense that you can just record and record and record and then edit easily?

Pro Tools has been indispensable. Because I always did a lot of editing—cutting things together or flying things around. We got into Nuendo before Pro Tools, which Paul actually found a little more edit-friendly, and it also had 96kHz/24-bit earlier than Pro Tools did. Pro Tools has become the standard of the industry, and if you have a studio you pretty much need to have it. But, I track on 2-inch tape and then move it to Pro Tools.

I know you made your early records at places like Sunset Sound and Sound Factory—classic rooms. Did you have the same approach to building songs and recording you use today? How did you learn about working in the studio?

I used to follow other producers to a studio, or work with the engineers they had worked with, because I knew I didn’t know anything. Like, I followed Peter Asher around for a while. There was also a guy named Michael James Jackson, a producer, who would suggest players. He would tell me, “You want a great bass player? Call Wilton Felder.” And that sort of thing was very helpful to me. So you try different people.

You worked with Al Schmitt early on, and John Haeny was a great engineer, too.

John Haeny was maybe my first real mentor in the studio. He really taught me a lot. He recorded For Everyman; he did all the tracks and all of the overdubs. He also recorded and mixed Warren Zevon’s first album, Warren Zevon. John was a great recordist and the go-to guy for a lot of people back then. He was also great at balancing things and had a sort of in-born sense of composition. But when it came time to mix For Everyman, we couldn’t really agree on some things, so after finishing it with him, I decided to go in and finish it again, and I did some of the things I wanted to do that he didn’t want to do. I called Al Schmitt to mix the album that Haeny had recorded, and then Al did the entire next album, Late for the Sky. That one was done in a pretty quick time frame.

Did “The Section” band come about organically through them playing on so many different projects together?

Yes. Russ Kunkel and Lee Sklar were James Taylor’s rhythm section, and I was using them on my first album. Lee had met Craig Doerge playing on a Mimi Fariña and Tom Jans session and told me about him, so I hired him. Along with Danny Kortchmar they became “The Section,” cutting their own albums. But they were actually The Section on many albums that were cut in those days.

For a while I would call them for sessions, but I couldn’t afford to take them on the road until after The Pretender did really well and I started to play arenas and sheds. And I paid them every way you could pay ’em! [Laughs] I paid them as an opening act—they opened the show, which gave them the chance to get all dialed in and totally comfortable onstage. I also paid them as sidemen—as my band—and I also paid them as producers, just to make sure they would actually come out on tour. They were so good in the studio. Songs like “The Fuse” [on The Pretender], or any number of things, had come together because of the way they played as a band. They were like a younger version of the Wrecking Crew. Things got done, they got decided on. They played like they’d been playing together for a lifetime. And now they have.

Tom Walsh (with headphones backstage) and Russell Schmitt at the Studer (Running on Empty tour).

Photo: Joel Bernstein

Running on Empty was a milestone in the way live albums were made. You’ve got songs recorded in hotel rooms and tour buses and rehearsals and onstage. Was it always conceived that way, or was that a notion that came after the fact when you heard what you had?

No, that was the idea from the start. You’ll laugh, because it was pretty hare-brained, but Nakamichi had come out with this really great cassette recorder, and for someone like me it sounded as good as anything! [Laughs] So I said, “Why don’t we record everything? With one of these you can record every single thing that happens and put out everything.” It was big—like half the size of phone book—but obviously really portable. I told Peter Asher what I wanted to do and he said, “Well, that’s a noble idea.” [Laughs] “And you’re going to put out everything the way it is? You’re not going to overdub? You’re not going to fix anything?” He looked at me and said, “Okay, but at least do it on a 2-track [reel-to-reel].” Then, I was talking to the guys at Showco, the touring sound company, and they said, “If you’re going to take a 2-track, we have a Studer 24-track—why don’t you take that? Don’t listen to it; just record everything.” Of course, then we were able to fix and fix.

So we put that [24-track] machine in a room and recorded everything that was being done onstage into the machine without listening back. And we didn’t listen back to most of it until we got back to LA. Actually, we did hire the Record Plant truck to do the hotel recording in Maryland and New Jersey, and Illinois, so at two of these gigs we had that to work with. [At all the shows without the truck] there would be a guy in a back room with the Studer, but no console, and he could only listen to one track at a time—so he’d plug the headphones into track 18 and make sure it wasn’t distorting, and then he’d listen to another one. And Ladanyi would call up on the headset because he’d noticed that Russ [Kunkel] was playing softer, and he’d say to Tom Walsh, the guy at the Studer, “What kind of levels do you have on the kick? Is it +3?” And Tom would say, “Yeah, it’s +3,” and Ladanyi wouldn’t believe him and he’d run back to the room in the middle of the song and look at the meter and say, “That’s not +3!” and he’d crank the input. “That’s +3!” and he’d run back to the front-of-the-house. [Laughs.]

But nobody had ever done a live album like that. Most live albums had been done by recording your show on two different nights, with a truck, so we were innovative in that regard. But the guys in the band—David Lindley especially, but also all the guys in The Section—were such a creative group and all this amazing shit would happen spontaneously that I wanted to capture, and we were able to do that. Now, it’s not hard if you want to do that. We’ve all recorded everything that happens onstage for years now.