When it starts, there’s no mistaking what song it is. Four double-notes, played on what sounds like a synthesizer (actually an organ), in a robotic-like sequence for a few seconds, hanging on for a bit longer, and then the rock ‘n’ roll ride begins on The Who’s “Baba O’Riley.”

The Who had been on tour throughout 1969 and 1970 in support of Pete Townshend’s classic rock opera, Tommy, and by January 1971, he had unveiled what he proposed to be his next “soundtrack-type” project, Lifehouse. He and bassist John Entwistle recorded a few demos in their home studios, and the band debuted a collection of the songs, many of which would end up on Who’s Next, at a show at the Young Vic Theatre in London the following month.

Townshend and the group’s producer, Kit Lambert, had parted ways after Tommy, and a fledgling plan to make the project into a movie stalled. Lambert had, in the meantime, moved to New York, and after the Young Vic show, he called Townshend and suggested that the band come to record the songs at the then-new Record Plant, where they became the first act to use the facility’s Studio One. The tracks—which did not include “Baba O’Riley” —were deemed less than satisfactory.

Townshend, meanwhile, had written to legendary recording producer/engineer Glyn Johns, asking for his help. Johns had recorded The Who’s “My Generation” at IBC Studios, London, in October 1965 for producer Shel Talmy. “I had no idea they’d already gone to New York and made an attempt at recording it with Kit,” Johns tells Mix. “I only found out about that after we finished the album.”

Johns was sent demos of Townshend’s songs on acetate discs, having been recorded to 8-track tape (likely a 3M M23) at his home studio in Twickenham, one of several he had throughout the 60s. “Few people know, Pete is an extraordinary engineer,” Johns says. “He’s extremely competent, all around, which is why I appreciate him as much as I do. He’s not just a genius songwriter and performer, but he’s an incredible engineer.”

OPENING WITH ORGAN

Among the instruments Townshend had on hand was a Lowrey Berkshire Deluxe home electronic organ, an instrument commonplace in family homes at the time. “They had rhythm machines built in, with automatic accompaniment,” says Brian Kehew, The Who’s longtime keyboard tech and Moog’s historian. “It would play a simple bass line; if you held down the C note, all based around C, in time with the drum box.”

In 1971, Townshend found a novel way to make use of the organ, in a powerful rock song he had just written, which was based around a story of a farmer whose son has run off and which drew its title from both Meher Baba, an Indian spiritual master of whom Townshend was a follower, and Terry Riley, whom Kehew describes as “an experimental composer who did a lot of repeating figure music and tape loops, something Pete was experimenting with at the same time.

Its theme of a “teenage wasteland,” Townshend has noted, came from observing the mess left behind by drugged-out teens at the Isle of Wight Festival, where The Who had played in 1969.

Townshend had the Lowrey organ and a synthesizer at hand, though it is the Lowrey alone heard on “Baba.” “So much of what people call ‘synthesizer’ in Who music is not,” Kehew states. “’Won’t Get Fooled Again’ is not really a synthesizer—it’s an organ, this Lowrey, being chopped up through a synthesizer, but it’s basically a stutter.”

The setting Townshend discovered on the Lowrey was called “Marimba Repeat,” which emulated sequencing in a way he had hoped to produce using an ARP 2500 he had just recently received.

“If you just hold the keys down, ‘Marimba Repeat’ does these little figures,” Kehew explains. “It jumps around, articulating the notes you’re holding, as if you’re playing very quickly and doing cool parts, but it does it for you. So it’s not a sequencer, and it’s not a sequence. It was a discovery, accidentally, on Pete’s part that it did these things, and he could use them in a rock song.”

Classic Tracks: Oingo Boingo’s “Just Another Day”

Adds Johns: “He experimented with this piece of equipment and stumbled across the idea of it creating a rhythm—and then he got clever with that. And what he turned it into is just astonishing.”

Townshend recorded the organ to a pair of tracks on his 3M tape machine, in stereo, the Lowrey outputting through a Leslie-like rotating speaker. The song does have an Irish jig feel to it, he notes, particularly with the Irish reel violin part at the end, with the fast section during which that plays. “Think about it,” he says. “How’s Pete going to make an Irish sound with a guitar or a piano? So this little thing the Lowrey creates, which comes across as computerized and synthesized to the rest of us, is not a futuristic thing at all. It just gives that impression.”

Townshend also recorded a demo of “Won’t Get Fooled Again” with the Lowrey, this time feeding the output through an EMS VCS3 synthesizer. “He’s just playing a basic Hammond-style patch on the organ, and the EMS is chopping on/off, on/off, and then filtering darker and brighter, like a Leslie sound,” Kehew explains. “Remember, synthesizers of that era could only make a single note, not chords. The EMS is not making its own sound, but it’s processing, basically turning on and off the volume of the Lowrey signal with a square wave.”

FROM MICK’S PLACE TO OLYMPIC

Recording for Who’s Next began first with two days of tracking in the two-story entrance hall at Stargroves, Mick Jagger’s home. Johns had been recording the Stones there and had mentioned how well it had gone to Townshend, who then suggested they record there using the new Rolling Stones Mobile Unit, which Johns had helped design.

“I’ve often found, when recording in a space that’s not designed for recording, one ends up with some very interesting results,” Johns says. “You can very often turn slightly problematical circumstances into something that’s far more interesting than if you were in the best studio in the world. You end up with something original.”

Johns edited down Townshend’s original “Won’t Get Fooled Again” demo and transferred it to 16-track tape, which he played back to the band in the house, where he could see them via a small camera set up in the hall. The band easily adapted to the edit and performed explosively. “I’d never done anything quite that loud in there before,” Johns recalls. “The Stones were much quieter. My memory of ‘Fooled’ is of being in the truck with my hair parted, and that was with the monitors turned down low!”

By the beginning of April 1971, recording shifted to Johns’ then-home base of Olympic Sound Studios, the famed facility’s second space in the Barnes section of London. Johns describes its cavernous Studio A, built into a former movie theater: “It had a very high ceiling. The floor had a linoleum surface on it, and the walls had pegboard blocks on them—and it was the most flexible room I think I’ve ever worked in. You could get a 60- or 80-piece orchestra in there, or you could do a Jimi Hendrix session, or a solo harpsichord. There was facility to record to picture, with a big screen at the back end of the room and a projection booth above the control room. The very high ceiling was the secret, really, to the sound in there.”

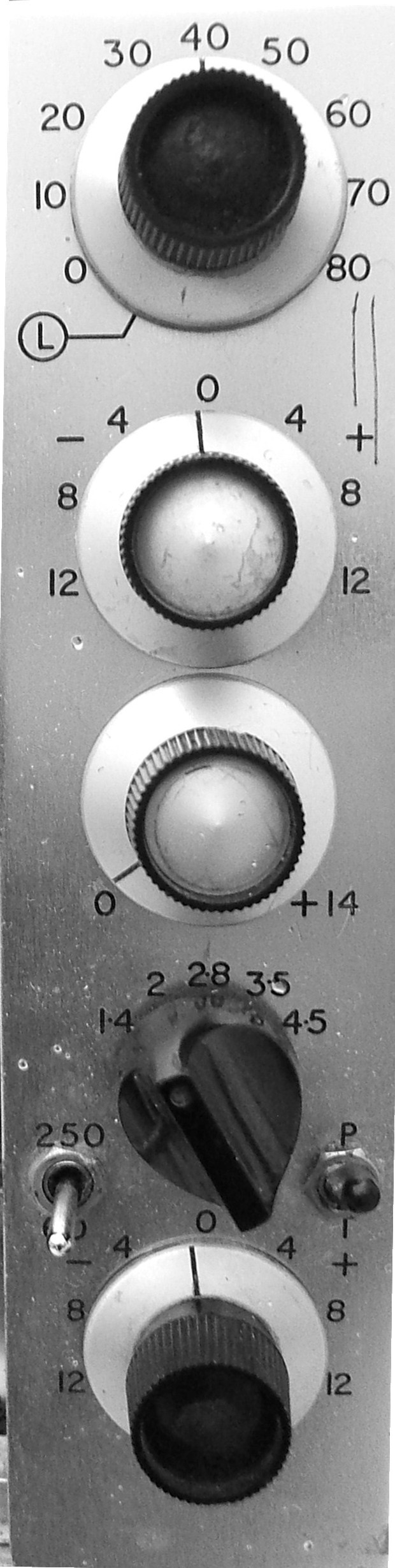

The control room still housed the unique wraparound console built by designer Dick Swettenham, from an idea by studio owner Keith Grant. It had 24 inputs and, at the time, it output to a 3M M56 16-track tape machine. Johns was a fan of the fairly basic EQ modules Swettenham had designed.

“The top knob was just 10k, plus or minus probably 2 or 3 dB steps,” Johns recalls. “Then you could select a middle frequency, and on the low end you could select 60 or 100 Hz, with a little switch, and you could cut or boost in 2 or 3 dB steps. It was that simple, but it was just the inherent sound of the console that was the secret. God knows what that secret was, but it was a magical combination of that console and that room, without any question. You couldn’t really go wrong. You just lift the fader up, and there it was.”

The first step on “Baba O’Riley” — as was the case with “Fooled” — was to copy Townshend’s demo recordings from 8-track to 16. Johns then set the band up the same way he did with every band in that room, whether The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, the Kinks or anyone else. “I set them up in a line, as if they were on stage, facing the control room,” he explains. “It’s comfortable and familiar for them. They’re all very close to each other and within eyesight of each other. People who are playing together subconsciously influence each other. If you record people individually, that doesn’t happen. It can’t happen.”

Miking Townshend’s guitar amp was a simple matter. “It would vary, from one song to the next, and whatever sound he was giving me,” Johns says. “It would probably be a Shure SM57, something as simple as that.” The guitarist didn’t use a small amp for recording all the time, sometimes using his bigger HiWatt, for example. “You’d want to mic that from three feet away, and I’d just use a Neumann U67.” Entwhistle’s bass amp would be miked with an AKG D14, he says.

GLYN JOHNS MICS KEITH MOON

It is Glyn Johns’s signature drum miking technique on “Baba O’Riley” that truly captures the character of Keith Moon’s playing and sound. His basic setup consists of just four mics, and, often, just three: one for the kick drum (an AKG D30), plus two others. “I probably didn’t use the snare drum mic, almost certainly not with him,” Johns recalls. “It was there in case I needed to make the snare especially more crisp, but invariably, I didn’t use it.”

The two main mics, both U67s and both pointing at the snare drum—one overhead pointing down, and the other to the right and above the floor tom—aimed across the kit to the snare.

“They’re equidistant from the snare,” Johns explains. “If you spread those two microphones either side of center, in the stereo mix, the snare drum is in the middle.” The top mic, he notes, with a cardioid pickup pattern, is also live at the top of the capsule, “so it doesn’t just see right and left, but also from the top of the capsule, seeing the cymbals, from above. The mic near the tom tom also picks up a lot of the bass drum sound, as well.

Classic Tracks: The Moody Blues’ “Nights in White Satin”

“My miking technique is designed to try and capture what whoever is giving me is giving me,” he adds. “I want to capture the sound of the individual drummer, and each drummer has his own sound that is peculiar to them. If you mic a drum kit with 10 or 12 mics—if you put a microphone that close to any drum—you’re not capturing the sound of the drum as it was intended, designed. It’s the same for any acoustic instrument. They’re designed for the sound to project into the room, and for the sounds to develop.”

Although a sizable vocal booth was available, Roger Daltrey likely sang his vocal live with the band, into a Neumann U67. His voice, Johns says, was as much an instrument in the band as the other three. “He’d be facing them, and you’d have to have a really directional mic,” Johns says. “He’s very easy to record, and you’d think that with the dynamic of his vocal, he wouldn’t be, but he’s fantastic. You don’t spend hours on a vocal with Roger. He delivers incredibly quickly, and he’s quite extraordinary.”

During takes, Johns fed the playback of Townshend’s Lowrey organ and piano tracks to the bandmembers’ headphones. That was it. No click, even as the track changes pace during the section that would include the later-tracked violin/fiddle overdub by Dave Arbus. “That was Keith Moon’s idea,” Johns recalls. “And he had to speed up with Keith, of course. The rest of the track had already been done, so that was quite difficult to do. He walked it, really. It was really good.”

During takes, Johns fed the playback of Townshend’s Lowrey organ and piano tracks to the bandmembers’ headphones. That was it. No click, even as the track changes pace during the section that would include the later-tracked violin/fiddle overdub by Dave Arbus. “That was Keith Moon’s idea,” Johns recalls. “And he had to speed up with Keith, of course. The rest of the track had already been done, so that was quite difficult to do. He walked it, really. It was really good.”

Johns mixed the album at Olympic on the same console that he recorded on. “For most of my engineering career, I’ve always used pretty much the same setup,” Johns says humbly. “No two EMT plates ever sound the same, and in any complex of studios, if there are two or three, there’s usually one that’s really good that everybody wants and the other two never get used. At Olympic, there was one EMT plate that I really liked, which was very much part of my sound.”

He would also make use of a Revox tape machine, located on the wall at Olympic, which had a varispeed control. “I used that in the send, so there was always a tape delay in the send to the EMT,” Johns says. “I could vary the timing of the delay.”

The recording of Who’s Next, in particular “Baba O’Riley” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” remain in Glyn Johns’ list of his proudest recordings. “Everything about both of those songs was pretty extraordinary. It was, without question, revolutionary in rock and roll.”