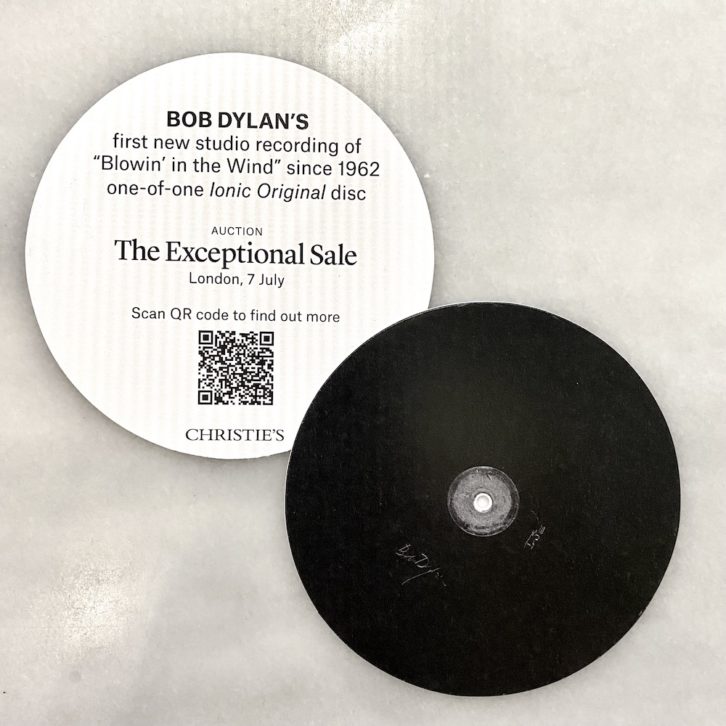

The rising popularity of vinyl may have reached a peak last week when an acetate disc of Bob Dylan performing his song “Blowin’ in the Wind” sold for almost $1.8 million at auction. It makes the $2 million reportedly paid by Martin Shkreli in 2015 for his exclusive copy of the Wu Tang Clan’s Once Upon A Time In Shaolin appear to be quite the bargain. The sale of the Dylan disc simultaneously represents much of what is wrong and right with the popular music industry.

First, a bit of background. The seeds for the Dylan project were sown by Grammy Award–winning music producer T Bone Burnett, who has worked with Dylan, as well as artists including Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, Gregg Allman, Roy Orbison, Brandi Carlile and Elton John. Burnett and his team have developed an analog playback format called Ionic Original, but maybe it should be called Iconic Original.

Exclusive: Inside T Bone Burnett’s High-Tech Reinvention of the Record

For those of you unfamiliar with the vinyl record pressing process (i.e., aren’t as old as I am), it starts with what is referred to as an acetate disc. Technically, the disc isn’t made of acetate; it’s aluminum coated with nitrocellulose (NCL), but the term “acetate” stuck from the discs used years ago.

The master mixes—whether they’re coming from tape or digital files—are cut into the disc using a cutting lathe (a machine that etches analog audio information into the disc). This disc is played back and inspected for flaws, and in Ye Olden Days, the approved “master” would be used to create a number of “stampers,” discs that actually imprint grooves into molten vinyl. Yes, I know, steps are missing, but you get the idea.

The acetate disc is an excellent playback medium and is seldom matched by the quality of the mass-marketed vinyl discs that consumers hear because stampers are not only subject to contamination, they also begin to wear out after a certain number of pressings.

Ask anyone who bought vinyl in the early 1990s, at a time when record companies were riding high on CD sales and abandoning the vinyl format. As a result, they used stampers well past their “use by” date as a means of cutting costs, resulting in some really horrible, noisy, distorted record pressings. Unfortunately, acetate or NCL (or whatevertheheckitis) is not particularly robust, so even if you had an acetate disc of your favorite album, you wouldn’t be able to play it more than a few times.

That’s where Burnett steps in.

In 2014, he and his partners formed NeoFidelity, Inc., and the company recently announced development of Ionic Originals. These one-of-a-kind, archival-quality discs are made using a process that deposits a coating on an NCL disc that reduces friction and enables the discs to be played more than 2,000 times while remaining dead quiet and providing fidelity that vinyl aficionados can only dream of.

Speaking as someone who is sick and tired of hearing crappy MP3s, garbled audio via YouTube and “lossless compression” audio files (there’s an oxymoron for you), I’m also very happy to hear about the Ionic Original format.

It’s just too bad that we’ll never get to hear these discs.

The Dylan disc has set a high bar, one that can only be pole-vaulted by the rich and famous. It marks the first time that Dylan has recorded the song in a studio since the original was released in 1963. The production costs are high, and it will probably take a lot of coaxing and cash to get an established artist to revisit (i.e. re-record) one of their biggest hits, so don’t expect an Ionic Original to come cheap. Burnett, however, has the track record (pardon the pun) to attract A-list artists, get them into the studio and produce a great recording. On the one hand that’s a drag for those of us who have more down-to-earth concerns such as food, shelter and health insurance, and will never be able to afford an Ionic Original. On the other hand, it’s a plus for songwriters and performers because it clearly demonstrates that music can maintain its value in a world that is constantly trying to devalue what we do.