As you probably noticed from the photo that appears most weeks along with this blog, I’m a guitar player. So you won’t be particularly surprised to learn that I record a lot of guitar parts in my home studio. I thought I’d use this week’s blog to share my workflow for electric guitar overdubs, which almost always starts with a DI recording rather than a miked amp. I find it to be quite efficient.

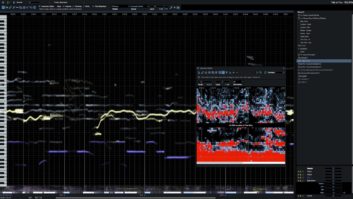

Unless I’m recording a clean rhythm track, I’ll usually track guitar while monitoring through an amp-and-effects modeling plug-in (my current fave is Line 6 Helix Native). I think it’s important to monitor with a similar sound to what I’m going to end up with or I might not be able to play the part with the right feel. It would be odd to record a track calling for a high-gain amp tone and a lot of sustain with a totally clean and plunky DI sound.

Read more Mix Blog Studio: Truly Mobile.

Of course, monitoring through a plug-in brings the latency devil into the equation, but as long as I’m able to set my record buffer at 256 samples or lower, I can deal with it. I’ll bleed a little direct sound in my headphones just to help me stay locked with the time if the latency is making it tough. If I’m working on a song that’s already got a ton of tracks and plug-ins, and it’s using too much CPU power to allow me to set the buffer that low, I’ll make a reference mix and open it in a new session. I’ll track my part along with it, and then import the new guitar track into the original session.

But fear not, purists, this doesn’t mean I use an amp modeler for the final sound every time. I’ll often reamp the DI tone through a tube amp and mike it. But typically I won’t make the final decision about a tone—whether to keep using the modeler or whether to reamp and mike—until I’m well into the mix.

Reamping a DI track is a slightly strange experience. The part you played is coming out of the amp, but you’re just sitting there listening to it—almost like the guitar version of a player piano. I’ve been doing more and more reamping lately, though, because knowing I can do it as late in the process as I want allows me to put off the final tone decision. If I record through an amp from the start, I’m locked into that sound (unless I also record a separate DI feed, of course).

The biggest drawback to reamping, and it’s really more of an inconvenience than a major issue, is that the resultant track needs to be time-aligned with the DI track because it will get slightly delayed going through the electronics of the reamp box and the recording chain.

If, however, I’m playing a session in somebody else’s studio, I prefer to go through an amp or a hardware amp modeler so that the track is printed with my tone. I’d rather not give somebody else the opportunity to radically change my sound when I’m not there. Naturally, when another guitarist records in my studio, I extend him or her that same courtesy.

Guitarists are pretty particular about their tone and don’t generally like the idea of an engineer or producer—who may or may not be a guitar player—mucking about with it after the fact. As they say here in New Jersey, “Fuhgettaboutit!”