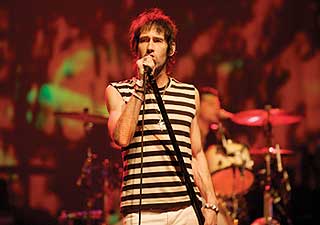

Sam Endicott, lead vocals/guitar/programming

Front-of-house engineer/tour manager Keith Danforth explains The Bravery’s touring strategy simply: Keep things light. After all, this is a band that’s bounced between small and large clubs, amphitheaters and even a stadium or two since its self-titled first album was released in 2005. “On each tour, they will have a cornucopia of different events,” he says. “So carrying a truck full of gear around that we only need half the time doesn’t make much sense. Plus, when you’re globe-hopping, you quickly learn the less you bring the better.”

Danforth and monitor engineer Scott Eisenberg have been with the quintet since the early days. Whereas Danforth got the gig based on his experience at the Viper Room in Los Angeles, Eisenberg first met the band before their eponymous debut was released when they came through a club he was working at in Boston. Despite this experience, Danforth and Eisenberg were adjusting to a collection of songs from the band that hadn’t yet been released. Those songs featured new backing tracks to work with, as well as the addition of a bow to Michael Zakarin’s guitar repertoire and a couple of drums for him to play. “It’s been fun to play with that stuff,” Danforth says. “We’ve been doing this for four years together. Those types of textures and additional instrumentation and a host of other things they have added on this run have brought a lot more to the overall sound and what they are going for.”

Sparse FOH, Racks ‘N’ Stacks

In keeping with their “travel light” mantra, the crew arrived at The Warfield in San Francisco in early November with a monitor desk, personal monitors and Danforth’s FOH rack that goes with him everywhere to ensure continuity in singer Sam Endicott’s tracks. The rack is stocked with an Eventide H3000, TC Electronics 2290, and a couple of M1s and D2s.

Front-of-house engineer/tour manager Keith Danforth at the Warfield’s Midas H3000

“The H3000 and 2290 are pretty high-end, but the M1s and D2s are there because they only cost a couple hundred bucks, so if they destroy themselves it’s easy to grab another one and I’m not in the middle of nowhere looking for vintage gear on a Wednesday,” Danforth explains. “I try to keep most of what I’m doing as simple as possible so that it doesn’t become a big complicated mess moving from venue to venue and situation to situation every day.”

The console at The Warfield is a Midas H3000 and the P.A. includes 22 boxes of Meyer MILO gear, 11 HP-700 subs, a pair of MSL-4s and four CQ-1s for front-fills and six M1Ds for under-balcony fills. Most of the time Danforth is fine with what’s at the venue. “I care that it’s a name brand and there’s a bunch of it,” he says of the P.A. “In general, I would like to see something that has a little more power and a few extra boxes so that I don’t have to turn it up so loud.

“I listen from the FOH position — mixing for the bulk of the room — and then walk around to see what changes may need to be made to fill things out, to create an even feel in the venue,” he continues. “I’m not going to grab a tablet and sit in every seat in the balcony. But I will walk the room during soundcheck and make sure there is continuity. That’s all you can do unless it’s your P.A. anyway.”

Monitor engineer Scott Eisenberg at the Crest HP-8

The only other thing Danforth carries is a mic package that includes a collection of Shure 57s and 58s that are used on vocals, snares and guitars, as well as a couple of Sennheiser tom mics and a few KSM 32s that are also put on guitars. “I like to get a condenser and dynamic working together so we get the meat and potatoes out of one and nuance and volume out of the other,” he explains.

Endicott sings into a 58, for their durability if nothing else. “Sam has a habit of throwing them up in the air and not catching them,” Danforth says with a laugh. “We get boxes of grilles sent out to us on a regular basis for that reason. We just want to make sure he doesn’t cut his lip on the busted grille; the mic itself sounds fine the whole time. They are road warriors, and we love them.”

While Danforth is not a fan of an effected vocal track, he’s been charged with replicating the sound the band used during the recording of the most recent collection of songs, as well as their past catalog. He specifically mentions the song “Slow Poison” off the new album, Stir the Blood (released last November), as an example. “It has a very distinct delay on it that we use live to create the same vocal effect,” he says. “Another song has flange on it and we do the same thing for that. Those are pretty album-specific and most of it translates live. It’s not the same thing that’s on the album, but it has the same desired effect overall.”

Laughing, he says that he won’t divulge the exact processing used on Endicott’s vocals, but he does admit there are effects on every song. “You have to have a decent reverb on it so the vocal sounds nice and even,” he says. “A lot of times I’ll use a chorus on the vocal, but I will use the Eventide program that has a zero-percentile shift that doesn’t move the note necessarily. Sam’s on-key enough that I don’t necessarily need to use it to make it sound like he’s on; it’s really just to beef up the vocal to get it over the sheer volume of the rest of the band.”

Overcoming Stage Volume

That said, as most of the band has moved to personal monitors (Sennheiser 300s), Danforth’s challenge to get over the band is not as difficult as it once was. In fact, the only person still on wedges is bass player Mike Hindert. “When we started out, they were all on wedges and it was really loud onstage,” says Eisenberg. “Anthony [Burulcich], the drummer, is solid, but not a heavy hitter, and the guitar player isn’t insanely loud, but just because of the monitor volume, the vocals had to be super-loud and then everybody was competing.

“Going to in-ears quieted the volume,” he continues, “and dropping the side-fills and the wedges for the drummer helped, and the singer felt much more comfortable. But, it’s interesting, because no matter how quiet it is onstage, you still have to deal with front of house and every once in a while there’s that one night where you’re in a club and the subs are kicking, and Sam’s like, ‘Can we turn down the bass?’ There’s nothing I can do.”

On the band’s headlining dates, Eisenberg works on a Crest Audio HP-Eight console that they own. “If we’re opening for somebody like Linkin Park or Green Day, we’ll use what they have,” Eisenberg adds. To get the wedge mix at the Warfield, Eisenberg sent a mix from the HP-Eight into the venue’s PM5D to use that board’s EQ.

So far, he is not carrying outboard gear for monitors. “Every now and then, the band will ask for a little bit of reverb, but usually the mixes are pretty focused,” he explains. “Every so often, I’ll use some compression, but unless it’s absolutely necessary, I won’t use a gate. If the drummer hears [a gate], he’ll start playing lightly, and then say, ‘Hey, how come I can’t hear that?’ Even with compression I’ll go pretty light because it seems like they want exactly what they are doing instead of a processed sound of it.”

Mixes across the band are fairly standard, with everyone getting a bit more of their instrument in addition to a general mix, except for Endicott, who gets mostly his guitar and vocals. The drummer can adjust his own ears, including the amount of click he’ll hear on any given song via a mixer installed at his kit.

As the band’s stature has grown and they begin to play on larger stages, Eisenberg has been asked to provide different things to their mixes. “On the biggest stages they want to hear what everyone else is doing,” he says. “On the smaller stages they’re asking for more audience. I’m just guessing, but I think that’s because when they’re the headliner, the crowd is there for them and there’s more enthusiasm and they want to be in on that.”

David John Farinella is a San Francisco-based writer.