If you’re reading Mix, you likely owe your livelihood to your ears. Well, here’s a question: When was the last time you had your hearing tested?

For nearly 40 years, audiologist Dr. Michael Santucci, president of customized hearing protection specialist Sensaphonics and ASI Audio in Chicago, has been on a mission to protect musicians—and engineers—from the damaging effects of loud sound. A musician from a family of musicians, Santucci was inspired to found Sensaphonics in 1985, initially researching and evaluating ear-filtering products, after the singer quit the band that he was in because her ears were ringing.

“I am all about safety, being an audiologist,” he says.

He developed his first custom product for famed voice-over artist and “word jazz” exponent Ken Nordine. The Grateful Dead’s engineers were recording Nordine’s performance and asked if Santucci could make some ear monitors for the band. “That put me on the map—and then I got referrals to Aerosmith and Poison, and I really got into this thing,” he says.

If you are an audio professional, in the studio or in performance sound, Santucci has a recommendation: “Get an annual hearing test.” That way, he says, you and your audiologist can track changes over time and make informed decisions about your career and the way that you work, such as monitoring at lower levels or spending less time listening.

Your hearing is not only critical for your job, but also for brain function. It’s complicated, but as neurologists have discovered, there is a link between cognitive abilities and hearing, both for better and for worse. Working as a musician has been found to “foster cognitive strengths such as attention, working memory and creativity,” as Nina Kraus notes in her 2021 book, Of Sound Mind. (Such acuity is shared, she writes, with athletes and those speaking two or more languages.)

Conversely, hearing loss can be an accelerant for dementia. “Google ‘untreated hearing loss and early cognitive decline’ and see how many thousands of studies come up showing that it’s the number-one causal relationship,” Santucci suggests.

LISTENING AT SAFE LEVELS

The best way to protect your hearing is to monitor at a safe level. Film and TV post-production engineers typically mix to standardized reference levels, while engineers working in music production can follow those recommendations or not, as they wish. In live sound, all bets are off, especially if the screaming crowd overpowers the P.A.

So what exactly is a safe listening level? That, too, is complicated, and subject to evolving science.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration established legal requirements for U.S. workplaces in 1981 that limit exposure to noise. “If you’re at 90 dB, A-weighted, you can be in it for up to eight hours,” explains Santucci, who is a core member of the World Health Organization’s Make Listening Safe Initiative and established a Hearing and Hearing Loss Prevention Technical Committee with the AES in 2005.

“If you’re in over eight hours, you’ve got to wear hearing protection,” he adds. “Every time you go 5 dB louder, you must cut your exposure time in half, so at 95 dB, it’s four hours; at 100 dB, it’s two hours; and so on.”

However, those rules are for industrial settings, he points out, and only about 5 percent of workplaces are even at 95 dB or above. Few sound engineers, if any, are working a 40-hour workweek at that level continuously. Live sound engineers are generally well above 95 dB, but only for a two-hour show (plus soundcheck, of course).

Even with those rules in place, about 28 percent of people have still lost some hearing, Santucci reports, but alternately, “that means 72 percent have maintained their hearing, so that’s good.”

Enter OSHA’s scientific branch, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. “NIOSH said 3 dB is twice the intensity, and we’ve seen hearing loss at 85 dB, so we’re starting at 85 dB, and every time it goes up 3 dB, you have to cut your time in half. By the time we get to 100 dB, one scale says two hours and the other one says 15 minutes,” he observes. “Which one is the right one? I don’t know. We know that those safety criteria work, but I think that sometimes they’re overkill for music. However, being a scientist and a hearing-loss prevention doctor, I’ve got to go with the science.”

PUTTING IT IN PRACTICE

To help manage your exposure, Santucci says, NIOSH offers a free, Apple-only sound level meter app: “You download it, you put the NIOSH app up and it says you’re this loud and you’ve reached your dose.”

Santucci is also about to release a handheld device, dB Check Pro, that can be inserted into the wired headphone path and includes presets for the major brands and models. “You dial in your headphones, hit Play, and it’ll start telling you how many dB you’re listening to. Then it converts that to allowable time in minutes for both OSHA and NIOSH,” he says. It can simultaneously meter a room mic on either scale.

ASI Audio 3DME BT G2 Active Ambient In-Ear Monitoring – A Real-World Review

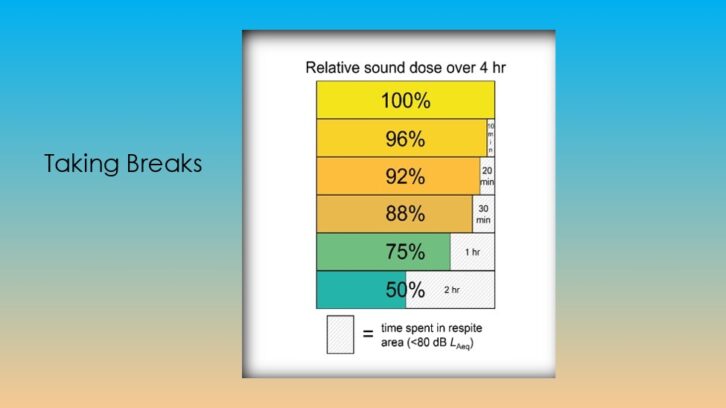

One way to extend your allowable exposure time is to take breaks. “I have a chart that shows the amount of reduction in dosage with taking a 20-minute break, a half-hour break and so on.” he says. “That means you can listen a lot longer.”

Arguably, most musicians are better protected than their engineers, who typically don’t wear headphones full-time in the studio or during live shows—other than monitor engineers, who frequently wear IEMs these days. That said, musicians playing in traditionally unamplified settings, such as classical music performances, may have endured years of excessive exposure, as have those rock musicians who tend to pull one ear monitor out. Santucci has a solution for that, too, through the ASI Audio x Sensaphonics brand of 3DME (Three-Dimensional Music Enhancement) products.

PROTECTION ON STAGE

ASI’s app-controlled 3DME body pack enables musicians to independently balance between the mics embedded in the earpieces and, in amplified settings, the feed from the monitor engineer. That solves the problem for rockers who miss the onstage ambiance and, in unamplified situations, enables musicians to attenuate nearby louder colleagues—or discreetly correct for their own hearing loss.

Wait, is classical music really that loud? In 2012, a professional UK musician sued after suffering career-ending hearing damage because the brass section that sat behind him generated levels of over 135 dB. Compare that to metal band Manowar’s reading of 129.5 dB in 1984, which was the Guinness Book of World Records’ loudest performance until the category was, for obvious reasons, discontinued.

PHOTO – RICHARD TERMINE

No surprise, then, that ASI has furnished New York’s Metropolitan Opera Orchestra with 3DME systems. “If you’re a violinist and you want to protect your hearing, you set the limit,” Santucci explains. “Perhaps then your violin doesn’t sound right, so you have seven bands of EQ, but you can also amplify up to 12 dB, in analog. When I do demos for orchestras, I get at least four or five people, and the tears start coming down. They can correct their own hearing loss on their phone. Nobody knows, but suddenly they’re playing better.”