Finding the right producer can be as important, and sometimes as difficult, as finding the right bandmembers. The right producer came to the hard rock group Staind on his own. Producer/engineer/musician Josh Abraham — who recently launched his own label, JAB Records, and whose credits include heavyweight acts such as Limp Bizkit, Orgy and Korn — shares management (The Firm) with the Massachusetts-based group and, “looking to get into a more organic field of production,” he asked the company to set up a meeting with vocalist Aaron Lewis, guitarist Mike Mushok, bassist Johnny April and drummer Jon Wysocki. What he didn’t expect was just how organic their collaboration, Break the Cycle — which entered the charts at Number One this past June — would be.

“To be honest, I thought I was going in to make the heavy follow-up to Dysfunction [Staind’s successful 1999 major-label debut],” says Abraham, who instead found himself producing and engineering a more melodic, acoustic-based album. “The first time I heard Aaron sing ‘Outside’ was on the way to a rehearsal. I didn’t even know the song existed. Up until that time, I thought he was just a screamer. I asked him to play me some demos, and ‘It’s Been Awhile’ [the CD’s first single] was a song that he’d written five or six years ago. I said, ‘This is great stuff! Let’s focus on your vocal performance.’”

What might surprise Staind fans, who immediately bonded with Dysfunction‘s aggressively delivered, heart-on-sleeve lyrics, is that Lewis was a self-described “choir geek” who sang in the All State Choir while in high school, performing such classics as Schubert’s Mass in G. Prior to Staind, he performed acoustically, playing guitar and singing Cat Stevens, James Taylor, and Crosby, Stills & Nash songs. Those roots, however, are not far removed from those of his bandmates.

Mushok, who studied guitar under Tony MacAlpine, shares Lewis’ passion for melody and poignant lyrics, citing James Taylor, Jim Croce and the folk music his parents loved as his musical foundation. Break the Cycle isn’t the stretch that one might imagine.

“We aimed to make this record different from the last one,” Mushok says. “We wanted to accomplish the melodic elements, and it was difficult for me, because there were days when I literally paced around my backyard thinking my head was going to explode because I would have four song ideas going on at once. I’d listen to the recordings and wonder, ‘Is this any good?’ I lost my perception a bunch of times because I was so close and wrapped up in it. I had to step back and take weekends off to come back with fresh ears and try to pick out what was good and what wasn’t. So in writing the songs, for me there was a lot of doubt and trying to push myself to get rid of that doubt. It was hard as we went along, but we finished it two days before Christmas, I went home with the rough mixes and at that point I was able to say, ‘This is really good.’”

Unlike so many rock bands who track in one place over a matter of weeks, Staind changed studios several times. “We recorded in four locations,” says Abraham. “The bulk of the record was done at NRG Studios in North Hollywood. We spent six weeks recording drums, bass and guitars, then we resumed work on vocals at Longview Farm Studio in North Brookfield, Mass. We tracked the song ‘Pressure’ in its entirety at Electric Lady in New York. We finished vocals and did the last touch-ups at South Beach Studio in Miami. Each setting created a new vibe. If we’d get stuck from staying in one place too long, we’d go somewhere else and think things out in a different way.

“I do all vocals on Pro Tools, so it’s not hard to keep the continuity,” Abraham continues. “You just pack up, take your drive, plug it in and roll. We’d start from scratch on a song, vocally, so there was nothing to punch in or overdub. Pro Tools is a big part of what I do. I’ve been using it since it was Sound Tools.

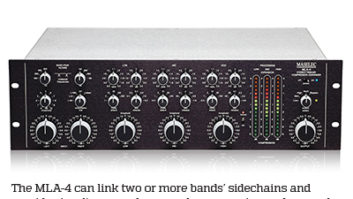

“The basic signal we went through for the vocal chain was a Neumann U47 tube double-compressed through an 1176 and a Distressor EL8 through the 1073 Neve module,” Abraham elaborates. “Drums were cut in Studio B at NRG with a 1073 side console and to 2-inch 16-track on a [Studer] 827 and transferred straight into Pro Tools. For some of the bass, I used API and Neve mic pre’s, a FET 47 and a [Sennheiser] 421 on the cabinet. I had a couple of Shure 57s on the guitar cabinet, through the API 312 mic pre’s and Neve 1073s. I like using the Vocal Stressor by ADR, the Eventide 3500 and TC Electronic Fireworx. Also, the 312 cards are a must-have. The 312s are in a small API sidecar console that goes everywhere with me.”

Assisting Abraham was Anthony “FU” Valcic, with whom he has worked for five-and-a-half years. “As an engineer, I make sure the sounds are right,” Abraham says. “Once I get that comfort zone, I relinquish everything to him while I focus on the musical side. You have to know when not to get too crazy in the engineering side and know when to be a producer.”

This time out, Staind entered the studio with music but no lyrics. Says Mushok, “Changes and progressions are worked out, then Aaron adds the melodies and lyrics to what we’ve done. We’ll play along, and he’ll make up something freeform over it. The lyrics are the last thing written. Usually we just have melody, chorus and verse.”

Adding to the challenge, says Abraham, is the fact that Lewis literally makes it up as he goes along. “He constantly changes melodies, and every take has different lyrics, so when you have him sing something five times, you’ll have it five different ways. So I’d comp what made sense and have him sing that version. He’s probably the easiest guy I ever worked with.”

“Each setting created a new vibe. If we’d get stuck from staying in one place too long, we’d go somewhere else and think things out in a different way.”

— Josh Abraham

Mixes were done by the ubiquitous Andy Wallace, whose credits as a producer, engineer, mixer and musician cover the alphabet, from Alice In Chains to White Zombie. With Staind, as with all of his projects, Wallace’s role is to “spend time learning not only the songs and how they are set up,” he says, “but learning intimately the multitracks and the parts of the performances that are most important and have the most magic. I work with the music to see how I can arrange things to most dramatically present all the songs. It’s a complex situation: You work with it so that it has the most musical consistency and the best effect over the various mediums through which it will be listened to. The actual audio I prepare has to hold up. It’s up to me to accomplish that in as musical a way as possible, which is what all listeners respond to, so it helps to, in addition to making it sound good, make it a good musical event.”

Working with his longtime assistant, Steve Sisco, Wallace mixed at Soundtrack Studios in Manhattan for approximately three weeks. “I use probably less outboard gear than anybody I know,” he says. “We mixed at Studio G using a G Series SSL console, which has Ultimation, an automation package. I mixed down to a Studer half-inch analog 2-track. I ran my mixes simultaneously to that machine, which is the primary machine that mixes are used from in mastering. The other mediums I mixed to are partially for backup and partially for any additional production — a Panasonic DAT and to a Sony DA-78, which is a 24-bit digital recorder. I mix the stereo mix on that with the timecode, which allows me to synchronize the mix to multitrack.

“My outboard gear varies from song to song. I’m very partial to the Lexicon PCM42 delay lines. I usually have a bank of those and a Lexicon 480 processing unit and a Lexicon PCM70. The only real ‘must use’ is my ears, but these things I generally like to have in the control room. There are plenty of other toys there that I may or may not use from time to time — typical things they have, like the Eventide Ultra-Harmonizer, because sometimes someone wants something moved from one verse to another.

“As far as monitors, like the rest of the world, I use Yamaha NS-10 speakers and a pair of Genelec 1031As. Those are the monitors I generally mix on.”

Throughout the process, Wallace was in touch with Abraham and Mushok. “Sometimes there was a technical or artistic direction question,” Wallace says. “But for the most part, it was just to make sure we were on the same page. For the day-to-day activities, Mike was in the studio a fair amount of the time, particularly at the beginning of the project, then he had to return to Massachusetts. If I had a question or wanted him to review a mix, I would send it over the Internet, and, with an ISDN line, he could download it from the server in a matter of minutes, listen to it at home, then call me with various information, suggestions and feedback.”

While both men agree that Break the Cycle is a remarkable album, neither could have predicted the response it received out of the box. “I don’t know that anyone can foresee that,” says Wallace. “I felt the potential was there for a very successful record, but, in hindsight, no, I didn’t see it going through the roof the way it has.”

“Part of what makes a good record is a band with good energy and a positive outlook,” says Abraham. “What transpired here is an amazing record, and it’s a good feeling to know that I worked so hard on something that other people respect. It’s really a big honor to have.”