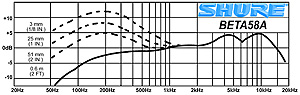

Figure 1: This frequency response chart shows proximity curves and presence boost.

Low-frequency energy management is my personal sonic soapbox. From live sound to broadcast and recording studios, taming bass can free up sonic real estate and simplify solutions that might be “overly complicated” or worse, ineffective.

LET’S START WITH DINNER

The Shure SM58 is perhaps the most copied vocal mic of all, with many variations on the theme. An internal bass roll-off circuit, combined with a robust pop filter, compensates for proximity effect. (See Fig. 1 for frequency response.) Back in 1966, when the SM58 was introduced, psychedelically loud onstage instrument levels made it hard for vocals to cut through—hence, the upper midrange “presence lift” to improve intelligibility.

Despite the built-in highpass filter, the SM58 and its offspring can still let through ample low and low-mid energy. “Mud” radiating from the back of the P.A. stack can cloud the mix, and while it’s cool to hear the human voice resound through the hall like thunder, it is rarely appropriate. Success is often based on the ability to work quickly, so many of our fixes that turn into habits are those that get the job done. Live engineers don’t have the studio engineer’s luxury of time. These days, it’s fairly easy to record a live performance as a multitrack session and play back individual mics for analysis—preferably on the house system, which is time well spent.

TRIMMING THE FACT

A highpass filter is the most obvious fix: Simply raise the roll-off frequency upward until it affects the frequency range that wants to be preserved, and then back it down. Highpass filters typically have continuously variable frequency and fixed-slope options that range from a gentle 6dB/octave (first order) to the more severe 24dB/octave (fourth order). When choosing highpass filter frequencies, it’s helpful to know what musical octaves are being affected—a bass guitar’s open-E string is about 41 Hz, while a guitar’s open-E is about 82 Hz.

Figure 2: Combining highpass and shelving EQ. Notice how a narrow Q setting (2) with a -2.9dB cut makes a sharp transition at 164 Hz, while a wide Q (0.10) with -6dB attenuation affects frequencies beyond 1 kHz.

Shelving EQ may be more appropriate on kick, for example, making room for bass guitar while still preserving the kick’s punch. Figure 2 shows how bandwidth (Q) affects the slope of the shelving curve. See how the 42Hz highpass filter works with a shelving equalizer. Narrow bandwidth (Q of 2) preserves the lowest usable mids around 200 Hz, while the wide bandwidth (Q of 0.10) affects frequencies beyond 1 kHz! (Attenuation is -2.9 dB and -6 dB, respectively.) These settings minimize bass competition in the first two octaves (above open-E) from other sources, such as drums, vocals and instruments.

Studio and broadcast engineers use compression and limiting to narrow dynamic range, raising low-level signals for challenged consumer systems and their even more challenging (and noisy) environments. Despite venue noise (from HVAC and the audience), live engineers do not need to make their sound feel bigger on small speakers, and they have the ultimate cure for background noise. That said, the primary struggle is variable acoustics—venue-to-venue, as well as empty house to full house—and onstage levels, which are slowly being tamed by in-ear monitors and offstage amplifiers.

OUCH!

Designing “presence” into a microphone was an easy fix to compensate for low-frequency mud. But so many mics applying this cure to systems that have ample clarity and power can result in a painful buildup of upper-midrange presence, which happens to be the frequency range where the ear hears very well at all dynamic extremes. Unlike broadcast or studio engineers, live engineers need limiting more than compression to keep the power to inflict pain in check.

Limiters can be full-range or frequency-specific. A de-esser limits high frequencies only (or limits based on sidechain EQ). I am a fan of multiband signal processors because they can do a great job of gluing all of the sounds together. If mixing is a puzzle, a multiband processor can help airbrush the edges of disparate pieces so they seem as one instrument. For me, that happens on the drums and bass submix.

Figure 3: Composite screen from the McDSP ML4000 multiband processor being used to gently limit by about 3 dB (note the red vertical bars). The spectrum has been divided as follows: bass up to 164 Hz, low-mid (164 Hz to 814 Hz), high-mid (814 Hz to 6.18k Hz) and treble (6.18k Hz and above). Threshold, ratio, attack, knee and release can be optimized for each frequency band. EQ can be tweaked via output levels.

A multiband processor’s divide and conquer approach is useful across the board—in broadcast, studio and live applications; on the mix bus and on submixes (like vocals and instruments); and taming the presence region and limiting the potentially painful upper-frequency region (Fig. 3).

THE FINALE

The two primary differences that should make “live” issues easier to detect and resolve are frequency response and dynamic range. While most venues wouldn’t qualify as anyone’s acoustic dream space, the number of low-frequency-capable drivers and the power behind them makes detection easy, as compared to what most broadcast and some mix engineers have to accurately assess as low-frequency energy.

The ability to optimize microphone choice, apply equalization and signal processing are fundamental to all aspects of the audio biz. In live sound, speed and efficiency are key to being, and staying, employed. Experience also plays a huge role, as does disposition and education—whether from a boss, a mentor, a teacher, a book or the manual. No matter how far along in your career, there should always be time for a little sonic woodshedding—sometimes referred to as “doing stuff the hard way.” It’s also one of the best ways to learn.

Eddie recalls the days when multiband processing meant misusing Dolby-A noise reduction. Visit him at www.tangible-technology.com, Facebook and Twitter.