The very name “Santa Monica” conjures up images of the beach, palm trees and an iconic pier, but the Coastal California town is also home to a significant number of sound studios, more than a handful of post-production houses and, of course, the distinguished Remote Control, Hans Zimmer’s home base and composer gestation tank.

Santa Monica is now able to brag about another state-of-the-art facility: composer Benjamin Wallfisch’s The Scoring Lab. The UK-born-and-bred, L.A.-based Wallfisch has a solid amount of composing credits to his name: Shazam!, Mortal Kombat, It and It Chapter 2, The Invisible Man, as well as the upcoming Flash (2023) and the Ron Howard-directed film, Thirteen Lives. So he was well-established in the scoring space when Zimmer brought him to Remote Control, working together on Blade Runner 2049, Dunkirk and Hidden Figures. Building a custom, high-level and progressive studio like The Scoring Lab, however, had been a dream of Wallfisch’s going back to his teenage years.

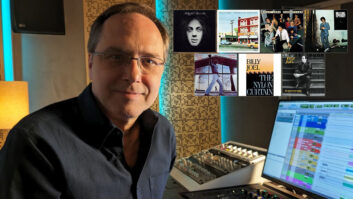

“I grew up with musician parents, and they would often invite me to recording sessions,” says Wallfisch, sitting in The Mix Lab studio of The Scoring Lab’s practical and aesthetically pleasing layout. “They’re classical musicians, so it was always with an orchestra. Sometimes they’d be in churches, sometimes in dedicated studios. I was fascinated with the process. “When I was 15, a production music library gave me a chance to write some news idents,” he continues. “My grandma smuggled me out of high school and dropped me off at CTS Studios in Wembley. This is the ’90s, so they had huge tape machines and a very complex, beautiful desk. For me, it was like walking into Disneyland. That experience cemented my love for the process of creating recorded music.”

Wallfisch is an accomplished pianist with an impressive traditional music education that includes degrees from London’s Guildhall School, the Royal Northern College of Music (“I went in a pianist and came out a composer”), and a master’s from the Royal Academy of Music. Prior to composing film scores, he was conducting world-renowned orchestras. This translated smoothly to scoring, which, in turn, led to the conception of The Scoring Lab.

“The idea to build my own space came out of the practical need for a bigger room,” says Wallfisch. “For seven years, I was in a very small room at Remote Control, trying to do playback meetings with eight, nine clients. It got to the point where you couldn’t fit the people in the room. It’s very rare for bigger rooms to come up at Remote Control, so I started looking for a space.”

IN THE RIGHT SPACE

Wallfisch found a former art gallery in one of Santa Monica’s pristine bow-truss warehouse complexes. He snatched it up and enlisted Peter Grueneisen of nonzero\architecture to design the studio. Grueneisen has his fingerprints all over Remote Control, as well as DreamWorks Animation dub stages and Fox scoring stages, to name just a few spots.

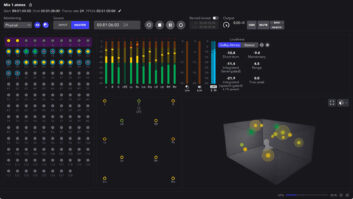

The initial impetus for The Scoring Lab was as a writing space for Wallfisch, but once the composer heard the Dolby Atmos mix of his Blade Runner 2049 score (for which sound mixer Ron Bartlett was nominated for an Academy Award), Wallfisch was determined to build a Dolby Atmos-certified mix room from scratch, while allowing for mixing in 7.1, 5.1 and stereo, as well.

The vision for building his room proved a lot easier than actually getting it completed. The Mix Lab is centered around a 64-channel, dual-operator Avid S6 console with two M40 Master Touch modules, surrounded by an array of speakers: 12 ATC SCM45A Pro monitors for height and surrounds, three ATC SCM150ASL Pro for left, right and center, and three JL Fathom f113v2 subwoofers for the low-frequency effects.

Getting the City of Santa Monica to sign off on this setup, and getting Dolby to sign off on the studio’s Atmos certification, was another story. “The city was saying we couldn’t get a planning permit because we put too much downward force on the framing and it was too dangerous,” says Wallfisch, who spent 18 months building the studio with Grueneisen. “Dolby were incredibly tough and stringent about how the room had to hit their standards, which was great. It meant we were pushed really hard to not cut any corners at all.

“Dolby required ATC SCM45 speakers because of the full-range nature and the size of the room,” he continues. “At that time, ATC didn’t make speakers that can be flown on the ceiling. SCM45s are normally active speakers, so they have very heavy amplifiers. I was adamant about getting ATC speakers, so I talked to them about making us customized speakers, and they did. The ones they created for the studio are passive SCM45s, which takes off most of the weight.”

The Mix Lab, which is floated on 14 inches of sand to reduce transmission, is designed to be adaptable to the user’s needs. As a studio for hire since October 2020, it has seen clients such as the Netflix documentary Operation Varsity Blues: The College Admissions Scandal, scored by Leopold Ross (brother to composer Atticus). Mixed by Christopher Jenkins and Sal Ojeda, it was the first project to be completed at The Mix Lab. The two also mixed Billie Eilish’s music-driven Happier Than Ever Disney+ film in The Mixing Lab.

Some of the other projects mixed there include episodes of Obi-Wan Kenobi and The Orville by Shawn Murphy and Erik Swanson, who also mixed Yo-Yo Ma there. Niko Bolas has mixed Neil Young, Rod Stewart and Lindsey Buckingham in the room, while Alecks Von Korff mixed Muse, Cam Trewin did Rüfüs du Sol and Ari Morris mixed Moneybagg Yo. Mix engineers Steve Genewick, Nick Rivas, Ryan Gilligan, Jon Taylor, Scott Smith and Ken Caillat have also spent time in The Mix Lab.”

FLEXIBILITY BY DESIGN

More than a mix studio, The Mix Lab also serves as a Dolby Atmos mastering space, a dub stage and re-recording studio with an ADR/ overdub booth with top-of-the-line condenser microphones and Grace Design M108 preamps.

Additionally, The Mix Lab has an extensive collection of outboard gear, including a Bricasti Design M7M reverb, Maag Audio EQ4M and Manley Massive Passive equalizers, Shadow Hills compressor and Focusrite 16R, A16R, HD32R and D64R converters. In his technology selections, Wallfisch’s intention was to encourage experimentation by anyone who uses the space.

“Because this technology is still in its infancy, everyone uses it slightly differently,” he says. “What really excited me and motivated me to make this place was the idea that it could become a real hub for people to come through and try things with this collective mentality, where everyone’s still figuring out what it means. We want it to feel like a private living room where you can lock yourself away and do crazy things musically. There are no limits. It’s all about that laboratory kind of philosophy.”

Universal Music Publishing Group furnished Wallfisch with the masters of songs from some of their top artists to serve as in-house demos. These included The Weeknd’s “Blinding Lights” and Billie Eilish’s “Bad Guy.” These sound huge and crystal clear when Wallfisch plays them back through the ATCs. His reference for an immersive “upmix” is Elton John’s “Rocket Man” by Greg Penny, which he likes, in part, for its simplicity.

“It is a powerful, emotional experience when you hear non-film music mixed in Atmos,” Wallfisch says. “The clarity of the vocal performance because it’s completely isolated on one speaker, the exact nuances of how the percussionist might be performing—these make you feel like you are in the room with them. Hearing upmixes of The Beatles, you realize just how pioneering the mixing was, how bold it was. They were using the limitations of putting everything left and center as a feature. Now, when you’re able to do the exact opposite, it’s almost like you’re checking yourself not to go overboard, and to still start from that place where the music is what is making the decisions, not the technology.”

MIXING UP THE PROCESS

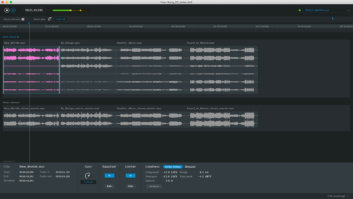

When writing and recording, Wallfisch keeps his focus on the music and the performance, and not on how it might be mixed immersively. His conducting experience comes into play when arranging the musicians, never approaching the orchestra as a fixed entity with the traditional placement of the instruments.

Says Wallfisch, “Depending on the project, sometimes I have the violins opposite each other and the bass in the middle, because it’s a score where there’s a lot of melody in the strings and I don’t want it all to be coming from the left. Sometimes I’ll record the brass separately and have the horns in the middle. I may pan a little bit to the left in the final just so the moments when the horns are absolutely in the forefront of the melody; you want them on the screen.

“Even though the combination of orchestral instruments has been around for years,” he continues, “we’ve only gotten started with what we can do with an orchestra. There’s still so much uncharted territory, and that includes how it’s recorded, for sure—but you don’t want to get too tricks-y. You don’t want to distract. It’s about using Atmos in a way where you’re giving that performance of the orchestra its best possible airing.”

To that end, Wallfisch works collaboratively with engineers in the studio to determine the best microphone placement. For Thirteen Lives, which he recorded at Air Studios with Peter Cobbin, they had an additional pair of microphones exactly matched with the wide microphones hung seven feet above. These would go to the speakers on the outer part of the Atmos bed. Another four microphones were placed in a square around where the surround microphone would be. An additional four microphones were hung directly above the orchestra, which would pick up certain parts more so than others.

“Making an Atmos mix is not necessarily about absolute realism,” Wallfisch says. “It’s about a perceived immersion. That can be something you create after the fact with processing and panning and reverbs. In that mix, we used the quad of surround microphones with a lot of creative panning with reverbs and using slight delays on the other microphones, sending them into the Atmos configuration like that.”

In contrast, for Blade Runner 2049, which was scored entirely with electronics, the masters were in 5.1 and the re-recording mixer, Ron Bartlett, created the entire Atmos experience and it worked perfectly. Wallfisch feels it’s best to have a detailed version and one that is less “channel-intensive” or “object-intensive.”

“I’ve always tried to not get in the way of the re-recording mixer when it comes to Atmos decision-making,” Wallfisch says. “What I’m finding now, especially with the spatial audio requirements of music releases, I’ll do an Atmos mix and a 7.1 mix at the same time so there are options. Then we do an album mix in full Atmos, where we have time to really dial it in for the listening experience. That’s probably going to become more and more how we work. Maybe eventually we’ll get away from the 7.1 part of that process. It’s a transition right now.”

Wallfisch points out that composers have the luxury of having their music presented to audiences in a movie theater in Atmos, which pushes him to embrace the musical storytelling part of the experience, as well as the physical three-dimensional experience of the music.

“The flip side of that is, it can be very tempting to go overboard,” he acknowledges. “You’ve got joysticks on the mixing board. You’ve got an arpeggiated synth. The temptation is to fly that all around the theater—but is that going to serve that moment dramatically? Is it going to just be distracting? It’s all about the context. It’s easy to underestimate the raw power of an orchestra, especially in film music. Capturing the power of that live experience in as much detail as possible, is what I’m trying to do when it comes to Atmos.”