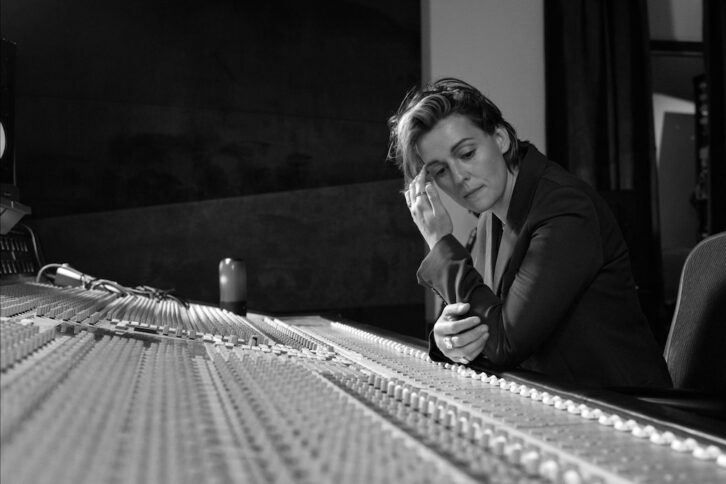

Brandi Carlile knows that realizing music’s full power begins with seeing the whole artist, the whole person, from every angle. As she says, “I’m only interested in 360 degrees.” For Carlile, it’s not so much about the how, but the why. Drawing on her own journey as a musician—and from insights gained through collaborations with the likes of producers Rick Rubin, Trina Shoemaker and Dave Cobb—she takes an all-in approach that’s at the same time all about the artist.

Carlile burst onto the scene in 2005 with her self-titled debut, building a loyal following from the jump. Her 2007 follow-up, The Story, earned critical acclaim, and in the ensuing years, she released four more albums, while writing and touring tirelessly—but it was 2018’s By the Way, I Forgive You that made her a household name, earning her six Grammy nominations and three wins.

In 2019, Carlile formed supergroup The Highwomen with Amanda Shires, Maren Morris and Natalie Hemby. Rockstar status cemented, she went on to release In These Silent Days in 2021, which reaped armloads of awards and inspired a companion acoustic album, In the Canyon Haze, and an IMAX concert film that she produced.

Carlile’s journey to the producer’s seat was fueled by what she affectionately terms “fanput”: a deep adoration for fellow artists; a desire to immerse herself in their creative process; and a commitment to amplifying deserving voices across generations.

She’s recently helmed albums by Lucius and The Secret Sisters. Tanya Tucker’s 2019 album, While I’m Livin’, which Carlile coproduced with Shooter Jennings, ushered in a renaissance era for the country legend, earning Tucker new generations of fans and her first Grammy Awards in her five-decade career. This year, Carlile produced records with Brandy Clark and emerging artist Tish Melton, and reunited with Jennings to produce Tucker’s follow-up, Sweet Western Sound. Carlile’s collaborations with Joni Mitchell led to Mitchell’s return to the Newport Folk Festival stage and a resulting live album, which she produced.

Mix sat down with Carlile to learn how her admiration and empathy for her musical heroes unlocks creative flow, how she channels edge-of-your-seat rock-and-roll energy in the studio, and how she walks that delicate line between serving the artist and serving the song.

What drew you to producing?

I think my propensity for “fanput”—you know, becoming a really big fan of an artist and wanting to get involved with the output, and being able to work with an artist at a level that was really interesting to me.

You were self-producing for a time. Why did you move away from that?

I learned a lesson from Dave Cobb: I might be able to bring an artist into themselves if I feel passionately about it, but nobody really has brought me into myself as an artist as Dave Cobb did on my last two albums. He took me to a place where I know that I need to work in communion and collaboration with a producer and a visionary when I work on my own music, because I’m just too close to it.

When I quote-unquote “self-produced” Bear Creek and The Firewatcher’s Daughter, I really feel like that was more of a situation where I was riding shotgun with Trina Shoemaker. I think Trina’s innate feminine wisdom led her to the understanding that I needed to have a certain amount of autonomy and authority in the studio over myself because I had come out of the studio with such important characters on my prior records.

She was really happy to set some things about herself aside, and when I look back on it now, I have a lot of admiration for her because of that. When I really think about those times and knowing what it actually takes to make an album now as a producer, I think that those things were as much produced by Trina Shoemaker as me, possibly more.

You’ve worked with great producers: Trina, Rick Rubin, Dave Cobb, Shooter Jennings. What are some of their perspectives that you’ve taken forward with artists that you work with?

There are so many ways, and they’re all such different characters. My first experiences with Rick Rubin were just mystical, you know? The things that he was saying and leading me to try and find out about myself were blowing my mind. I didn’t understand the music business. I had only been on an airplane a couple of times by the time I met him. It was just a profound experience with someone who had such an air of mysticism about him, and the things he was saying were really absorbing to me.

I met T Bone Burnett shortly after that and went in the studio with him; he was just so involved, he was just in the band and in my psyche and I was just learning.

T Bone Burnett told you that rock and roll isn’t a genre, it’s a risk that you take. You’ve done a lot of live tracking with artists in the studio. Did he influence you in that sense?

I think that the way I make albums now, with myself and other artists, wouldn’t be what it is without T Bone Burnett, and the way we set up in a room and learned how to record an album live with a certain amount of analog-mindedness.

We have tools now, and we use those tools, but if we think like we don’t have them, we can create some really edge-of-your-seat music.

How did you connect with Shooter Jennings?

We met at Johnny Cash’s 80th birthday party at the Moody Theater in Austin, Texas. We were all tributing Cash because he was already gone at that point. Cash was a theme in the early part of my career in so many ways, because when I met Rick Rubin, he was still working on American Recordings, one of the later volumes, and so Cash was always sort of in the ether for me.

When I met Shooter, we just stuck together like glue all night long and became really good friends. I didn’t even know Shooter was a producer at that time, but I knew I just wanted him to be a part of whatever I did next. When it was time to make By The Way, I Forgive You, it was a phone call that he wasn’t expecting—but I told him I’d call.