Sometime late into the night in May 1969, Robert Lamm returned home from one of his band’s regular gigs at Whisky a Go-Go on the Sunset Strip and picked up a 12-string electric guitar that was missing some strings. Before he finally went to sleep, he had written a song for his band’s next album, not knowing it would become a guitar theme for every guitarist who would come thereafter. The band was Chicago, the song “25 or 6 to 4.”

The group had formed in Chicago two years earlier as The Big Thing, though record producer James Guercio (The Buckinghams, Blood, Sweat & Tears), who had become their manager and, later, producer, suggested a more comely name, Chicago Transit Authority. “The sooner we could change that name, the better,” laughs original drummer Danny Seraphine.

Seeking to get the band signed to a label, Guercio brought CTA to Los Angeles in June 1968. “We were making some serious coin as a club act, playing some pretty nice clubs in Chicago, Milwaukee and Indianapolis,” recalls trombonist James Pankow. “But we reached a point where we asked ourselves, ‘Do we want to be the biggest nightclub act in the Midwest, or do we want to be a national act and make records?’ And if we do, we gotta get the hell out of Chicago.”

Pankow, Seraphine, bassist/singer Peter Cetera and saxophonist Walt Parazaider threw their personal items and the band’s belongings into U-Haul trailers and drove west. Lamm, guitarist Terry Kath and trumpet player Lee Loughnane preferred to fly.

To house the band, Guercio rented a home at 2120 Holly Drive, a three-bedroom bungalow built in 1920 in the Hollywood Hills, just north of Cahuenga and the Hollywood Freeway. Pankow, Lamm, Kath, Loughlane and two roadies staked out territory within the small house, while Cetera, Parazaider and Seraphine—the married guys—were set up in a pair of apartment buildings just around the corner, on Primrose Avenue.

“We were beginning a musician’s life,” says Lamm. “Everything was writing a song or practicing your axe, going out and playing gigs. Everything was about music. It was a very uplifting time, and, to us, it seemed normal.” They soon became the “house band” at The Whisky, and Guercio would invite record industry executives to hear them, eventually landing a contract with Columbia Records.

At the beginning of the following year, in late January/early February, Guercio brought the band to CBS Studios at 49 East 52nd Street in New York to record their first album, Chicago Transit Authority. In Guercio, the band found its perfect champion. “He was working with guys who had never been in a studio,” Lamm explains. “We were sort of amateurs; we weren’t session guys. But he still had faith in himself and faith in the possibility that we could actually gel in the studio and perform as a group. Because we were still learning how to be a group. I don’t know how many producers would have had the patience. And many of them don’t.”

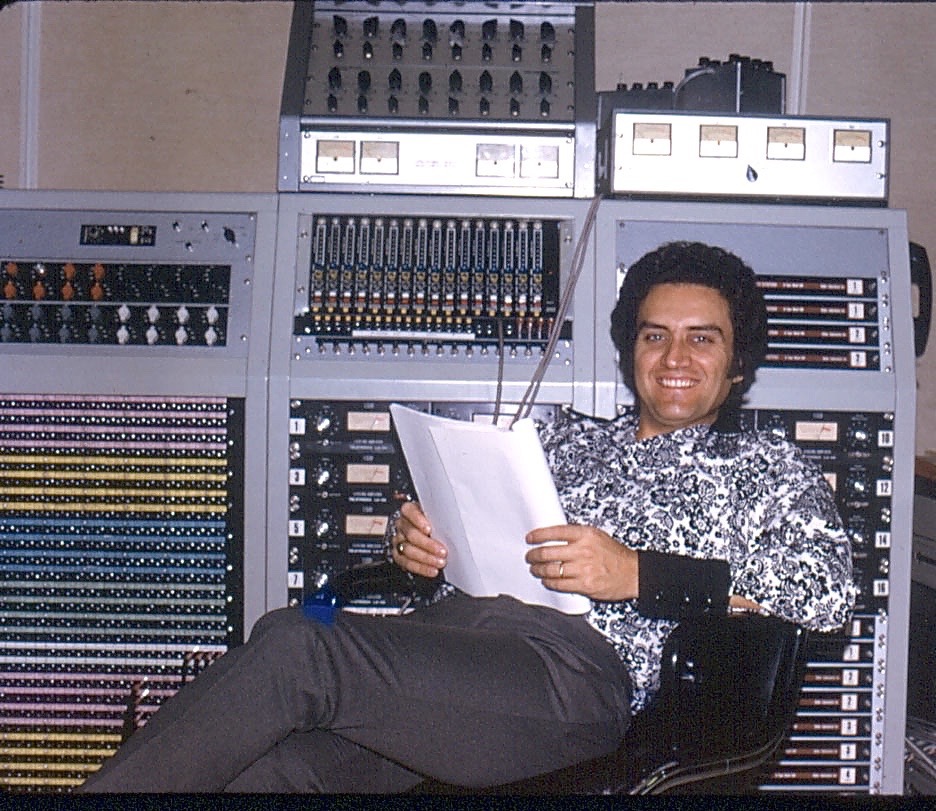

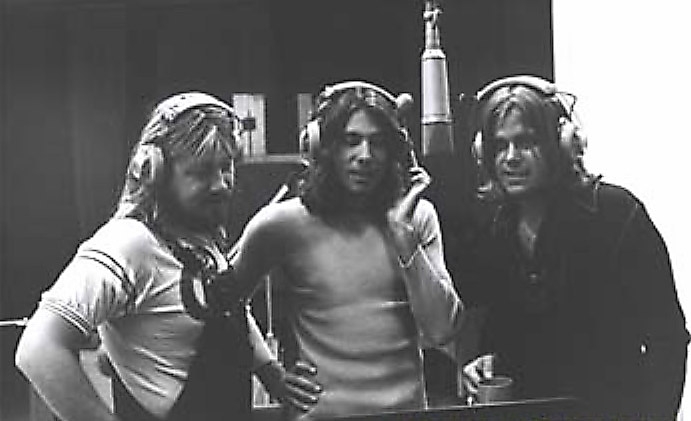

Roy Halee began engineering the album, but Guercio soon shifted to Fred Catero (“a jazz engineer,” he notes). Work took place on 8-track in the smaller Studio E, located on the building’s fourth floor, while Halee worked with Simon & Garfunkel in the more spacious Studio B on the second floor. “Fred was a very talented, quick engineer. I learned a lot from him,” states colleague and protégé Don Puluse. Guercio echoed the praise: “I did that album in 14 days—10 days recording and overdubbing and three or four days mixing.”

The album was released on April 28—one of their regular Whisky dates—containing a number of what would become signature hits for the band: Lamm’s “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?,” “Beginnings” and The Spencer Davis Group’s “I’m a Man.” The group received a Grammy nomination for Best New Artist the following year.

On to Chicago

It wasn’t long, though, before Guercio had them back in the studio recording their next 2-LP set (this time, under their permanent name “Chicago,” truncated to avoid legal action from the transit authority of the same name). With the success of CTA, the band was now on the road, playing bigger and bigger venues, so recording became a “catch ‘em when you can” venture. “I had to deal with them when I could. And I had to break it into short periods,” the producer says. Notes Seraphine, “Whenever we had a set of songs to record, we would go to the studio.”

The first batch to be recorded was Pankow’s “Ballet For a Girl in Buchannon,” a 13-minute suite consisting of seven songs—two of which would become mammoth hits on their own, “Make Me Smile” and “Colour My World.” Recording for the “Ballet” was tracked by Don Puluse, who had recorded The Buckinghams’ “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” for Guercio two years earlier, the first time the pair worked together, and about a year after Puluse joined CBS.

Classically trained, and a former clarinetist with the United States Marine Band in Washington, Puluse eventually left the military and completed degrees at the Eastman School of Music, including a master’s degree and engineering degree. He was hired as a Production Trainee at CBS and began working on classical music recordings, first as an editor.

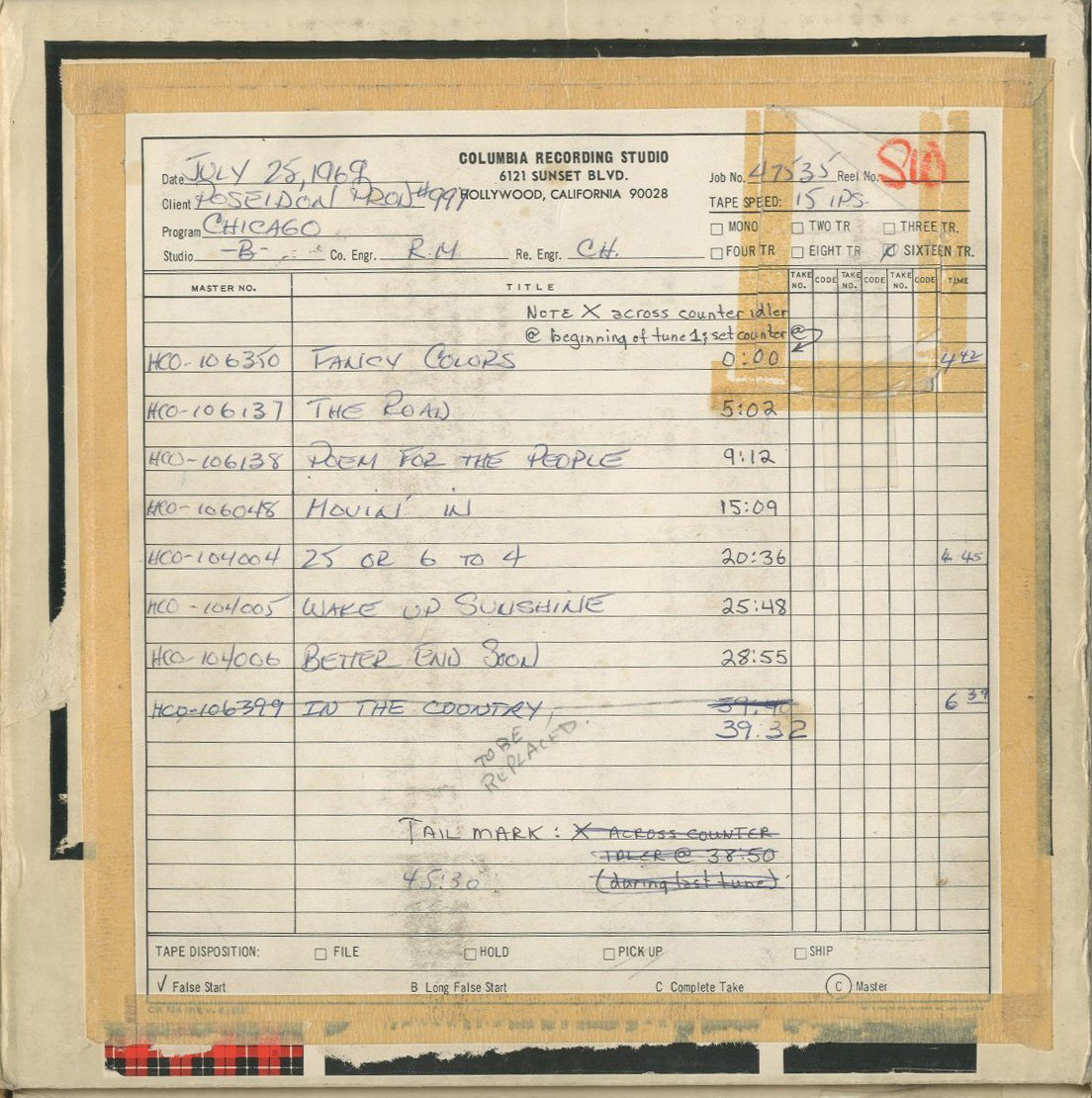

Touring, meanwhile, continued mostly around the Northeast in late June and the first half of July, until another batch of songs was ready to record. Two weeks of sessions were set up in Studio B at CBS Studios in Hollywood, at CBS Columbia Square, located at 6121 Sunset Blvd.

Engineering was handled by a British engineer by the name of Brian Ross-Myring, assisted by tape operator (or “Co-Engineer,” as identified on the tape box) Chris Hinshaw. Though Guercio had never produced a recording with Ross-Myring tracking, he did know him from a session three years earlier, Chad & Jeremy’s “Distant Shores,” which Guercio not only wrote, but played on as a studio musician.

Thursday July 24 saw the recording of two new Lamm compositions, “Wake Up Sunshine” and another with an unusual title, “25 or 6 to 4,” both recorded in the evening with just the rhythm section present.

By this time, a year after arriving in L.A., much of the band had all but abandoned the Holly Drive house (though not completely). “I lived with a group of kids who had moved to L.A. from Chicago, a couple blocks up the street from The Whisky,” Lamm recalls. “It was a great old, large California bungalow. One of the girls who lived there had had a boyfriend who was in a band, and who was out of the scene, but he left his stuff behind.”

The musician had had an endorsement deal with Baldwin, and indeed left behind a Baldwin electric 12-string guitar—missing its two low E-strings—and an electric harpsichord, which Lamm augmented with a rented piano. “That was my writing studio.”

One night, after returning from a gig at The Whisky (likely during their five-day stand from May 15-19), Lamm did what he usually did—“You know, come home late at night and sit at the piano for a while and see what was what before I went to sleep.” Sitting “cross-legged on the floor,” he grabbed the 10-string guitar. “I had the guitar riff, which I played, and I had this melody, which I sang along with the riff. Then, once I sat at the piano and fleshed out the changes, and then the release, it sort of all came together. I was really just developing this musical idea between the riff that the guitar would play and the melody on top of it. And a place for the horns to show off their stuff.”

The problem was, what was the song about? “Because I was writing it very late at night, and I’m looking out over the Hollywood Hills, looking down into L.A., I could see the lights on the tops of the tall buildings, flashing and glowing,” (“Flashing lights against the sky”). “So I just thought that, for now, I’ll just describe what I’m thinking and what I’m seeing and what I’m doing. And what I was trying to do was write a song. So the song really describes the process of writing that song. Which was kind of uninteresting and boring.”

It was indeed quite late, so he looked at the antique clock hanging across the room to see the time. “I couldn’t quite tell where the hands of the clock were pointing. It was 25 or 26 minutes before 4 a.m. I didn’t expect to keep those words, I expected to replace them with some actual lyrics. But it ended up working out okay.”

The next day, since Chicago was set up down at The Whisky, Lamm brought in the song to introduce it to the band. “When Robert brought it to us, we immediately connected with it,” Pankow recalls. “It was rock and roll, yet it had a really cool approach to it with the horns. It was another Robert Lamm song where I loved what he did.”

The recordings took place in CBS’s Studio B, built from what remained of one of CBS’s famous West Coast radio theater studios. “It was a big room, with a high ceiling—a good room for live,” Seraphine remembers. “I had baffles all around me. And we were arranged in a semi-circle, with Peter always close to me, and Terry on the other side. We always liked to see each other.”

Basic tracking included Lamm on the studio’s Steinway piano, Kath on one of four electric guitar parts he would play, Cetera on bass, and Seraphine on, unusually, two drum parts.

One thing that is evident from listening to Chicago is, despite his later reputation mainly for ballad singing, Cetera was a remarkable bass player, something heard across this album and any of the era. “He was really challenged by a lot of the songs, compared to the kinds of things he had played up to that point, before Chicago,” Lamm remarks. “But once we were throwing a lot of harmonic and time change stuff at him, he stayed with it. I always thought that his performance on the first album was amazing.”

Cetera was, in fact, playing “under duress,” Lamm laughs. “Peter always played with his finger, but Jimmy [Guercio] made him play with a pick, to get that attack. So Peter was not very happy with that part of it.” Says Guercio, “I told him, ‘You’re a great player onstage, in a club, Peter, but I need definition.’ And he said, ‘I don’t play with a pick,’ so I said, ‘Well, if you don’t play with a pick, I’m gonna play with a pick. So make your choice now,’ and I walked back into the control room.’”

And though he typically played his own Fender bass, on these recordings he played Guercio’s Fender Precision, which the producer had picked up for $200 in 1963-4, which still had its original Fender strings. The amp was either a Fender Bassman or Showman, which, Guercio notes, “You had to put the head down on the floor, because the tubes would rattle.” And, like all of the instruments, it was miked with one of Guercio’s mics of choice, either Neumann U67s or U87s. [The raw recording reveals, by the way, that, for “25 or 6 to 4,” Cetera played not with a pick, by this time, but with the back of his fingernail, according to Tim Jessup, the band’s current engineer, who studied the multitrack recording for us.]

The signature sound of “25 or 6 to 4,” of course, is the guitar riff, played on the recording by Terry Kath. The guitarist played through a Fender Concert amp, modified, Guercio says, like all things Kath. “Terry was always playing with shit,” the producer laughs. “He had this weird 1950s hi-fi preamp or something, like from a McIntosh, he would go through first. I don’t know what it was, but however he got that sound, it was a miracle. That’s what I wanted.”

“I had very little to do with the sounds Terry got, which were really outstanding, signal processing-wise,” notes Puluse, who mixed the album. “Most of that was done with his electronics.”

Kath played the riff over three parts, one during tracking and two in overdubs. The live track, on Track 3 of the 16-track tape, was a clean one, with no distortion, the guitarist playing the riff in octaves, plus some guitar “chinks.” A second pass on Track 4 (which Guercio labeled “GIT FUNK / FUNK RHY” (rhythm) on his handwritten track sheets), played in parallel, this time using an overdriven amp distortion, much like a fuzz bass. A third, on Track 6, labeled “NEW FUZZ,” featured what Jessup says appears to be distortion from a pedal/outboard device. “I wanted three guitars, with different sounds, to get the stereo guitar effect I wanted,” Guercio explains. “I worked with Terry on that; he was the key to this record.”

His astounding guitar solo track, made of three different solo parts, was recorded on Track 8 as an overdub, which Guercio says was built out of several passes and a small number of punch-ins (though the tape reveals only the single track, perhaps indicative of other tracks reused/wiped during other overdubs). The same track also contains Kath’s many accent parts, heard throughout the song. It remains one of rock’s great solo guitar tracks.

After hearing the song for the first time, Seraphine made a decision. “I said I wanted to do two drumkits. I told Jimmy, ‘I want to do two drum passes, one with just straight time,’” with a second recorded as an overdub with more accents and detail, including his five-stroke roll. “In those days, I was doing a lot of melodic fills. I was very much influenced by Hal Blaine’s playing in his studio work.”

Seraphine’s kit, at this point, was a white marine pearl Rogers set, with a 24-inch kick drum, a wood Dynasonic snare, with a 13-inch double-headed tom. In addition, he had 12- and 14-inch concert toms and a 16-inch traditional floor tom. “My biggest nightmare with him was the bass drum,” Guercio chuckles. “I’d want to deaden it. I put a pillow in front of the head on the inside. Drummers don’t like that.”

The first pass was recorded during basic tracking, onto Track 7, in mono, requiring Guercio to have Ross-Myring reset his mic levels. “We were sitting there, I’m listening to every mic, and setting the mics, and finally just said, ‘We’re mono-ing this,’” the producer recalls. The second pass, recorded next (and in absence of the rest of the band), was placed on Track 5.

“The band came into the control room, and they were pissed!” Seraphine laughs. “’What’s he doing, two drums? What a waste of time!’ Jimmy just shrugged his shoulders, and he shut it down. ‘Cause Jimmy loved drums. He loved the idea, but I never got to fully develop it. You can hear, there’s a little bit of shakiness, a little bit of rub there, which kind of adds to it. Plus, the two kick drums are playing at the same time, which was really cool.”

Cetera had one very big challenge facing him when recording vocals for this album. On May 20, a few days after Lamm wrote the song and introduced it to the band, Cetera, Kath, Lamm, Parazaider and Seraphine attended a baseball game at Dodger Stadium, to see their beloved Chicago Cubs beat the Dodgers 7-0. Four marines apparently didn’t take kindly to a jubilant “long-haired rock ‘n roller,” the singer recalled in the Chicago box set liner notes, and a fight ensued, resulting in Cetera’s jaw being broken in three places—and wired shut for several months.

That apparently was still the case when this recording was made, as both Guercio and Loughnane recall. “He had to learn to sing differently,” the producer explains. “I told him, ‘I can’t wait, we’re gonna do this.’” The bassist learned to sing with his teeth clenched closed (due to the wires), a style that has remained with him, to a large degree, becoming somewhat of a trademark. Regardless, he turned in a remarkable performance.

The following evening, the full band returned to record “It Better End Soon,” and, after the six-hour session ended at 1 a.m., Ross-Myring prepared a comp reel of the two weeks’ work—seven songs, coming in at 28:55, enough for a whole album in itself, if it had been desired.

The Horns of Chicago

The horn sound for Chicago was unique, both at the time and still today. Most horn sections on rock, R&B and soul records of the day offered a pad or chord, with the various musicians playing in unison. Pankow, however, created a signature sound and use of horns.

“I knew it had to be as unique as the direction of the music, to start using the brass as a lead line, instead of an afterthought,” he says. “So I conceptualized the horn section as a main character in the story, while being careful not to step on the toes of the other main characters. If you take the horns out and throw some extra words on the track, it could be a second vocal.”

And, given that the arranger was a trombonist, Pankow typically approached the brass with a trombone lead. “That’s another aspect of the uniqueness of our section, it’s got a trombone-oriented section,” he adds. “My ear is trombone-centric; that’s what I hear. So I put the sense of the lead voice in the trombone. It makes us unique and it makes the section thick and fat, versus so many sections that maybe have a token trombone.”

For “25 or 6 to 4,” Lamm, knowing the trombone-centric style of the band’s horns, even wrote what became signature bits that Pankow would play. “He’s playing a line that ascends, and the other two are playing a more static line.” Notes Pankow of his own arrangement elements of the track, “It’s a song about writing a song. I sang along with the vocals and hummed a solo in my head, and that became a melodic horn line, and I voiced it where appropriate.”

The other element that made Chicago’s horns sound so unique was the way Guercio recorded them, beginning with this album, Chicago. While CTA was recorded at CBS New York on 8-track, allowing for a single horn track, by 1969, via the 16-track tape machines present in Hollywood, he decided to take a new approach.

The basic arrangement was recorded onto one track. miking, again, with his favorite U67s and U87s. A second pass, B, was then recorded, but mixed together live with A onto another track. Yet a third pass, C, was recorded, again mixed together live with A, onto a third track. And, once done, pass A was wiped, to make the track available for more overdubs. “Once we were done, I was stuck with it. It was staying,” states Guercio.

Now, of course, if the two tracks, with A+B and A+C, were panned left and right, the listener would mostly hear A in the center. “That was something we wanted to avoid,” explains Puluse. To prevent that from happening, “We would EQ one a little bit, and keep the level of ‘A’ so that it wouldn’t be too loud.” Adds Guercio, “They’re not simply doubling. Generation ‘A’ is the same foundation, but it’s not at the same level and is mixed differently. So now we ended up with what sounded like four sets of horns, not two.”

On top of that, Pankow would change up the arrangements for the B and C passes. “I would voice switch,” having himself, Loughlane and Parazaider switch parts. “I would say, ‘Okay, Lee, you play the trombone part, which is up an octave in the bass clef, on your trumpet. And Walt, you play the trumpet part above the staff, because the tenor sounds an octave lower. And I’ll play the sax part, above the staff, in the bass clef.’ Or sometimes we would experiment and not only voice switch, but I would have guys play alternate notes in the chords, so we would flesh out 6/9 or a 7/11 in the chord or a raised 9th. You have to not only voice switch to fatten the chord, but you have to add alternate voicings on overdubs. And that’s how it sounds like 40 horns, instead of three. It created this wall of sound.”

“Pankow is so talented at arranging,” Lamm says of his bandmate. “He was very good at the unique voicings, to make the most of three horns. And that, combined with how Jimmy Guercio recorded them, it created our signature horn sound. He really made them sound distinctive and unique, and nothing like it had been done before.”

The same method was used by Guercio when tracking background vocals, which he did upon the band’s return to L.A. on August 19-20. On “25 or 6 to 4,” the trio recorded an A pass, then tracked a B mixed live with A, and the same for the C pass, again EQd differently to give each pass its own tone and voice. But, in this case, the original A pass was kept and included in the mix, as well, placed in the center, providing a total of 15 voices. “With the way it’s tracked,” says Tim Jessup, “you’ve got six voices on one side, three in the center and another six on the other side.”

Mixing

The album was still far from complete. Once Kath’s vocal was added, the tapes were brought to Puluse at the CBS 42nd Street studio in New York. Mixing typically took place in one of the 10 editing rooms on the fourth floor, as was the case with Chicago. By this time, Puluse could mix his own recordings, though that was not the case when he started at the studio. “A few years earlier, the engineer in the studio would do the recording, and then it went up to the 4th floor to a mixing engineer,” he explains. “But when rock and roll came in, the groups and producers were not going to work in the studio with one person, with complicated tracks, and then have it go up to a room and be mixed with somebody else. It changed the whole culture there, really.”

Each mix room had 16-track Ampex and 3M tape machines, mixing to Ampex 350 2-track ¼-inch. “Every channel in those rooms had EQP Pultec limiters and a Kepex noise gate. And there were selectable Universal Audio 1176s and LA2As and 3As,” Puluse recalls. “So we had choices. There was nothing in the signal path that couldn’t be changed.”

For reverb, you turned to one place. “There was one room, on the 3rd floor, and it was like a morgue of EMT plate reverbs, 40 or so of them in this one room,” Puluse says. “You’d go downstairs and select which one you wanted to use via the patchbay— if it wasn’t being used by somebody else—and you could adjust that EMT.” Spring reverbs and other options were also available, but Puluse tended to stick with the plates.

“I would always experiment with the ‘chambers,’” as he typically refers to the plates. “You could pre-delay them and you could post-delay them. You could change the time, and you could noise gate the end, if you wanted to. But I very seldom used noise gates for anything but a correction. I didn’t use it for effects on Chicago.”

Mixing was performed on one of CBS’s custom consoles, built by chief engineer Eric Porterfield for each mix room. “They had Penny and Giles faders, as well as rotary pots, and there were two sets, one above the other,” Puluse says. “We had a lot of speakers, and a lot of problems with speakers at that time. For consistency, we had chosen Voice of The Theater A7s, which was a very unusual choice. The ‘new’ version, with the decorator box, not the exposed box. Before that we had 604s, the ‘Big Reds.’ And we always had little Auratones, so that we could just check the mix, to see how it would sound on a smaller system.”

Puluse would always be sure to create a rough mix following a recording session, to have available during mixing. “When you do a rough mix, it’s very organic. And then you go into a room—even in the same studio—and you start spending time perfecting things, and you really lose that original feel. So it’s always important to keep the rough as a reference.

“Jimmy [Guercio] really wanted a very tight, present sound,” he continues. “Those recordings were really pretty dry. We tried to get the tightness, to make [the horns] very present. That’s why everything was pretty close-miked. I wasn’t going for a big room sound on these things.”

Kath’s guitars were given analog delays, again, via the EMT plates. “Sometimes, I would actually take the echo and reverb the echo. But very subtly. We weren’t adding a lot of effects to this music. We were making it sound like the room.”

For vocals, Puluse would limit his use of compression. “I try to learn the music and hand-gain things. Background vocals, I probably used an 1176. But for lead vocals, I would only a little. I would try not to use it as a crutch.”

Following mixing, the album was mastered by one of several mastering engineers up on the 5th floor (Puluse points to two of note, Jack Ashkenazi and Vlado Meller). The album was released shortly thereafter, on January 26, 1970, with “25 or 6 to 4” issued as a single in June (backed with “Where Do We Go From Here”), appearing as a carefully cut single edit, paring the song down from 4:50 to 2:52 (which Puluse recalls doing himself) by eliminating the second verse and chorus and two-thirds of Kath’s solo. It reached No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.

“Robert created a rock and roll anthem with that song,” says James Pankow. “Every beginning guitar player plays that riff. And who would have thought it would have started with a guy sitting on the floor with a half-strung 12-string guitar, looking out the window and writing down how he felt at 4 in the morning cause he’s shot from playing a gig. It’s a masterpiece. These songs are timeless.”