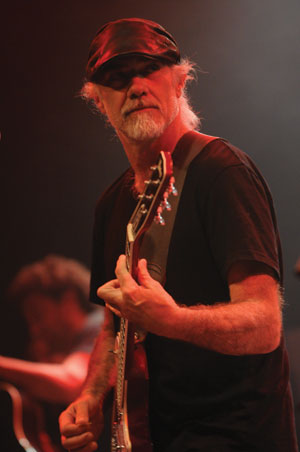

Photo: Bill Ellison

There are people who know Chris Pelonis the Musician, and he is a monster guitar player. Others know him as Chris the Engineer/Producer or Chris the Singer-Songwriter. Closer to home, he might be known as Chris the Martial Arts Guy, Chris the Surfer, Chris of Chris & Pits BBQ or Chris the Choir Director. Lately it’s been Chris the Photographer. In our industry, he is known as Chris the Studio Designer or Chris the Speaker Maker.

Chris Pelonis is all of those things. He’s also restless, passionate, focused, determined and sometimes ornery—“like a dog on a sock,” says his friend Jeff Bridges—if a particular project or action moves him, working 15 and 20 hour days for weeks at a time, sometimes driving those around him crazy. At the same time he is kind, loyal and sincere, a compassionate man raised by compassionate parents. He gives as freely of his time helping raise money for mudslide victims in La Conchita, near his home, as he does putting in the extra hours designing world-class studios for Sony PlayStation. At the age of 55, he has already put in his 10,000 hours in Music, Recording, Photography, Speaker Manufacturing, Studio Design, Martial Arts, Surfing, Volunteerism, Family and probably a few more areas. Most people try for one.

The professional audio industry seems to attract more than its share of the most interesting and talented people, the type with that rare ability to merge technological aptitude and creative expression. Engineers and producers are passionate people, practically by definition, and most will bring those traits to their lives outside of audio. It’s in the blood. Despite his vast accomplishments, Chris Pelonis is not a household name in our industry, the way many others are, but in my 25 years at Mix, I have come across just a handful of people as complete in their talents and approach to audio, creatively and technically. He is more in demand today than he ever has been, from clients new and old. That is why he is on this month’s cover of Mix. It helps that he’s a good man.

“I’ve found that when I start preparing for a role [in a film], I’ll get song ideas, I’ll start working with ceramics,” Bridges says. “My mind will go in other creative ways. That used to distract me, and I used to get mad at myself. But I’ve found that everything informs each other. That’s what it is about Chris: All of his time spent on designing speakers and studios and sound informs his music in such a beautiful way. His martial arts training informs his creativity, it informs his speakers—that discipline and learning. Then he has a deep spiritual side that informs his work, just how he deals with people. He’s got a lot of soul.”

MUSIC

Pelonis, center left, with Jeff Bridges and the Abiders, on tour in 2014.

Photo: Bill Ellison

Most Mix readers won’t be aware of just how good a guitarist or recording artist Pelonis is. It’s not something he talks about a lot, but Bridges, David Crosby, Michael McDonald, Jackson Browne, Jimmy Messina—his friends in and around Santa Barbara—all speak of his playing first, then his speakers, then his design. Music is the bedrock of nearly everything he does, as he considers himself a “tone freak,” whether onstage or building a studio space.

Pelonis grew up in a musical family, with an aunt who was a prodigy on piano, a grandfather who played flute and a mother who loved Sinatra. His grandparents owned a restaurant in Hollywood, along with the building next door that housed David Hassinger’s Sound Factory in the 1960s and ’70s. He was surrounded by music, and support. One of his earliest memories goes back to age 4, when his sister brought home a nylon string guitar. He stole it from her room and never gave it back.

“I remember thinking, ‘What’s this? I have to do this,’” Pelonis recalls. “I just heard what happened when I hit the strings, and that was it. Early on my mom encouraged it, and I took folk guitar lessons—‘If I Had a Hammer,’ that sort of thing. They had all these funny names for different strumming techniques, like the Pizza. I remember the Pizza to this day. I learned chords.

“Then, like with most things in my life, I got pretty obsessive,” he continues. “Later I got song books and listened to records and did that. Then even later on, in my late teens, I went to Dick Grove’s music school and did a semester in their guitar program. I was already doing sessions at that point, but I wanted to get better. A guy there told me (I already knew more than I was going to learn there) that the pace there was going to hold me back, and to leave and go buy these theory books. So I did.”

Though largely self-taught in nearly everything he’s done, Pelonis will continually reference the musicians, producers and engineers he learned from. For music theory, there was Larry Sampson in Orange County.

“I went through his whole curriculum,” Pelonis says. “He was teaching me these Japanese pentatonic scales when we were talking about building chord progressions. In theory, with any scale you should be able to take various notes from the scale, play them together, and they’ll create a chord. There are major scales, minor scales, Arabic scales. And these Japanese pentatonic scales are beautiful, but nobody ever told me that you couldn’t create a chord progression out of a pentatonic scale because they are only five notes. So I took the Kumoi scale and built a chord family, maybe four chords. Then I played the scale over the chord progression. Larry said, ‘Well, you can’t do that.’ The reason this is interesting is that this parallels so many things in my life, things that I didn’t know I couldn’t do, so I did them. I played it for Larry, and he just said, ‘Wow. But just so you know, you’re not supposed to be able to do that.’ I think I was 21 at the time.”

His other big influence early, his first live performance, was with his church choir, one that would tour around the world when he was a teenager. Later he would add guitar to the piano accompaniment. Always he would sing. “That is real music to me,” he says with obvious enthusiasm. “It’s one of the greatest things I’ve ever done. And I still do it with the Youth Gospel Group in Santa Barbara. We recently did a benefit concert for a young guy with a heart problem. We did ‘Lean on Me,’ me, a Wurlitzer and 40 kids.”

The music, naturally, led to recording, most often in parallel, and he progressed from 4-track in his bedroom to bringing a band into Hollywood Sound Recording and getting his first real taste under the tutelage of Ross Pallone. There was an API console, Neumann mics, outboard gear; it was a place, he says, that felt strangely familiar from the minute he walked in the door. He was made a staff producer soon after, and he figured out the studio. In the ’80s, he would approach mastering with the same zeal.

“Chris and I met back in the 1970s, and he struck me back then as a guy who was very eager to learn and to be in the studio as much as possible,” says Michael McDonald. “He was one of the first guys I knew who made his own record, released it on his own label, and worked it on radio. He didn’t seem to let any boundaries stand in his way. He’s one of the few people I know who has personal experience in nearly every facet of the music business. And he’s good at what whatever he does—a good songwriter, a great guitar player, and a great producer, too, with a very distinct and unique style of producing. He sees the genius in simplicity. He breaks things down to the simplest form and then works with that. In the ’70s we would mike everything that made a sound, mics up our nostrils in the studio. Chris always saw that those records were great, but not because they had all those mics, but that they had a few placed right to capture the sound.”

As we went to press, Pelonis was finishing the last mixes on a Jeff Bridges and the Abiders live record, recorded on the road over the past two years. He’s there on lead guitar, he’s the musical director of the band, and he’s the engineer.

STUDIO DESIGN

It wasn’t a giant leap from being a musician and artist to his current livelihood as studio designer and speaker manufacturer. He had a problem he needed to solve, and it was in his own studio. By the early 1980s he saw the changes coming in the audio industry with computers and processing power and lower-cost, professional gear. He just hadn’t considered the room. He got a space, bought an early Akai 12-track, set up some speakers, and found that it sounded dreadful.

“I spent five years of building and tearing down my own space, 15-hour days,” he recalls. “I finally realized that the low frequency was causing all the trouble and was the most difficult thing to address. So I hyper-focused on that and spent years prototyping and building these low-frequency devices and understanding how low end acts in a small room—where it typically causes problems and will accumulate. I finally came up with something that seemed to clean it up, and everybody wanted me to build them for their studios. I was making records but not making money at that time.

Jeff Bridges, captured backstage somewhere in Northern California, in 1/1200th of a second, by Pelonis, seen in the mirror taking the photo.

Photo: Chris Pelonis

“So I took these absorbers to have them tested in an accredited lab,” he continues. “The guy told me that it wouldn’t do anything in the low frequencies, and asked if I was sure I wanted to spend the 2,500 bucks. Again, something I wasn’t supposed to be able to do. When I came back, he got wide-eyed and said it was not like anything he had seen. It took all the lows out. That became this thing called The Edge, which I eventually patented and trademarked and sold for years. But all I really wanted to do was build a few and carry on with my recording.”

Helping out a few friends turned into consulting on studio fixes, and today he’s more than 600 studios in to his design career; he never even knew he was a designer until he was nominated for his first TEC Award and found there were others out there. He learned CAD on his own, 3-D rendering, and today he builds virtual models for clients and contractors. Although not licensed, he taught himself architecture, electronics and other disciplines necessary for acoustical design. His overriding philosophy is to listen to clients, to spend time with them, and to give them what they want, while helping to guide them to what he thinks they might need. Often they aren’t the same thing.

Over the past 30 years, Pelonis has designed personal studios for individual artists, commercial facilities, mastering suites, film stages and more than 75 rooms for Sony PlayStation Studios, all over the world. He’s fixed back walls for friends and he’s designed home theaters and listening spaces. He’s made a noisy but popular bar-brunch spot in Encinitas sound good, so people can still talk yet feel the energy. He knows acoustics and how sound waves behave in a space.

SPEAKERS

“If anybody talks to me for even 15 minutes, they will hear me talk about Chris Pelonis’ speakers.” —David Crosby.

For the entire time Pelonis has been designing studios, he has also been acutely focused on the interconnection between room and speaker. He started working in studios in the 1970s, with mains that were big-sounding but far from accurate. The studios of the 1980s, then, were populated by near-fields, from a hi-fi version out of Mitsubishi, to the ubiquitous Yamaha NS-10s, to Auratones. When Tannoy came out with its 10-inch Super Gold, later with a modified crossover by Doug Sax and Steve Hazelton at The Mastering Lab, he started paying more attention.

“They were on the right track with the phase response of the tweeter and woofer being centered in the same position,” he says today. “As you get off-axis, the high frequencies and low frequencies arrive at basically the same time and you don’t get the phase anomalies. It’s very tricky to get the tweeter and woofer to marry when they are living together. When you have a true dual-concentric—which is different than a co-ax, which basically has a tweeter hanging inside a woofer—the woofer and tweeter become one, and the woofer actually becomes a continuation of the waveguide of the tweeter. Tannoy was doing that, and I started working with them to build a main monitor.”

The relationship with Tannoy led from Pelonis Signature Series mains on down to a 15-inch, then 12-inch, then a 10-inch model, which he designed specifically for Sony PlayStation. Artist/producer Jimmy Messina, a friend and colleague in the Santa Barbara area, was rebuilding his home studio when Pelonis brought over an early version of his PSS 112, the 12-inch. Messina still mixes on them today. In fact, he’s one of the people who helped drive Pelonis to develop his newest version, the Model 42, a 4-inch powered monitor that he builds and markets on his own. Messina, it seems, wanted a more plug-and-play portable version of what he had with the 12s.

“When Chris was building these 4-inchers in his garage, we went back and forth from his place to my studio, and finally he got them done,” Messina recalls. “He brought the final prototype over and I thought, ‘Oh my God, they sound like the big speakers I have right here.’ Chris said, ‘That’s the idea. You can go back and forth and not really have any issues.’ That’s where I relate to Chris. He’s very creative on the right side of his brain, and then he can put all the pieces together. He’s also a producer and an engineer, and that resonates with me.”

It’s one thing to develop a line of speakers with a big company, quite another to do a new model on your own. That was never his intent, to be a manufacturer. The prototype he had built would have had to retail at $3,000 a pair for him to even approach breaking even. He knew nobody would buy them at that price, with so many lower-cost alternatives out there. He partnered with an OEM manufacturer and was exacting in his details and demands to get the final package close to the prototype. He abandoned the MOSFET amp for Class-D, though he kept power outside the cabinet because he doesn’t think sensitive electronics should be housed in a vibrating magnetic enclosure, and he finds it more convenient to have a nearby power station and run speaker wire, whether for installation or for portability.

He was near maniacal in his testing of every single piece in the chain—amp, processor, converters, crossover, power, the ins and outs. He drove the engineering team crazy with his A-B switching. They go up to 35k Hz and down to 70 Hz. “People want to slam them, but you don’t need to mix that loud,” Pelonis says. “They almost work like a pair of headphones; you can take them anywhere. Not a lot of sub lows but there is a perfectly matched sub, the Model 42LF MKII.” Today a pair retails for $1,299. At a normal cost-to-price ratio, he should charge a lot more.

“You hear a Pelonis speaker and it’s just very true,” Bridges adds. “When you are listening to music, especially music you are making, you want to hear a very accurate sound. You don’t want it to be colored and sound sweet on one system and not sweet on another. You want it to be as accurate a reproduction of what you’re making as can be. It turns out he makes these incredible speakers.”

THE OTHER STUFF

Chris Pelonis is not unique in any one singular audio talent. There are great musicians, vocalists, engineers, songwriters, producers, studio designers and speaker makers out there. It’s more about how he brings them all together, and how he integrates the same ethic in his personal life. He’s been involved in martial arts since he was 12 years old, studying consistently for 25 years, with an emphasis on Kung Fu San Soo, where he took it beyond the combat training and found the inner patterns to train mind, body and soul, and to attain focus. He reached the discipline’s highest level, and he learned that there are no shortcuts to getting good at something like kung fu, guitar or studio design.

A view from the Western Gateway to Heaven.

Photo: Chris Pelonis

Lately, photography has re-entered his life, and he’s pursuing the art and technology as doggedly as he has everything else. He shot film and had his own dark room as a teenager, but became disillusioned with early digital cameras. Then on a trip to Japan for Sony a few years back he began reading about Foveon sensors, owned by a company called Sigma, which made cameras.

“I bought a Sigma camera while I was there, and I went around Japan and started taking pictures,” he says. “I thought, ‘God, this looks like film! This was a very early version of it, but there was a film-style character that was satisfying. The Foveon sensor basically exfoliates the same way as film. It does a true color separation so there are three colors per pixel instead of one. That made sense to me. I got excited about shooting again. Photography came alive again, just like music did when digital recording got to a certain point.

“Just like with speakers, I want that truism,” he says. “The cameras I have now can capture that, but there is also an ability to be abstract and artistic and creative and obscure.”

He’s a man of faith, and he talks freely of his Christianity without proselytizing. He attributes his bent to help those less fortunate to that faith and his family. “There’s a grace and an aesthetic that runs through Chris’ work and his life, whether it be making music, designing studios or surfing,” says his neighbor and dear friend Jackson Browne. “There is a fine-tuning, and a balance, that I marvel at and can only hope might instruct me.”

He is many things, but to truly understand who Chris Pelonis is, it helps to visit his home and family and friends at Hollister Ranch, a small but tightknit community on a 14,500-acre working cattle ranch west of Santa Barbara. That’s where he finds his center, on his own ranch with 10 horses, chickens, goats, dogs, cats, an occasional mountain lion, and his loving family of wife, Kim, and children Christian and Jesse.

“This is the most amazing community I’ve experienced,” he concludes. “It’s very eclectic, there’s a lot of controversy. It’s diverse, with a lot of people with a lot of different ideas. But there’s a camaraderie here that I haven’t found anywhere else. And I seem to fit here. The Chumash Indians call it the Western Gateway to Heaven, and if you look at Point Conception as sort of this angry male energy coming from the north in the winter, and then on the south side you have the calm—where those two meet is further west than anywhere in California. It’s those two meeting as a birth, coming together, creating a life, which is what conception means. There’s a lot of stuff happening here that you can’t necessarily see, but I get a lot from it. My feelings, my thoughts. So much happens when I’m here.”

A few of the many studios Chris Pelonis has designed, from top: Archon, Cider Mountain Tracking, Jeff Bridges personal, On the Path, and Sony Computer Entertainment, San Mateo, Calif.

Photo: Chris Pelonis