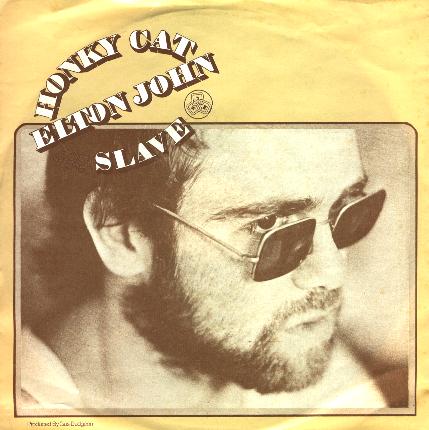

How do you choose a classic track out of Elton John’s vast collection of greatness? You gotta go for the unexpected, I guess, and 1972’s “Honky Cat” stands out in that way. Not that the great songwriting pair of Elton John and Bernie Taupin was ever predictable, with such compositions as “Rocket Man,” “Bennie and the Jets,” “Crocodile Rock” and on and on, but this one definitely comes from another ZIP code. With its funky New Orleans groove, John tickles the keys while horns punctuate the track, and all you can say is, “That’s the cat.”

“Honky Cat” was the second big single off Honky Château, reaching Number 8 on the American charts, proving that John’s decision to record with his live band—bassist Dee Murray, drummer Nigel Olsson and brand new member, guitarist Davey Johnstone—was a good one.

“Honky Cat” was the second big single off Honky Château, reaching Number 8 on the American charts, proving that John’s decision to record with his live band—bassist Dee Murray, drummer Nigel Olsson and brand new member, guitarist Davey Johnstone—was a good one.

The album was John’s first of three cut at France’s Château d’Hérouville, engineer Ken Scott says, originally for monetary reasons.

“There was a strange British tax law at this time which stated, as I understand it, that if recordings and/or music written took place outside of the UK, then all monies earned from outside the UK would be taxed in the country of recording and/or writing,” Scott says. “France had much lower taxation rates at that time, and so the decision was made to write and record there. How the Château d’Hérouville was discovered, I do not know. I know that the Grateful Dead had spent time there, but I’ve never heard of any other artists, other than French artists, who had recorded there prior to us.”

This was going to be Scott’s first full album with John. “After the recording of Madman Across the Water, the wonderful engineer Robin Cable, who had recorded all of Elton’s earlier work, was in an extremely bad car accident,” Scott recalls. “So bad that we were unsure for a while if he would come through it. Commerce always wins out, and the album had to be mixed, regardless, and as I had worked with Gus Dudgeon, the producer, previously at Abbey Road, I was put on the mix sessions.”

When it came time to hire an engineer for the follow-up album, which became Honky Château, Scott was called again.

Scott says the perk of recording at a residential studio was “total submersion.” Pre-production was done in the dining room.

“That’s where I first heard everything,” Scott says. “As an example, Bernie Taupin brought a stack of lyrics down to breakfast for Elton to go through as he ate. Elton would then go over to the piano and work on the lyrics he liked, on one occasion leading to ‘Rocket Man’ in 10 minutes. Then the band would work on the arrangement.”

Davey Johnstone recalls those dining room sessions as well, sitting in a semi-circle with a tiny setup of guitar, bass, drums and piano, while the crew was setting up in the studio.

“When Elton was writing the song ‘Honky Cat’ to Bernie Taupin’s lyric, I picked up my banjo, thinking, ‘This might be cool on this song,’” he says. John ended up agreeing, and apparently so did Joni Mitchell. Johnstone says he was bowled over when he met Mitchell and she told him how much she loved the banjo on that track. “It’s interesting to note that banjo was my main instrument before joining Elton,” Johnstone adds.

Scott was excited about recording somewhere different, which he said had a few “small hiccups.” One was the language barrier, and another was that there were no isolation booths. They had to be constructed.

“Gus had some carpenters put together a box the shape of the piano and about three feet higher, which went over the top, and there were two holes for me to put the mics in through,” Scott recalls. “I used a Neumann U 67 on the low end and a Neumann KM 56 on the high end.”

Another issue was the board. Scott remembers it as “a very strange custom-made job” with a learning curve. The Internet suggested it was either an MCI or the Dutch-built Difona. Scott says he’s inclined to think the Difona makes more sense.

“There were Lockwood monitors,” he says. “We used Dolby A, we recorded 16-track, but I don’t remember the make of the machine. Scully is certainly a possibility.”

Scott says everything was recorded the same way: piano, bass, drums and sometimes a guitar all at once. Then the overdubs would begin. “Once we had the master of the basic track, Elton overdubbed a Fender Rhodes,” Scott says.

The horn players were locals. “The mics would have been Neumann U 67s—obviously my favorite all-around mic—on the saxes and Coles 4038s or some other ribbon on the trumpet and trombone,” Scott says.

At the mention of “Honky Cat,” and questions about the drums and period at the Château, you can feel the smile across the miles as drummer Nigel Olsson responds via e-mail while in Australia on tour with John.

“Every moment at the Château was a brilliant time in my life,” he wrote. “When I first heard ‘Honky Cat,’ it sounded like a British pub song, a sing-along kind of thing. I was using a mishmash of Premier drums, my sponsor at that time, which included a couple of concert tom-toms tuned way down low. As the recording room was kind of small and we were all playing at the same time (the way recording should be done), we built a box out of tall baffles around me and the drums for separation. I was totally closed in. I couldn’t see the rest of the lads at all. In fact, it took me five minutes to get in and out. Very low tech, but it worked great. I think we cut the track in two takes. To this day it’s a fun song to play live, and it gets a great reaction from the crowd. One more thing about that studio was they had a live echo chamber, which inspired my huge drum sound from then onward. I love echo and reverb in my headphones, and I always have it onstage in my mix. Life as it should be!”

Scott says the mic on the bass drum was probably an AKG D12. He says he probably used a Neumann KM 56 or KM 54 on the snare, and for overheads, probably ribbons.

“On the toms, I have no idea,” Scott says. “Nigel was using concert toms at that time and the mics were placed up inside them, so I’m sure they weren’t my usual U 67s, which means I just don’t know,” he laughs.

On John’s vocals, Scott is also unsure. “I can’t remember if I used a Neumann U 67 or an AKG C12 for his vocals, but it was always the same mic,” Scott says. “Elton got bored in the studio. He would of course be there for the basic tracks and any overdub that was specifically him. Other than that, he was rarely around. Same went for the mixes. He only came by for a final play-through. He totally trusted Gus and the band so he didn’t feel the need to micro-manage.”