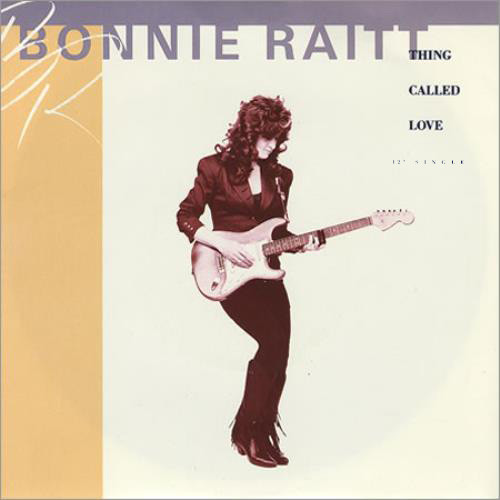

When I call engineer extraordinaire Ed Cherney about the recording of Bonnie Raitt’s commercial breakthrough, “Thing Called Love,” the first thing he says is, “Isn’t that a little recent for a ‘Classic Track’?” “Dude,” I said, “it was recorded 22 years ago!” He got a laugh out of that; it does seem like it was just yesterday in some ways. But it was cut in 1989 and was a keystone of her album Nick of Time, which won a Grammy for Album of the Year in 1990 and sold more than 6 million copies in the U.S. alone.

Raitt’s success was a long time coming. The daughter of Broadway singer John Raitt, Bonnie Raitt started playing guitar at an early age, but didn’t turn serious about music until she was living in Cambridge, Mass., and going to Radcliffe College (Harvard’s all-girl “sister” school) in the late ’60s. It was in Boston that she met and befriended Dick Waterman, who had been deeply involved in the early ’60s Cambridge folk scene and “blues revival,” putting on shows by recently rediscovered bluesmen like Bukka White and Mississippi John Hurt, personally “finding” the long-retired Delta singer Son House (in Rochester, N.Y., of all places) and later starting a booking agency that handled those three and such greats as Skip James, Lightnin’ Hopkins and Big Boy Crudup. Raitt immersed herself in the blues, learning what she could from these living legends, and soon was opening for them on occasion. With a powerful voice that could be gritty one second, delicate the next, and serious guitar chops (especially on slide), the beautiful redhead was a striking and different artist, interpreting traditional blues and folk in her own way.

She dropped out of college to devote herself to music full-time, and by 1970 had been signed by Warner Bros. Records. Her self-titled debut came out in 1971 and was a critical success, if not a commercial triumph. It, and her next album, Give It Up, established a formula of sorts, offering a mixture of blues by the likes of Robert Johnson, Fred McDowell and Sippie Wallace; tunes by up-and-coming songwriters such as Jackson Browne, Chris Smither and Eric Kaz; and a sprinkling of a couple of her own compositions in the mix. Later albums championed writers like John Prine (“Angel From Montgomery” was an FM favorite), J.D. Souther, Karla Bonoff and many others, and she earned a reputation as a truly dynamic and personable live performer, as well. From her earliest days, she was politically active, giving her time and energy to many causes. Her first minor hit was a bluesy reading of Del Shannon’s “Runaway” in 1977 (on Sweet Forgiveness), but she was unable to follow it up to Warner’s satisfaction, and in late 1983, Warner Bros. abruptly dropped her (along with several other “prestige” acts), even though she had recently completed an album at tremendous expense.

Raitt says this was a particularly low time for her and that both her health and personal life were in bad shape, but during the next couple of years, she managed to pull everything together, and she continued to tour successfully and play a number of major benefits. Raitt signed with Capitol Records in late 1988 and was soon in Ocean Way (L.A.) Studio 2 working with producer Don Was and engineer Cherney on Nick of Time. She had met Was—who was leader of the quirky but cool band Was (Not Was), and branched into production with albums by Carly Simon and The B-52s—when he produced a version of Raitt singing “Baby Mine” from the film Dumbo for the hip 1988 album of Disney film song remakes called Stay Awake. Nick of Time marked the first time Cherney worked with either of them, and it proved to be a turning point in his career.

Cherney had cut his teeth as an assistant engineer for Quincy Jones and Bruce Swedien (among others), but by the early ’80s was mostly recording and mixing jingles, which he says gave him invaluable experience working fast and in different music styles. He landed a Delco car-battery spot featuring music by Ry Cooder, which led to recording and mixing Cooder’s entire Get Rhythm album. Cherney followed that with a disc for Cooder’s buddy David Lindley, the superb Linda Ronstadt–produced Very Greasy. “I knew that Bonnie was going to be doing a record,” Cherney recalls. “I’d been a big fan of hers for a long time, and at that point, having done Cooder and Lindley, I was really into slide guitar and also listening to a lot of blues. So I lobbied everyone I knew that knew Bonnie and pleaded with them to tell her that I was the perfect guy for her.” Evidently, Cherney’s plot was successful because he soon got a call from Was and, after a lunch with him and Raitt, landed the gig. “We laughed the whole meeting and I just fell in love with both of them,” Cherney says.

This month’s “Classic Track,” “Thing Called Love,” was written by John Hiatt and originally appeared on one of his most popular album, the 1987 Bring the Family (which featured Cooder on guitar). Joining Raitt at Ocean Way for her version of the driving rocker was her regular touring band at the time: bassist Hutch Hutchinson, drummer Ricky Fataar and guitarist/harmony singer Johnny Lee Schell (augmented by Tony Braunagel on percussion). The Nick of Time album in general is more stripped down and economical than some of Raitt’s previous efforts, which frequently featured dozens of different players and singers, and “Thing Called Love” really feels like a small band just playing—which is what it is, Cherney says.

“It was live in the studio,” he says. “As I listen now, I remember we overdubbed Tony’s percussion. But I’m sure the vocal take was a combination of live and maybe a couple of overdubs from other passes at it. Bonnie liked to sing and play out in the room with the band. I think the first time we set up to cut, I put her in a booth and it just didn’t swing and she wanted to be out there. So that’s when I discovered [Shure] SM7s and [Electro-Voice] RE-20s on her vocal. The RE-20, in particular, was pretty clear-sounding and it resembled a large-diaphragm condenser microphone in a lot of ways, but it’s got incredible rear and side rejection so you could put her in the room with the band and not have to even put baffles around her, though I think I did probably put one up. But she could be with the musicians, and everyone could feed off each other, hear each other, see each other. And when you’re close to the drums, you feel the drums and I think you sing and play a different way, rather than being isolated in a booth somewhere.

“Johnny [Lee Schell] was out in the room, too, and I put some goboes around him because he was playing acoustic guitar. I probably used an [AKG] 452 on him; that’s really directional. He did his harmony vocal right after that and it was easy; he’d been singing with her forever, and that kind of harmony is part of his DNA so it was no problem. But a lot of Bonnie’s vocals on this record were for the most part live.”

For Fataar’s drums, “I had [AKG] C-12s overhead and probably a [Shure] 57 on the snare with a [Sennheiser] 441 underneath. At that time, I’d just gotten these B&K 4011 microphones and I’m sure I had that on the hi-hat. For toms I might have been using C-12As, and the kick drum was probably a [Neumann] FET 47 and a [Sennheiser] 421. I had [Neumann] M50s up in the room fairly wide, and I ended up not using much of them. But I do remember I had a [Neumann] 87 in omni about 10 feet in front of the drums, about six feet high, and I compressed [with a Fairchild] and EQ’d the heck out of that. That was what we used for drum ambience.” Hutch’s bass was recorded with a DI and a FET 47 on the amp, probably without any EQ or compression; Raitt’s slide, which she also played live on that track, had a 57 close on the amp and an AKG 414 “back off it a little.” Nick of Time was recorded analog on an Ampex ATR-124 machine through a 40-channel custom Neve RCA 8028 console, “one of only two built with Class-A discrete electronics.”

The album was mixed at the Record Plant in what was then called Studio 4 (now SSL 4) on a Neve VR. “A bunch of the songs on that record were pretty easy to mix, but I struggled with ‘Thing Called Love’ a bit,” Cherney reflects. “I think I went back to it probably three times. It needed to sound real and organic, but it also needed to stand up and kick you in the ass. Bonnie and Don were patient while I tore my hair out until I felt I had it nailed.” He used minimal effects: “Some slap on Bonnie and on Johnny Lee, and then a couple of the plates at Ocean Way. I probably used two EMT 140s—one short and bright, and one with a 2-second decay with probably 120 ms in front of it.”

The finished track simmers with a rawness and intensity that fits Raitt’s voice and slide guitar perfectly. Though not a smash hit in the sense of being a successful single, “Thing Called Love” was gobbled up by FM radio across the country (it reached Number 11 on Billboard’s Mainstream Rock Tracks charts) and was an immensely popular video on the still-rising VH-1 network—having Dennis Quaid at his cutest in that video no doubt helped. Buoyed further by the success of Raitt’s moving, self-written ballad “Nick of Time,” the album quickly became the artist’s biggest seller by far and really went into the stratosphere when it won three Grammys (Album of the Year, Best Pop Vocal Performance Female and Best Rock Vocal Performance Female)—it hit Number One right after that. It was, Cherney says, “life-changing.”

Raitt, Was and Cherney would have even more success with the 1991 album Luck of the Draw (which contained the smash “Something to Talk About”) and enjoy a three-peat with Longing In Their Hearts, which hit Number One in 1994. Was and Cherney won individual production and engineering Grammys, respectively, for their work that year. The duo’s productive partnership also included albums with Bob Dylan, Iggy Pop, Neil Diamond, Bob Seger and the Rolling Stones. Raitt has reduced her output in recent years and tours less frequently, but still can be counted on to make fine albums, put together a first-rate band and show up when a good cause needs a helping hand.