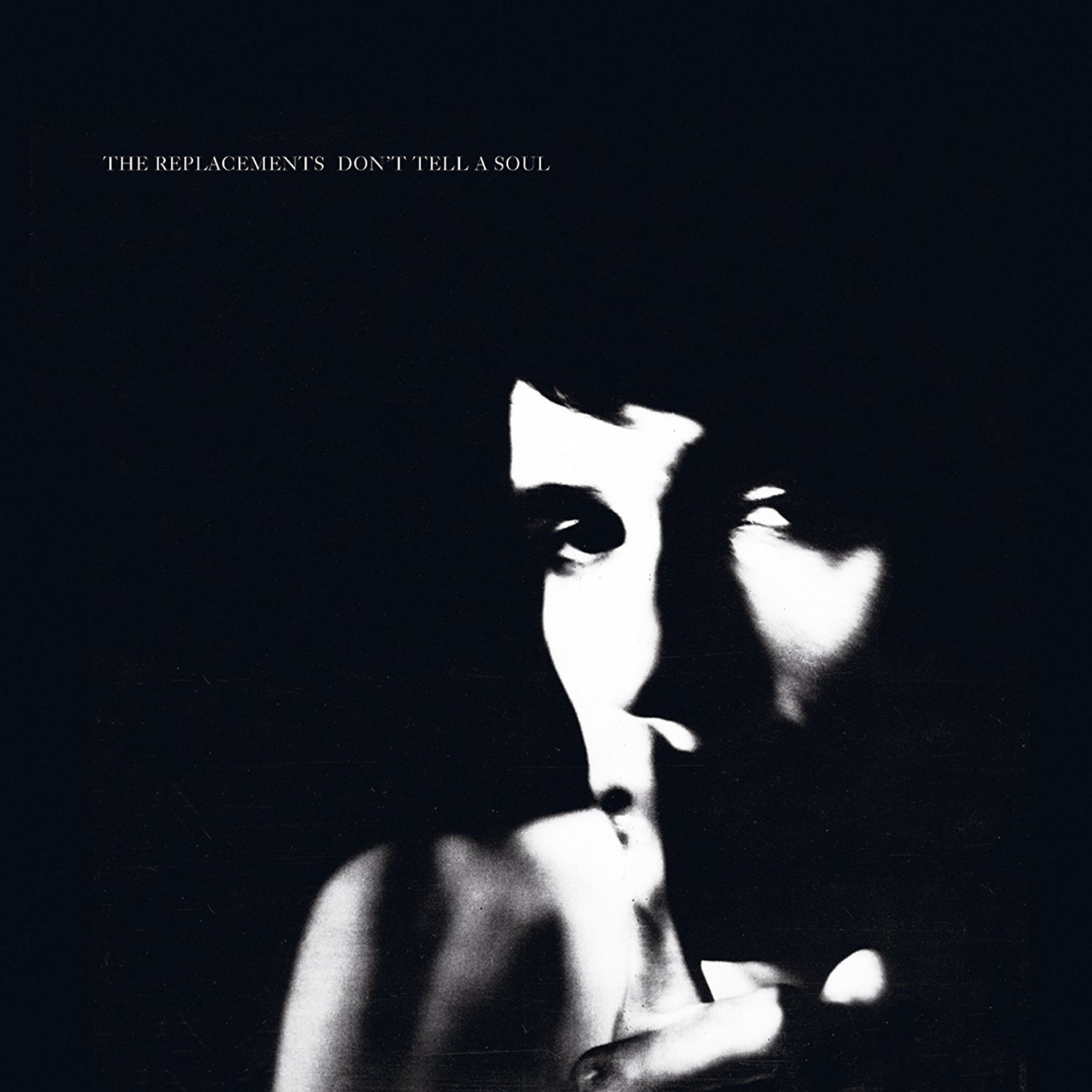

We talk a lot about “paying your dues” in the music business. Producer/engineer Matt Wallace paid his back in 1988 when he produced The Replacements’ raw, charming and clever album Don’t Tell a Soul. “I was basically hazed for most of that record,” he says.

Wallace had relocated to Los Angeles from San Francisco in January of that year. “I was hitting a wall in the Bay Area,” he says. “I kept making demos for bands that would get signed, but ultimately I couldn’t get hired because I wasn’t a big enough fish in the pond.”

Wallace signed on as a staff A&R rep/producer for the Slash indie label, where one of his early claims to fame was producing a song by the so-called New Monkees.

“Warner Brothers was working on a Monkees reboot,” Wallace explains. “They had four guys who were ready for TV and a bunch of writers. Obviously, it never really broke through, but I got to know the people at Warners. Then I heard The Replacements were making a record, and I started calling and saying, ‘Hey, I’m a fan and am interested in working with this band.’ But they were like, ‘Well, Tony Berg’s doing the record, sorry.’”

Berg turned out to be one of three producers who would work on Don’t Tell a Soul. “They spent three or four weeks in Bearsville Studios,” Wallace says. “They did some pre-production. They started recording and were on their way to making a record, and then—it depends on who you speak to—he was either fired or he quit. Apparently, someone got into a fistfight with Tony Berg—typical Replacements shenanigans.

“After that, they started working with Scott Litt, but I heard they ended up duct-taping him to a chair, and he was like, ‘Nope.’ Meanwhile, I was still calling Warner Brothers every couple of weeks.”

Wallace believes it was ultimately his persistence and his quirky resume that won him the gig. “They wanted a successful record, but they didn’t want somebody who had ‘sold out’ as a producer,” Wallace says. “At the time, Faith No More had a successful song, ‘We Care A Lot,’ that I produced, but they hadn’t really broken through yet. I actually think that I got hired because Warners told Paul [Westerberg] that I produced the New Monkees. It’s almost like sitting in a bar and saying, ‘The next guy to walk in the door is going to be our new drummer.’ That’s what they do: ‘Oh, he produced the New Monkees? That’s our guy.’”

Classic Track: “Epic,” Faith No More

Before the band members committed to working with Wallace, the label arranged a phone call between the producer and frontman Westerberg. “We talked about music,” Wallace recalls. “He said, ‘We drink a bit,’ and I said, ‘I’m totally aware. I’ve seen you guys. I don’t drink at all, so we’re going to get along famously.’”

And so Wallace became The Replacements’ designated driver.

Sessions on Don’t Tell a Soul began in Cherokee Studios in Los Angeles, where Wallace, Westerberg, guitarist Slim Dunlap (who had replaced original guitarist Bob Stinson in 1986) and assistant engineer Mike Bosley, who the band knew from Minneapolis, did some pre-production on the song “They’re Blind.” Later, drummer Chris Mars and bass player Tommy Stinson joined for further pre-production at the nearby SIR rehearsal facilities. Then the project moved into Cherokee’s A room, which was equipped with a Trident A-Range console and Studer A800 tape machines, and live tracking began.

“This is part of The Replacements’ story, for better or worse,” Wallace says. “The band would like to drink, and they would say to our engineer on the album, John Beverly Jones, and me, ‘You should drink. If we all drink, then everyone lets down their guard.’ And Bev Jones said, ‘I’m not going to take part while working, but we can go out after work on Wednesday.’

“So, we worked Monday, Tuesday, and all day Wednesday, and then we went out after work to the Rainbow Room, and lots of shenanigans happened there. Tommy wrote with magic marker on my pants and my shirt, and then I had to magic marker him, and Slim threatened to beat me up. He jammed his face against mine and told me he was going to kick my ass.

Producer Matt Wallace Works with 3 Doors Down on “Us and the Night,”

“The next day, tracking was supposed to start at noon or so, but Bev Jones didn’t show up until 4 p.m., and I could tell the moment he walked in, that was it. He quit the project. These were sessions where Tommy splintered a Thunderbird bass and Paul was lighting $100 bills on fire. It was basically a somewhat contained circus with really, really talented people involved.”

Wallace then became the engineer of record on the album, along with Mike Bosley, but because Jones had set up the sessions, Wallace doesn’t remember all of the recording chains. Here’s what he recalls: “Basic tracking was pretty much live. It was a well stocked studio. We were using 1176s and LA 2As, and certainly using the board and the usual complement of microphones: [Shure] 57s and [Sennheiser] 421s on amps. Sometimes we used Coles [4038] mics.

“I know that at Cherokee I learned one of my biggest lessons with Paul and the band. We’d just finished a guitar overdub, and Paul said, ‘I want to do the vocals now,’ and I said, ‘Great, give me five or ten minutes, I’ll set up the mic and get a headphone mix going.’ I got out a [Neumann] U47, I put a pop filter on it, got the headphone mix right, and I said, ‘Okay, I’m ready to go,’ and he said, ‘No. I lost the vibe.’

“With the Replacements, it was always a brutal battle between catching their energy, spirit and their vibe, while also capturing things technically to sound good as they could. They didn’t want to have to deal with the encumbrances of the studio process, and that was demonstrated time and time again.

“On ‘I’ll Be You,’ for example, Paul played a guitar part, and I said, ‘Oh, man, that’s a great guitar part. Let’s tune up your guitar and play it again and maybe play a little more with the beat—don’t lean so far forward. And he was like, ‘Oh, I forgot the chords,’ which was like, ‘F—k you. I’m not playing it again.’

Most of Westerberg’s lead vocals, including the track for “I’ll Be You,” were done after the sessions at Cherokee ended. The team next decamped to Capitol Studios to take advantage of the studio’s famed chambers and historic vibe.

In the Studio and On the Road with Blues Traveler

“Their echo chambers were built under the parking lot and they were so good that Capitol used to rent out time to studios around the country via ISDN phone lines,” Wallace explains. “Studios would send their signal to the chambers in Capitol, where they’d have a couple of mics set up, and then Capitol would send the signal back over another pair of phone lines, so anyone could access these chambers while mixing. They were gorgeous-sounding and Paul was really enamored of them.

“Also, he loved the Frank Sinatra records that were recorded there. While we were doing the vocals, instead of saying, ‘Can I have a little reverb?’ he’d say, ‘Put a little Frank on my voice.’

“We did the vocals on ‘I’ll Be You’ there. There weren’t too many moments when I had any sway with getting something across, but that was one where I can pinpoint exactly what I did that changed the song: When Paul got to verse three, at first he sang it an octave down, and I said, ‘What if you went up an octave here? I think you can handle the range, and it just might propel the song forward and give it a sense of urgency.’ And sure enough it sounds great, and it has this amazing momentum and energy.”

Wallace isn’t sure whether Westerberg sang into a Neumann U47 or 67 at Capitol, but he does recall using a UREI 1176 on his voice. “That was to capture some of the peaks, and sometimes I would have the 1176 on the front end with a 4:1 ratio, and then an LA2A after it to give it some tube warmth.”

Further overdubs, as well as significant editing, were done in the band’s hometown of Minneapolis, at Prince’s Paisley Park facility. It was there that Wallace addressed the band’s timing issues. He used the delay in a Publison Infernal Machine to adjust each guitar or bass part.

“The band would leave for the day and I’d stay late,” Wallace says “Starting with the bass, I would go song by song, bar by bar, and delay the part by 20, 30, 40 milliseconds and then re-record it on an adjacent track to match the drums. Then I could erase the original bass track, take one guitar and do the same until everything was in time. Unfortunately, that means those guitars and bass are two generations removed, but I had to put them in time.”

Don’t Tell a Soul was mixed by another then-recent transplant, Chris Lord-Alge, who had recently relocated to L.A. from New York. In 1988, Lord-Alge was ensconced at Skip Saylor Studios, where he mixed on a 56-channel SSL E Series board.

Interview with Chris Lord-Alge

Chris Lord-Alge’s Mix L.A.

“I didn’t know anything about The Replacements or garage rock. Each of those songs was quirkier than the other,” Lord-Alge says. “But when we got to this ‘I’ll Be You’ track, to me, it was the only song on the album that resembled a rock song for radio.”

Lord-Alge took the same approach to “I’ll Be You” that he has used to take songs from Pat Benatar, Tina Turner and others to the next level. “I wanted simple guitars, and bass, big vocals and gargantuan drums. I was cherry-picking the most straight-ahead guitar stuff and really pushing to keep it simple,” Lord-Alge says.

Much of the processing gear Lord-Alge used in the late ’80s will be familiar to those who have read about his more recent projects: Lexicon PCM 42, Sony DRE2000, AMS Ursa Major Space Station, Yamaha Rev 5, Roland SDE 3000.

Classic Tracks: Prince and the Revolution’s “Purple Rain,”

“I remember vividly that Saylor’s [Skip Saylor Recording] had a whole rack of APIs, too, and I was using those to get more aggression out of the drums,” he says. “I had either a TC 2290 or an AMS sampler running my snare samples. The whole time, Matt was trying to craft less slick and more garage-y, and I was going for big, in-your-face rock, and we would go back and forth. When I came across ‘I’ll Be You,’ I said, ‘I’m taking this one for me. This will get them on the map.”

In fact, “I’ll Be You,” became The Replacements’ biggest hit, rising to Number 51 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart and to Number One on the Modern Rock and Album Rock charts. And Matt Wallace was soon very much on the map as well. The next album he produced was Faith No More’s The Real Thing, which included the megahit “Epic.

“I’m proud that I was able to take The Replacements further than they had gone before,” Wallace says. “That was my goal going into it, to get them exposed to more people, because I was a fan. I’m still a fan.”