The story of the recording of “Blue” by LeAnn Rimes is one with many twists and turns, and has now become part of country music lore. Sometimes lost in the tale is that the heart of the story runs through the legacy of producer Norman Petty and his studio in Clovis, N.M.

Legendary country music DJ and songwriter Bill Mack had written “Blue” in the early 1960s for Patsy Cline. Unfortunately, Cline’s life was cut short in a tragic airplane accident before she had the chance to record the song. There were a few unsuccessful recordings of “Blue” in the years following, but the right voice for the song wasn’t found until Mack received a phone call from Marty Rendleman, a longtime friend who had just signed on to manage a then 9-year-old LeAnn Rimes. “I called my buddy Bill Mack,” explains Rendleman, “and I said, ‘Do you have any more Number One hits lying around,’ and he said, ‘Well, maybe for you…’”

Rendleman then presented the song to Wilbur Rimes, the father, and LeAnn, though Wilbur didn’t think the song was right for his daughter with its adult themes about love. LeAnn felt differently, and when she added the now famous yodel, Wilbur apparently changed his mind. “LeAnn made a really good country song a hit by putting that little yodel in there,” says Rendleman. When LeAnn entered the Norman Petty Studio in 1994, “Blue” was among the songs slated to be recorded for her debut album.

In the mid-to-late 1950s, Petty produced a string of monster rock ‘n’ roll hits with the likes of Buddy Knox, Jimmy Bowen and, most notably, Buddy Holly from his one-room studio at 1313 West 7th Street in Clovis. He continued his run with a group called The Fireballs and their Number One hit “Sugar Shack” in 1963 and their Top Ten recording of “Bottle of Wine” in 1968. In 1969, Petty moved his operations from that one-room studio to the Mesa Theater on Main Street, having purchased the theater in 1965 with the dream of turning it into the perfect recording studio.

In 1978, Petty took another big step and outfitted the Mesa with some of the most cutting-edge equipment available at the time. A major renovation took place, with the acoustics perfected, and Petty took delivery of an MCI JH-400 console, an MCI JH-24 multitrack and all of the latest effects units. Everything was in place; he just needed a superstar artist.

In the early 1990s, LeAnn Rimes was becoming a bit of a sensation in Texas. In Wilbur Rimes’ quest to bring his daughter’s voice to the world, he was introduced to a man named Lyle Walker. Walker and Minister Kenneth Broad had been longtime friends and advisors of Norman and Vi Petty and were among the people who helped Vi continue Norman’s work after his death in 1984. When Vi passed away in March 1992, Walker and Broad became the co-executors of the Petty estate, which included plans to keep the studio operational.

Walker hired his son Greg to manage the studio, and after a year or so getting up to speed and just beginning to record, the father told him that a young artist was coming in to record some demos. “We were just at the beginning of saying what’s here and what do we do with it, and my dad popped this little girl in our lives,” Greg Walker recalls.

Greg Walker turned to local guitar hero Johnny Mulhair for help. Mulhair had grown up in Clovis and, much like Greg, was in awe of Norman Petty. “Norman sure inspired me,” explains Mulhair. “Here’s a guy who’s made hit records and was very successful, and I got to thinking that’s what I want to do. He’s kind of a hero.”

Mulhair and his band Apple Glass Cyndrom had been among the very last recording projects that took place at Norman Petty’s 7th Street Studio when they recorded the psychedelic hit “Someday.” By 1994 Mulhair was a veteran musician also working as a producer and engineer. He was asked to assemble a band and to produce an instrumental demo session for Wilbur Rimes.

Wilbur Rimes liked what he heard and wanted to continue recording more demos, so a session was booked. Mulhair and his band met Wilbur and LeAnn Rimes at the Mesa Theater studio and started recording what they thought were demos. But, as Mulhair explains, it wasn’t long before Wilbur decided the demos should be a proper album. “We convened at the studio, and about halfway through the first day Wilbur said, ‘This is great, we’re gonna go ahead and do this album.’ So it wasn’t very far into recording the demos that we were making the album.”

For cutting the basic tracks, Mulhair had the grand piano on the stage of the theater. The drum kit was set up in the large isolation booth beside the control room with LeAnn in a smaller booth behind the control room. Mulhair would strum an acoustic guitar while working the MCI JH-400 console. The bass was run direct in the control room.

“We were all there in the room together; the only people we couldn’t see real well were LeAnn and the piano player, who was way down there on the stage,” Mulhair says. Most of the vocal overdubs were recorded in the larger drum booth, but on a few occasions LeAnn was put on the stage. For later sessions, where the original drum tracks were being replaced, the drums were put on the stage with the stage curtain drawn to reduce echo.

An RE-20 was used on kick and an SM57 on snare. Neumann KM 84s were used for overheads and hi-hat, with Sennheiser MD-441s on rack toms and Shure SM7s on the floor tom. The piano was picked up using a pair of Neumann U 87s. During bed tracks, Mulhair would plug his acoustic in direct, but for overdubs the KM 84 was used for guitars and other acoustic instruments. Muhair’s electric guitars were recorded direct through a DigiTech RP-1 effects processor. When it came to capturing LeAnn’s voice, a few different microphones were used—having access to the Norman Petty microphone collection allowed for many choices. In the end, a Neumann M 49 was picked but later in the project a U 48 was used, and on one occasion LeAnn sang through a U 47 FET.

The recording equipment was the MCI JH-400 console and the MCI JH-24 multitrack. As time moved on, much of the project was transferred to Alesis ADATs. “That first album we recorded all the basic tracks to that 24-track analog machine, and then we had such a maintenance nightmare that we had several people work on that machine and finally Greg said, ‘I’m going to buy some ADAT machines.’ So we dumped all that stuff off the analog machine into the ADATs, which had just come out at that time.”

In addition to the natural ambience of the Mesa Theater, an EMT Plate, and Lexicon 200 digital reverb, the studio’s hand-built echo chamber was the go-to reverb. Norman Petty’s secret weapon at his old studio on West 7th was his echo chamber, and his use of echo became legendary and set him apart from the competition in the 1950s. Naturally, when Petty built his new studio, he included a great-sounding echo chamber. “We used that echo chamber in the LeAnn sessions and in the mixing,” explains Greg Walker. “Johnny loved it; Wilbur loved it; everybody loved it. And Nashville…tried to emulate it. The art was not using too much.”

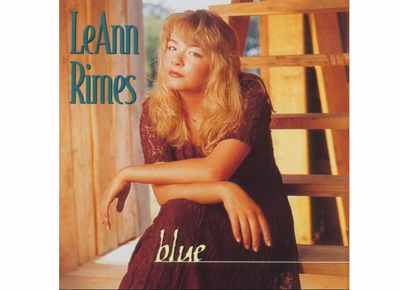

The initial recordings were assembled and released on LeAnn Rimes’ debut album All That in 1994. The album was released on the revitalized Nor-Va-Jak Records, a label that Norman Petty originally operated. The album soon became a huge local hit. Mulhair recalls how people reacted when they heard the song. “I would get a call from the truck stop here in Clovis with people saying, ‘Hey, where do we find that CD of “Blue” by that little girl.’”

As one would expect, a bidding war began among major labels, and Curb Records from Nashville was victorious. Mulhair was asked to start reworking some of the original recordings, as well as record new material. As demands for a finished product increased, sessions were set up closer to LeAnn’s Dallas home at Rosewood Studio in Tyler, Texas. Further sessions took place at Mid-Town Tone & Volume and Omni Sound in Nashville.

Altogether there were three versions of “Blue” that hit the market: the original version on the album All That; a reworked version that Mulhair produced in Clovis, released as the single; and a third version recorded in Tyler that was released on the full-length album Blue.

The song “Blue” reached Number Three on the Billboard Hot 100, and the album hit Number One on the Country Album Chart. In all, five singles were released from the album, and both “Blue” and “The Light in Your Eyes” reached the Top Ten.

For Johnny Mulhair, the success of “Blue” was potentially life-changing. He was nominated as producer of the year at the Country Music Awards in 1997. Many opportunities started coming his way, and a move to Nashville was on the table. In the end, much like Petty some 40 years earlier, he decided to stay in Clovis with his friends and family. Greg Walker decided to move on from the Norman Petty Studio, returning to the real estate business, and the doors of the Mesa Theater were closed. Mulhair resumed work in his own studio and quickly found himself a producer and musician in demand. “That sure was a big old shot in the arm and brought a lot of people into my studio,” he says. Today, Mulhair is still as busy as ever working from his self-named studio in Clovis. His latest project is an album by country singer Will Banister.

In many ways, the success of “Blue” was a fitting end to the Norman Petty Studio. Norman had built a recording studio fit for a queen in hopes of finding an artist worthy of recording. The only problem was that the artist wouldn’t arrive until almost a decade after his passing.