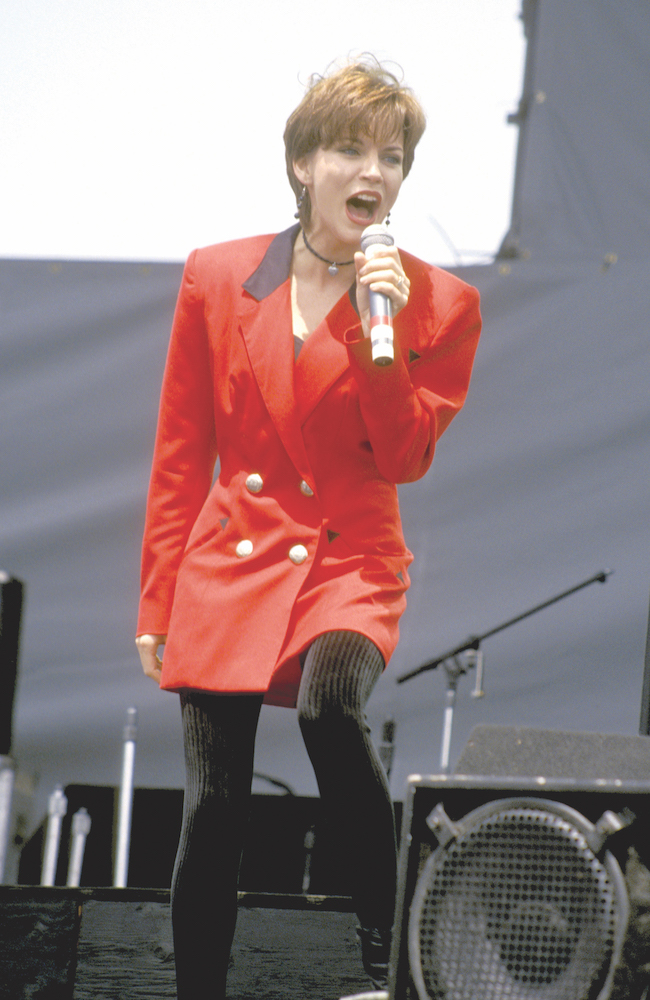

O.J. Simpson may have killed the chances of Martina McBride seeing “Independence Day” reaching Number 1. The song, which tackled domestic abuse in a poignant yet powerful manner, was released in May 1994, and Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman were stabbed to death on June 12 of that same year. While some radio stations believed the song was relevant, others banned it.

So a song that McBride so passionately delivered and which should have been a Number 1—the Country Music Association pronounced it Song of the Year—halted at Number 12 on the charts.

After hearing from her promotional team that there were multiple stations that would not play the single, McBride actually asked for a list of those music directors and called them. She remembers saying, “I’d like to have a conversation about this song. What’s the problem?

“They said, ‘We just don’t feel it fits on our radio station,’” she continues. “I remember saying, ‘But you’re talking about the O.J. Simpson trial every day on your radio station at noon and 6 p.m. and whenever you do your news. What’s the difference?’ Then I remember another programmer telling me, ‘When that video comes on and my daughter comes in the room, now I have to have a conversation with her about it.’ ‘Yeah, maybe that’s not a bad thing; maybe you should do that.’”

McBride was able to change some opinions, but ultimately 10 stations refused to play the song. From the moment she heard it, however, McBride never hesitated to record it. She says that she felt its power instantly.

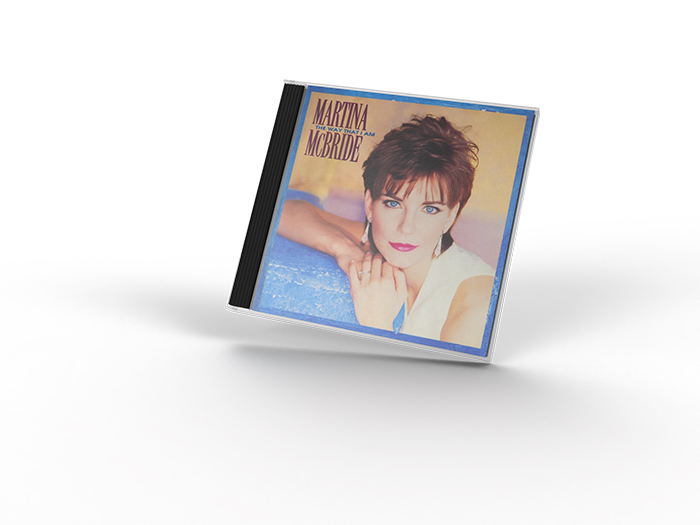

“Independence Day” was the third single from McBride’s second album, The Way That I Am, produced by Paul Worley, Ed Seay and McBride, and engineered by Ed Seay and Clarke Schleicher.

TRACKING AT THE MONEY PIT

Seay recalls that the basic tracks were done at The Money Pit in Nashville, owned by drummer Eddie Bayers, Jr., and his father Eddie Sr. He says they had done something of an overhaul on the studio a couple of years prior, which included the purchase of a Trident 80B console from Track Record Studios in Los Angeles, where he and Worley had been working on a project.

“This Trident 80B had an oversized power supply, or we bought a bigger power supply, just like a bigger engine for the console,” Seay recalls. “We got all the newest chip upgrades; the fastest, hottest-sounding console we could. And then we had a Mitsubishi X-850—that was big in town, but it didn’t sound that great. We got a guy to modify the analog circuitry, and it became the best-sounding X-850 I’d ever heard.”

The main room at The Money Pit was live-sounding, with linoleum floors and a wall covering called OSB that Seay describes as looking like chipboard. The room had a 14-foot ceiling and a vocal booth in one corner, with non-rectangular design throughout. The control room was expanded to include a medium-wood room, fairly live and splashy. Behind it, the acoustic guitars—in this case, Paul Worley and Bill Hullett—would set up to record. On both acoustic guitars, Seay used AKG 414s through an 1176. An office was converted into a keyboard area behind the vocal booth for the 9-foot Baldwin SD-10 Concert Grand piano, a Wurlitzer and a Twin reverb. Steve Nathan handled keyboard duties on the session.

Joe Chemay recorded his bass in the control room in front of the console, direct into an 1176. He had a view of drummer Lonnie Wilson, who Seay miked with a Neumann 47 FET on the kick drum into a GML preamp and an ADR Vocal Stressor. Seay placed a Shure SM57 on the snare, through a GML preamp into a GML EQ. On the hi-hat, he used an AKG 451; the overheads were AKG 451s. On the toms, Seay used Sennheiser 421s with an ADR E900 sweep EQ, which he describes as a “musical, but with very aggressive EQ which makes the drums explode.”

His room mics were Crown SASS-Ps—stereo PZM into UREI 1178S. “You put it out in front of the drums, and you get a perfect stereo image,” Seay asserts.

The Money Pit’s “secret weapon,” though, was the Sky Hook.

MAKING IT UNIQUE, POWERFUL

“I really haven’t seen other studios do this,” Seay maintains. “The ceiling in the main drum room was 14 feet high, and the Sky Hook was an SM 57 up at the very top of the ceiling, looking down on the floor. We put a lot of compression on it from a dbx 160X. It added so much explosiveness to the drum sound. It was so exciting, and to mix some of that in, to have a track of that, it sounded like you were in the room.”

It was just what the powerful song needed — for the listener to feel the implied explosion and fireworks of the subject matter.

Across the hall from the control room was the studio lounge, which doubled as the recording area for electric guitar. Brent Mason was miked with a SM57 into a GML pre to a Sontec DRE 202 compressor, then GML EQ. “It was a real suck-and-blow compressor, Seay explains. “It made up a lot of gain. It would explode. It was an important-sounding compressor. Some compressors tend to turn things down. This one kind of turns things up.”

Steel player Paul Franklin shared the area, but was separated from Mason by a large foam chunk about 8x4x1 feet. Sennheiser 421s were used on each of his cabs. Steve Nathan played all the keyboards, including the orchestra bells (overdubbed right after the basics were cut) on his synthesizer.

“A lot of people said, ‘Tell me about the theater chimes,’” Seay laughs. “And I said, ‘Well, Steve played a sample on a synthesizer. I’m not going to lie.’”

THE POWER OF VOICE

The studio had a two-channel headphone system and a gigantic 1,500-watt UREI power amp that many of the players regularly said were some of the best-sounding headphones they ever heard.

Seay says the musicians constantly remarked how inspiring it was to hear McBride in their headphones because, even though she was just providing a scratch vocal to their basic track, she was going for it on every pass. McBride used a hot-rodded Neumann U 87 converted into a tube mic on the scratch vocals. Seay says they definitely nailed it by take three, although it was probably take two. “We had great players, and the song was great,” he recalls. “It was one of those times where everything was 100 percent— the studio was 100 percent, the players were 100 percent, the artist was 100 percent. It was as good as it got.”

Classic Tracks: Steve Earle’s “This City”

Classic Tracks: Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues”

Producer Worley and engineer Schleicher oversaw the recording of McBride’s final vocals. Schleicher believes they used a Sony C800G on her voice, but he’s not absolutely certain. No one remembers the studio used, but it didn’t really matter because they brought their own gear for the vocals to keep everything consistent while Seay worked at The Money Pit. “We kind of created a vocal path—mics, preamp, compressor, EQ—that we carried with us so we could go anywhere and work,” Schleicher explains. “Our typical vocal path at the time was a GML preamp, an LT Sound CLX-2 compressor and then a GML EQ—and we were working on the Mitsubishi X-850 digital tape machine.” Schleicher says Worley’s vocal method was to warm up the artist and then have the singer do six or seven top-to-bottom performances. Then Worley would put together a comp from those takes, and Schleicher would make rough mixes and give them to the artist. Schleicher says making comps for McBride was not easy because everything out of her mouth was good.

Nonetheless, she would take Comp One home.

“And man, she would do her homework!” Scheicher exclaims. “She would come back, warm up, and sing another round of six or seven great vocals. Then Paul would take Comp One and all the new vocals and create Comp Two. For an artist like Martina, Comp Two was all you needed, but I would make a rough mix of it and she would live with it and maybe sometimes she would come back and sing it again or sometimes she would come back and we’d say, ‘Let’s just sing it again for fun. You’ve got Comp Two. It’s genius. Pressure’s off.’ Martina was so good at listening to her performances and adding new great stuff.”

MIXING MARTINA

The Money Pit had lots of outboard gear, which Seay says compensated for the minimal EQ on the Trident console. “The studio had lots of 1176 compressors, and I had four racks of gear that I was bringing,” he remembers. “We had everything we needed. I remember when I mixed the song, I used an EMT 250 Digital reverb, a Yamaha SPX 900 Digital Reverb, and we also had an EMT 140 plate at the studio. If you hear a little tape slap on her voice, it was my Roland Chorus Echo for delay. I spent about a day mixing the song and toward the end of the day, Paul and Martina dropped by and we made a few minor adjustments, and that was it.”

Seay still marvels at what an incredible record “Independence Day” is.

“It was just one of those breathtaking songs. It was so exciting,” Seay says. “It had a soaring chorus. The band was tight and tough, and it went down very quickly. It was just one of those where you felt, ‘This is a real record!’”

McBride agrees: “To me, the recording sounds like the musicians really took it seriously—not like they were playing their fourth song of the day, like it was really important. It feels to me like it has an intention that the musicians played with intention and heart—the bells, the acoustic riffs that start it out, the drums sound big. It always comes down to a lot of things that make a record work, and for that one, it was the power of the lyric, the song and the melody. When you write that lyric out, it’s poetry—all the use of metaphor and how that picture was painted, so real and raw. I think the conviction came through in my vocal, and the band played it with such energy and passion.”