In 1966, pop music was changing drastically, and so were The Moody Blues. Their 1964 Denny Laine-led Decca hit, Bessie Banks’ “Go Now,” had put them on the map worldwide, but with the departure of Laine and bassist Clint Warwick two summers later, the band seemed to be foundering.

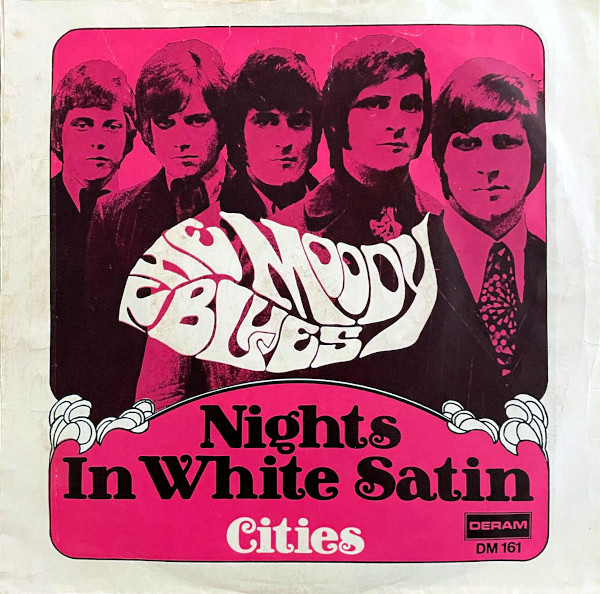

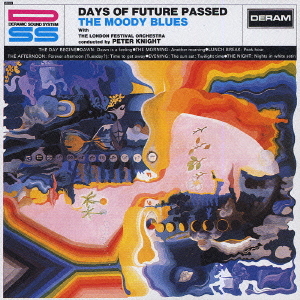

Then, in November 1966 the arrival of a new lead guitarist and singer, 20-year-old Justin Hayward, along with bassist John Lodge, the band veered in a new direction, steering away from blues-based material and entering a new realm. That turn began in earnest a year later with a new label imprint and the release of a new album, Days of Future Passed, and its hit single, “Nights in White Satin.”

Then, in November 1966 the arrival of a new lead guitarist and singer, 20-year-old Justin Hayward, along with bassist John Lodge, the band veered in a new direction, steering away from blues-based material and entering a new realm. That turn began in earnest a year later with a new label imprint and the release of a new album, Days of Future Passed, and its hit single, “Nights in White Satin.”

The band had been gigging at “workingmen’s” social clubs at the time, playing mostly R&B covers and older Moodys material, without much success. But with the arrival of the new members and a shift toward playing their own new material—encouraged by engineer Gus Dudgeon, who had tracked their newer recordings under producer Denny Cordell—the band’s profile skyrocketed.

With staff producer Tony Clarke, they recorded Hayward’s “Fly Me High” on March 30, 1967, released in May. It was recorded by Dudgeon, with staff engineer Derek Varnals tracking Hayward’s lead vocal a month later. Varnals would continue, with Clarke at the helm, to record the Moodys next seven albums at Decca Studios in West Hampstead, London.

In describing Clarke’s approach to the band’s music, Hayward notes, “He gave Days of Future Passed a much more atmospheric approach. Tony would see it in a kind of Cinemascope—he saw the whole picture somehow.” Varnals, he says, “came from a very different background than Gus; he was a classically trained sound engineer.”

Classic Tracks: Semisonic ‘Closing Time’

Varnals joined Decca in 1963 and trained under veteran engineer Arthur Lilley. “I learned to do a proper recording from the people who were there in the ’30s and ’40s, when just a couple of microphones were used,” Varnals explains. “They knew which microphones were good for which purposes and how you laid out the studio floor.”

The Decca recording center in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead, was built in 1928 by Crystalate Record Company and acquired by Decca in 1937. It included three studios: the imposing, voluminous original 1928 Crystalate Studio 1, used mainly for orchestral recording; the smaller Studio 2, located downstairs, originating from the 1928 Crystalate days; and Studio 3, built in 1961. It was in Studio 2 where Decca would audition bands (such as the famous 1962 Beatles session), and the place where the Moodys did most of their earlier work.

Around the time of the release of “Fly Me High” in May, the band appeared on the BBC’s popular Saturday Club radio show to promote the tune. They took the opportunity to introduce another new song, also penned by Hayward, “Nights in White Satin.”

Sometime in late winter, Hayward and drummer Graeme Edge returned late one night back to the apartment they shared. “We had a rehearsal room out by Mike’s [Pinder] flat in Barnes, and I knew that we were gonna rehearse up some things. So I knew I had to have something for the next day,” the songwriter recalls.

Back at his flat, Hayward grabbed his Francis 12-string acoustic guitar, one which had originally been owned by veteran skiffle man Lonnie Donnegan. “I just sat on the side of the bed with that old 12-string and just did the two verses, and that was it, really.”

The “white satin” referenced some white satin sheets that a girlfriend had given him. “I was at the end of one big love affair, at the beginning of another. So that’s where it came from. It’s what kids of 19 and 20 years old say and write down in their poetry books,” he laughs.

A New Sound

The next day at rehearsal, everyone offered up their new tunes. Hayward played them “Nights,” to minimal reaction, until Pinder, who had a new instrument, the Mellotron, stepped in. “He said, ‘Play it again,’ and I played it again, and he went, ‘[sings the song’s signature riff],’” Hayward recalls. “And that bit of fairy dust suddenly made everyone go, ‘Oh…quite interested in this now.’”

Notes Pinder: “I was inspired by the cascading strings of Mantovani and other artists, and I wanted to do a similar thing in a rock and roll context. Rock music and rich orchestral movement was what I was going for.”

Pinder had begun working at Mellotronics, the company that made the instrument, the year before, working as their “quality control” person. The band, wanting to add new sounds, decided to acquire one Pinder had helped set up at The Dunlop Social Club in Birmingham, for £25.

Among the first things Pinder addressed with the instrument was the issue of the time limit for how long a note/key could be played. The Mellotron contained individual strips of tape with recordings of instruments playing each note. Depression of a key only allowed about 7 or 8 seconds worth of play before a spring would rewind the strip. So Pinder modified the instrument to repeat groups of strips available on both the right- and left-hand keys, to allow continuous play of the same notes, as long as needed.

“We were so excited to have a Mellotron,” Pinder says. “The idea that I could be the orchestra was wonderful to me. I didn’t have to go out and find or hire a string section. I could arrange the strings, and play them, too. It opened the door to arranging our songs and adding textures that developed our sound.”

“Night” Turns Into Days

Additional singles and recordings were made through the summer, and on Sunday, October 8, they tracked “Nights in White Satin,” this time working in the larger Studio 1, which Varnals notes, “was not ideally suited to recording bands. The battle with recording a guitar band in Studio 1 was just getting the energy of the band to sound big and not diluted by the big room.”

The control room featured a 20-channel, solid-state console built by Decca and installed in early 1966. Along the back wall were two Studer 2-track C37 tape machines and a 4-track J37, as well as the studio’s original Ampex 4-track, which utilized half-inch tape (the Studer took 1-inch). A pair of reverb chambers were located on the roof, built during a 1957 expansion of the facility for stereo. Adjacent to the control room was the cutting room, in which mastering engineer Trevor Fletcher could be found from 1952 to 1980 cutting lacquers and acetates for 7-inch singles for all the Decca labels.

To account for the effects of the large space and limit the room’s inherent reverberation, Varnals pulled the band members in as close to each other as possible, screening Hayward and his 12-string off to minimize mic leakage.

A single rhythm track was recorded to one track of the 4-track Studer, Varnals adding live reverb to the Mellotron “to help blur the edges” across the uneven impact of notes. Regardless, the Mellotron still sounded thin, so Clarke decided to overdub three more onto the remaining tracks, mixing them down to the ½-inch Ampex 4-track before adding additional overdubs, including two tracks of the band’s stirring background vocals and Hayward’s emotional lead vocal (with a punch-in on that track for Ray Thomas’s flute solo). That vocal, recorded using a tube Neumann U67, was memorable for Hayward. “I was alone in the studio recording the lead vocal. It is my abiding memory of the session that day.”

The song was not mixed in time for the following morning’s regular meeting of Decca A&R executives. Clarke booked time for Varnals to mix it that Tuesday, remixed again on Thursday, with that final mix becoming the master mono mix, available as a single then and on the album’s 50th-anniversary package as a bonus track. Clarke brought an acetate of the mix to the following week’s meeting, and two days later recorded another new Moodys track, Pinder’s “Dawn Is a Feeling.”

Clarke and Varnals were asked to attend a meeting that Friday at Decca’s headquarters, at which it was decided to have the group record an entire album for the company’s new label imprint, DERAM (pronounced DEE-ram). The disc was to be recorded using a new recording methodology developed by Decca A&R man Michael Dacre-Barclay, called the Deramic Sound System.

DSS was meant to help explore and exploit the stereo picture image, Dacre-Barclay says, providing the Decca engineers a specific prescription for tracking. Varnals explains, “He told us, ‘We’ll record the rhythm section separately, in stereo, but we’ll have a bit of reverb and delay it with a tape delay. And we put the left instruments’ reverb on the right, and the right instruments’ reverb on the left.’ We called it ‘cross-delayed echo.’ And then the orchestral pieces would be added afterwards.”

Having heard Clarke’s acetate of “Nights in White Satin” earlier in the week, Dacre-Barclay and the company’s longtime LP A&R executive, Hugh Mendl, were inspired to devise a project using The Moody Blues to record using the DSS system and release on DERAM. “It was because it was spacious in sound, due to the reverb use, and was very melodic,” Dacre-Barclay says.

The original plan, as the band members recall, was to do a DSS project recording Dvorak’s “New World Symphony,” with Peter Knight, a pop music arranger and sessions fixer, conducting. “The original idea proposed to the group was to do a rock version of Dvorak,” Hayward remembers. “Peter Knight didn’t think it would work, but loved ‘Dawn Is a Feeling’ (written by Mike but sung by me) and ‘Nights.’ It was he and Hugh Mendl who proposed doing our own songs instead.”

Varnals, who attended the meetings, has a different recollection, insisting, “We were at the meeting, and Tony said, ‘Well, we’ve got “Nights” and we’ve got “Dawn” and we’re recording “Peak Hour” this afternoon, and on Sunday we’re recording “Tuesday Afternoon.” That’s half the day covered, isn’t it?’ He said, ‘We’ve got four songs, we’re gonna need at least four more. I reckon we can get away with eight.’”

The band members were encouraged to write four additional day-themed songs, which were recorded over the course of the following week, rough mixes of which were provided to Knight to work up his arrangements.

Varnals had worked with Knight on a similar recording in 1965, on a project by Edmund Hockridge. Knight conducted and listened to the rhythm section from another studio in his headphones as he led the orchestra.

Varnals spent Monday and Tuesday, October 30-31, recording another DSS album, Gypsy Romance, which featured a big orchestra setup in Studio 1. “As we were to record Peter’s pieces for the Moody Blues on Friday, November 3, I just adapted the untouched studio floor setup from that, because it was similar to what Peter needed,” the engineer explains.

While the majority of Knight’s compositions, inspired by the music heard on the rough mixes, were link pieces, “Nights in White Satin” featured the orchestra on the track itself, mainly at the end, requiring that the orchestra for that song be recorded as an overdub, not wild, as with the other orchestral pieces. So Varnals created a two-track stereo mix of The Moodys’s recording, transferred that to a new 4-track tape, and that mix was then played back to Knight in headphones as he conducted the orchestra, which Varnals then recorded as a live stereo mix onto the remaining two tracks of the tape. “It had to be in sync,” Varnals says. “That was the only way to do it.”

[Note: That unique stereo mix of the band’s work, sans orchestra, is in the vault with its own master number and would appear on later Moody Blues compilation albums.]

The single, with its mono mix done by Varnals back in October, prior to the orchestral recording, was released the following Friday, November 10. The LP itself came out the next day as a rush release, with cover art featuring a painting on the front by David Anstey. The back showed the band sitting around a table with, it turns out, Clarke, Varnals and Dacre-Barclay. “That was a staged photograph we took on the mixing weekend, on either November 4 or 5, in the small meeting room the classical producers used.” And what are they all looking at? “It was a book Michael Barclay brought in about the moon and its phases.”

While the single only reached Number 19 in England (Number 103 in the U.S.) upon initial release, five years later, in 1972, it was reissued in the States and subsequently hit Number 1, bringing a huge audience to the Moodys, which Hayward credits largely to the rise of FM radio in the U.S.

“I could never see where this record was going to be played, outside of a few enthusiasts that were into sound quality, audiophile people,” he says. “It wasn’t until we got to America in 1968, where FM was just starting, and we said, ‘Wow, that’s how you’re meant to hear this.’ It was perfect for FM radio, and that’s when it took off in America.”

Quad and Beyond

The following year, 1973, saw the album’s reissue in a new quadrophonic mix, because, by that time, Hayward states simply, “Everyone was going quad mad.”

Decca’s studio at Tollington Park was equipped for quad, and, realizing that the 4-track master—containing stereo mixes of the Moodys’s performances on two tracks and orchestra on the other—would only provide limited opportunities for front/rear sound design, Clarke suggested to Varnals that he go back to the previous element reels and copy them onto a 16-track tape, manually synching each to the first reel.

That synching was done over two days, February 21-22, 1973, by Varnals’s assistant, Dave Baker, on a pair of headphones and using varispeed to control the speed of the reel being added. The mix was created late in the second day, Varnals making the most of it by putting the orchestra up front, with a small amount of reverb in the rear channels.

By 1978, the metal parts used to press LPs in the UK had fulfilled their duty, so it was time to cut new lacquers to create more. But when the stereo LP master was pulled from Decca’s tape library, serious deterioration and damage to the Scotch 202 stock was discovered, preventing its use any longer.

“Something had oozed out of the backing and would stick to the next turn of the tape on the reel,” causing oxide to shed when the reel was rewound, Varnals recalls. “And at edits, we had the opposite problem—the gum from the splicing tape had dried out, causing the splicing tape to fall off and the edit to come apart.”

“Something had oozed out of the backing and would stick to the next turn of the tape on the reel,” causing oxide to shed when the reel was rewound, Varnals recalls. “And at edits, we had the opposite problem—the gum from the splicing tape had dried out, causing the splicing tape to fall off and the edit to come apart.”

To create new lacquers, Varnals returned to Remix Room 1 at Decca West Hampstead on August 2-4, 1978, and re-created his stereo mix, this time making use of his 16-track composite from 1973 in order to avoid having to resync the reels a second time. That stereo mix is the one that has been heard ever since—on vinyl and compact disc—until UMe’s 50th-anniversary reissue in 2017, when the original 1967 tape was restored and issued alongside its 1978 counterpart (as well as a 5.1 surround mix created by Hayward and his engineer, Alberto Parodi).

The 1967 master restoration was performed by Paschal Byrne, who worked at the studio at that time and was aware of the types of deterioration/damage that was found on the tape.

For tape portions where shedding was not too severe, he says, “it would just be a matter of possibly rebalancing within, if you had one side that was slightly lower in level than the other. It was just a matter of being aware of the noise floors, if you could get away with increasing the level or certain frequencies across those points.”

But for those sections where the damage was too severe, Byrne carefully cut in a copy of those few beats from the 1978 stereo remix. “But even that had its own slight issues. A remix is never exactly the same as the original it’s re-creating. It’s just a matter of finding the right splice point. Our goal was to keep the stereo experience as true as we could to the original. So we tried to keep the splicing from the newer stereo mix to a minimum.”

For Hayward and Parodi’s 5.1 surround mix, only the 4-track quad master was available, Hayward recalls. “My engineer, Alberto, said, ‘They’ve got four tracks—that’s it!’ So our focus was simply to carefully add a bit of ambiance to it. But everything was there.”

What’s heard in both the 1967 mix and the later remix are the same: quality. “I give Derek all the credit for the sound of that album,” Hayward states. “The standards that he set, which took us right through the next six albums, is something that, at the time, I just took for granted. That was the way it was done. I’m just very thankful for the ethic and standards Decca had. The attention to detail in that place was fantastic, and you can hear it.”