In Season 2 of the hit HBO series Treme (2010-2013), characters Harley Watt (played by Steve Earle) and Annie Talarico (Lucia Micarelli) catch John Hiatt performing his beautiful ballad “Feels Like Rain” in a club. Annie feels the song was written about Hurricane Katrina, until Harley points out that the song predates Katrina by 17 years. This prompts one of several conversations the two characters have about songwriting, what makes a song great, and what makes a song universal.

In another scene, Annie keeps Harley company while he works on lyrics for a new song. He’s feeling around for what comes after…

“This city won’t ever die / Just as long as her heart beats strong / Like a second line steppin’ high / Raisin’ hell as we roll along / Gently to the Vieux Carre Lower Nine / Central City, Uptown…”

Then Annie almost absentmindedly sings, “Singin’ jacamo fee-nah-nay,” and they both add, “This City won’t ever drown.”

It’s the audience’s first chance to hear “This City,” Earle’s poignant, original composition for the Treme soundtrack. The song is arguably both pointed and universal. It’s definitely great, and we can safely assume Earle didn’t actually need help writing it.

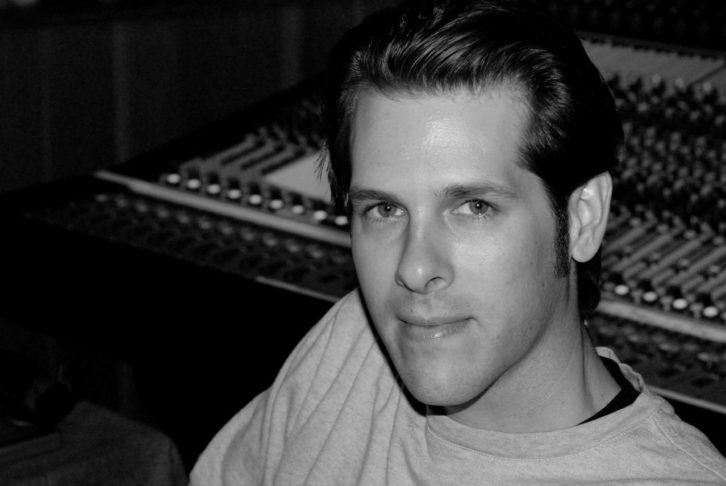

Produced by T Bone Burnett and engineered by Jason Wormer, “This City” was recorded in a bit of a whirlwind in Piety Street Studios (New Orleans). The track also appears on Steve Earle’s album I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive, but it was recorded and mixed separately for the series months before the other album tracks.

Asked to dig into his memory bank about the session, Wormer starts with a childhood trip that was top-of-mind when he arrived in New Orleans for the first time since Katrina: “I first went to New Orleans in 1993 on a high school trip,” he says. “I was 18, playing guitar in the jazz band. We visited Bourbon Street and Preservation Hall—all kinds of musical destinations. It was amazing.

“We went to see some old building—I think it may have been an old plantation—and I looked off across the field and there’s this big wide hill,” he continues. “I remember asking the tour guide, ‘What’s that hill?’ He says, ‘That’s the Mississippi River. You should walk over and check it out.’ So I walk across the field and up this 30-foot berm, and there’s the Mississippi River. The river is 20 to 30 feet above the ground. Literally, I remember thinking, this is not a good idea.

“So flash-forward to 2011 and this was on my mind when T Bone and I were heading to New Orleans to record this session. At the time, T Bone didn’t really tell me what it was for. He just asked, ‘Hey, do you want to go to New Orleans and record Steve Earle?’”

PIETY STREET STUDIO

Wormer arrived in New Orleans on a Saturday, a day before the session, and drove to Piety Street to see the studio. Installed in a former post office building, it had been one of the first facilities to reopen for business after Katrina back in 2006. Wormer met with the studio techs who would be helping him out the next day.

“All I knew at that time was we were supposed to be recording Steve Earle and some horns. No one had told me what kind of horns, or that a bassist was showing up, let alone that Allen Toussaint was coming in!” Wormer says. “I laid things out for the tech staff: This is where I want to set up the horns, we’ll put Steve in the big booth, assuming he would play with the horns. I gave them specs for Pro Tools and the [Studer A827] tape machine and headed to the hotel. Our downbeat was for 11 a.m. the next day.”

Wormer began to sweat when he returned to the studio at 9 the next morning. Nothing was set up. The crew were there, but they were still eating breakfast in the lounge. “I asked, ‘How’d the tape setup go?’” Wormer recalls. “They hadn’t done it yet. The two techs started aligning the tape machine, and then I saw T Bone walking in. We had no microphones set up, no chairs, no headphones, music stands, nothing.

“I just dove into the mic locker and started pulling things out and setting things up. I’m in a frenzy because I know close behind T Bone will be Steve. I run into the control room and set my mic levels without ever hearing anything; meanwhile, the techs are still behind the tape machine trying to get it aligned. Around 10 o’clock, an hour before downbeat, Steve comes walking in strumming a new guitar he just bought. And the tape machine still isn’t up and running. Steve announces, ‘I’m just going to go in there and mess around a little bit, and I’m like, ‘Cool.’”

Which is how Wormer was trying to play things as he followed Steve Earle into the booth. For Earle’s vocal, he put up a Neumann U47 running through a Neve mic pre into an LA2A. An RCA 77, paired with another Neve pre and an EL8 Distressor, were chosen for acoustic guitar.

CAPTURING MAGIC ON THE FLY

“I’m standing next to Steve in the booth adjusting mics and he plays like half of a verse,” Wormer says. “I look through the window into the control room and see an assistant giving me the thumbs up; the tape machine is now aligned and ready, so I start mouthing and motioning to him, ‘Hit Record! Record now!’ He hits Record on the tape machine, I exit the booth, sliding the door closed behind me, and Steve ends up playing the full take that we used, without me ever getting a soundcheck.

“By the time I got to the control room, he was already halfway to the first verse and I was just praying that the levels were fine,” he continues. “After he finished the take, T Bone asked, ‘Did you get it?’ I said, ‘I think so.’ He told Steve, ‘Come in, let’s listen back.’ We listened to it, and they both said, ‘That’s it!’ We had the main track 40 minutes before downbeat.”

Horn players started showing up at Piety Street around 10:30, including the elegant Toussaint, who had arranged the horn section. “Allen did not disappoint,” Wormer says. “He showed up in a white Cadillac convertible wearing a white suit. He got out of this car, and we went out to meet him. He took off his jacket, folded it up, then put it in the trunk and pulled out his charts.”

Wormer had set up stations with spot mics for the players to play in a line, in the center of the studio and facing the control room. Toussaint stood in front of the musicians with his back to Wormer. There was a flugelhorn (played by Tracey Griffin) through an RCA 44; trombone (Sammie Williams) and euphonium (A. Michael Brown), each of which went into one of Wormer’s AEA R84 ribbon mics; and a tuba (Jonathan Gross) that was miked with a Coles 4038. Each of the horn mics went through one of the Neve mic pres, as did the Blue Baby Bottle microphones that Wormer used as right- and left-side room mics.

“We did the flugelhorn, trombone and euphonium as a group, and then the tuba and bass were overdubbed afterwards and doubled,” Wormer says, referring to his original Pro Tools session. During the horn session, he operated Pro Tools while the studio crew ran the tape machine. “The Pro Tools rig was placed to the right of the console,” he explains. “If you were looking at the Pro Tools monitor, you couldn’t really see into the studio; you were kind of turned the other way. So, this thing started happening with Allen and I where he would motion with his hand to tell me to stop and go back. But it seemed every time I glanced at Pro Tools, he would signal a stop and I would miss it. I was trying hard to get in sync with him, while simultaneously making sure that I was duplicating playlists, setting up 2-bar lead-ins, and punching in where I needed to. He definitely got frustrated more than a few times, and let me know it.

“At one point, I realized that T Bone and Steve were dying laughing on the back couch. Looking back now at the Pro Tools session for that first horn track we did, there were about 30 punches. I remember jokingly asking T Bone to help me out, but I guess it was good comedy for him and Steve.”

Roland Guerin’s acoustic bass was also captured as part of the horn session. Wormer says Guerin mainly played long-held notes with a bow, and the engineer put up either a U47 or 47 FET for that.

Classic Tracks: “Summertime Blues”

The Who’s “Baba O’Riley” – Classic Tracks

Classic Tracks: “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing”

MIXING AT THE VILLAGE

The last piece of the puzzle—Jay Bellerose’s drum part—was recorded back in L.A. in Studio B at The Village. In keeping with the New Orleans feel of the song, the drummer brought in a bass drum that he put on a stand. “I think the idea was for the music to sound like a second line, where you’d see a guy playing a drum on his chest,” Wormer says. “Jay came in and played, and then we mixed the song there in Studio B, on the Neve 88R.”

As the Treme series progressed, Steve Earle’s fictional alter-ego, Harley, was killed by an armed robber, but “This City” is resurrected by his friend: Harley leaves behind a wealth of finished and unfinished songs that Annie polishes and records as posthumous collaborations.

Meanwhile, in real life, “This City” was released both on I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive (New West, 2011), the remainder of which was engineered by Mike Piersante, and on the first Treme soundtrack album (Interscope, 2010). The song was then nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Song Written for Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media; and for an Emmy in the Outstanding Original Music and Lyrics category.

“I’ve always thought of that session as being a very funny day for me, career-wise,” says Wormer, whose credits also include recording and/or mixing for Elton John, Lana Del Rey, Rhiannon Giddens and many others. “But when I listen to it now, I realize the guitar and vocals really sound good. It looks like I got lucky that day.”