You know it the moment it starts: that unmistakable bassline, Lou Reed’s“Walk on the Wild Side” recast as the slinky pulse of a head-bobbing hip hop classic. Then, that greasy, jazzy drums sample lays down the groove. Things settle in for a few bars, and Q-Tip asks, in that buttery drawl, “Can I Kick It?” Yes, you can.

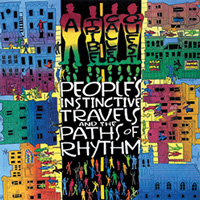

Everyone’s favorite hip hop anthem was the third single released off A Tribe Called Quest’s debut album, People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, released on Jive in 1990. The record, with its intricate collages of samples that drew from a wide palette of ’70s jazz and rock, its youthful, exuberant energy, and its positive, Afrocentric message, helped lay the foundation for a new school of hip hop. It was innovative, soulful—a party record with a conscience.

The album was recorded in 1989 as hip hop was entering into its first Golden Age. Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Jarobi White, Malik “Phife Dawg” Taylor, and Kamaal “Q-Tip” Fareed had grown up in Queens and Brooklyn, listening to their parents’ jazz records and the sounds of neighborhood DJs from their fire escapes. Their idols were LL Cool J and Run DMC.

As the hip hop sounds of the streets gravitated toward radio, the teenagers went crate-digging after school at record stores in the Village, mining the dark, obscure corners of rock and jazz to build beats. They started writing rhymes that captured the essence of growing up black teenage boys in ’80s New York City. They made some demos, which caught the attention of Jive Records.

People’s Instinctive Travelswas recorded at Calliope Studios (and to some extent, Battery Studios )in New York, by a team of engineers that included Anthony Saunders, Shane Faber and Tim Latham. But it was producer/engineer Bob Power who ultimately forged an enduring creative partnership with Tribe, one that would continue though the completion of People’s Instinctive Travels and subsequent albums.

Power, currently a professor at NYU’s Clive Davis Institute, has long been recognized as a Grammy-winning producer/mixer who helped shape some of the most iconical bums in hip hop and R&B. But in 1989, he was transitioning from being an in-demand jingle writer, guitarist and arranger to full-time engineering, and he was working at Calliope.

“This was a really big time of learning for me as an engineer, and it was fascinating,” Power says of his early days at Calliope, a low-budget studio in a loft on a gritty stretch of West 38th, near Eighth Avenue. “Even through I had scored TV for years and produced a lot of stuff, I was really happy at that point to be concentrating on engineering. Because we were one of cheapest studios in town, that’s where musicians doing new, non-mainstream things would come.”

The studio’s accessibility and vibe attracted the Native Tongues collective, a group of local artists—including the Jungle Brothers, De La Soul, Queen Latifah and BlackSheep—who were pioneering the use of samples, and jazz- and rock-influenced beats in hip hop. The acts gravitated toward Power’s creative energy and willingness to experiment in the studio.“They were good people, trying to do something a different way, and I found it fascinating,” Power says.

Members of the collective could be found recording at Calliope while Tribe worked on People’s Instinctive Travels. “It was another worldly place,” Q-Tip told Wax Poetics in 2015. “I was 18 years old; I was a kid in a candy store. Those tools in the studio became extensions of my imagination and thoughts… The rest of the Native Tongues were there with us, and we made each other better. We were a family.”

In the studio, Tribe were aiming to make new music out of the sounds they loved. “We were making do with what we had,” Q-Tip says in a scene in Michael Rapaport’s documentary Beats, Rhymes & Life: The Travels of A Tribe Called Quest.“So we take these turntables and they become our instruments… all we did was take all of those things that we were influenced by, and mix it together.”

Although “CanI Kick It?” is a complex construction of samples, instrumentation, scratches and call-and-response rhymes from Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, three samples essentially form the spine of the song: The rhythm is built from a drum break and Hammond riff from Dr. Lonnie Smith’s “Spinning Wheel,” from the 1970 album Drives; there’s a reverb-y guitar slide from Dr. Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band’s buoyant 1976 calypso-disco track “Sun Shower”; and there’s Herbie Flowers’ “Walk on the Wild Side” bass line—originally recorded by Ken Scott and doubled on a Fender electric bass and an acoustic double bass—which forms the melodic glue.

Q-Tip and Muhammad reworked records,and Muhammad played live instruments and performed scratches. Meanwhile, Power was experimenting with early sampling technology, trying to stretch the limits.

“You have to remember how incredibly primitive MIDI and sampling technology were at that point,” Power says, recalling the days of working on early Apple machines with 128k of memory.“Unless you lived through it, you have no idea. Just to run a sequencer, you had to pop in a floppy, boot up the operating system, take that floppy out, pop in another floppy with the software for sequencing and leave that in there for the whole time you were sequencing.I call it the Wild West—flip a bunch of DIP switches and see what happens. It’s so easy now to open up the computer and just have everything spring to life.”

Elements were locked to SMPTE timecode with a 12-bit E-mu SP12 sampling drum machine. Track slipping was still not available in software (Power believes he was still working with Notator/Creator on an Atari 1040 at that point), so in order to move sounds into the right places against the beat, they devised a genius workaround. “We would run everything through a 100-millisecond delay, so everything that happened referenced to that timecode,” Power explains.“The zero point, the center of the beat, was 100 milliseconds behind where it was supposed to be. And then if we wanted to move something forward or back in the feel of the song, we would change the delay that the timecode was going through to say, 50 milliseconds if we wanted to be ahead of the beat, or 120 milliseconds if we wanted to be more behind the beat.

“The guys would sequence stuff on the SP12, or Ibelieve we were using Akai S900s, and at that point, the sampling time was like three-quarters of a second, or a second-and-a-half; it was ridiculous, ”he continues. “And because of the short sampling time available, if there was a loop that was longer than, say, that second-and-a-half, we had to lay it down in pieces to different tracks on 2-inch. Say it was a one-bar loop: You’d lay down the kick, the snare, you’d lay down into beat three, then you’d lay down beat three through beat four, and then work like hell to make sure they lined up and sounded good together.”

Power spent a lot of time cleaning up samples, which he says he would never do today because he now understands, “The schmutz on the track, the stuff that’s not supposed to be there, is really what gives the composite track its flavor. ”Back then, he would hone in on the most salient elements of every sample through EQ and filtering.

“If it was a Rhodes part, I might filter it such that mostly what was left was midrange, which was where the Rhodes lives, so we didn’t hear a lot of bass or kick drum, hi-hat, stuff like that,” he says. If the sample had a lot of surface noise, he’d sometimes run bits through a piece of hi-fi gear called a Burwen Noise Eliminator.

For the MCs, Power tended to use C414s on vocals, and everything was laid to Calliope’s 3M M79 2-inch. “One MC would go in and lay down the rhymes, and the other guy would go in and lay down the rhymes, ”he recalls. “They didn’t always walk in to the studio having that together. A lot of the time it was like, ‘Okay, let me just cycle the tape and leave the room for an hour while somebody writes their rhyme.’”

It’s important to remember that before Tribe and their Native Tongues contemporaries came along, hip hop music was mostly built around simple, single-bar loops of standard R&B samples, laid over 808 beats. With People’s Instinctive Travels, it was like they were creating a record and a new art format the same time.

“This is a great example of technology informing art,” says Power. “It sounds simple, and it sounds obvious, but the increase in sampling time that became available allowed people to make more and more elaborate constructions. So in a sense they weren’t just deconstructing something, they were really reconstructing something in away that could not and would not have been played by ‘real’ musicians or live musicians because all of this stuff came from different songs. And it came to this recombinant kind of groove that you never could have done in any other way.

“Something to think about interms of the brilliance of Ali Shaheed and Tip was that many times the samplers and drum machines that they had didn’t have enough memory to hold all of the samples to construct a song,” he adds. “So they would actually hear things in their head, and put it together in their head before hand, which is amazing.”

People’s Instinctive Travels met with critical success but was slow to attract mainstream audiences; it took six years to reach Gold. And due to licensing issues, Tribe has never received royalties from “Can I Kick It?” Lou Reed held onto the publishing rights, as Phife Dawg explained to Rolling Stone on the 25th anniversary of the album. “I’m grateful that [the song] kicked in the door, but to be honest, that was the label’s fault,” he said.“ They didn’t clear the sample. And rightfully so—it’s his art, it’s his work. He could have easily said no. There could have easily been no ‘Can I Kick It? ’So you take the good with the bad. And the good is, we didn’t get sued. We just didn’t get nothing from it.”

A Tribe Called Quest’s studio partnership with Power continued for three more albums: the landmark The Low End Theory, which catapulted the band to legendary status; Midnight Maurauders; and Beats, Rhymes & Life. “He was the fifth member of A Tribe Called Quest,” Phife Dawg told Wax Poetics in 2015, in one of his final interviews. “He knew what we wanted before we even told him… it was the easiest part of working on this album.”

Nearly three decades later, People’s Instinctive Travels still sounds fresh and relevant—a testament to Tribe’s musicianship and honesty in their rhymes. “I remastered the record for the 25th anniversary release last year, and when I listened to the songs over and over again,I realized that I still really love all this stuff; it has a great life to it,” says Power. “Anybody who makes records knows that that’s kind of an ‘X factor.’ The magic doesn’t always happen; we have enough technique to make it pretty good even if the magic doesn’t happen, but there was certainly magic in those tracks.“