It had been 15 years since Don Henley released a solo album, but when he finally did, he decided to take listeners for a ride in the country. Nashville, to be specific, where the majority of Cass County (Capitol) was recorded and mixed, using mostly local session players and engineered by one of the town’s top engineers, Jeff Balding, over a period of nearly five years.

Co-producing with Henley was longtime collaborator and former Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers drummer, Stan Lynch. The two have been writing and producing on Henley’s records since producer Danny Kortchmar introduced the two during the production of 1989’s The End of Innocence; Lynch also worked on The Eagles’ Hell Freezes Over reunion project in 1994.

Cass County got its start in late 2009, following the initial leg of The Eagles’ Long Road Out of Eden Tour, when Henley called Lynch from his home in Dallas about making a new record—in Nashville. “I’d enjoyed making demos and records there, but I’d never done anything at this level,” Lynch notes. “I suggested us recording there to Don, and he said, ‘Hey, let’s give it a shot!’”

To get his feet wet, Henley decided to begin by recording demos of some covers, themselves country favorites—including Billy Sherrill’s “Too Far Gone,” the Louvin Brothers’ “When I Stop Dreaming” and Tift Merritt’s “Bramble Rose,” which would eventually serve as the album opener.

The demos were tracked at Luminous Sound in Dallas by engineer Chris Bell, with Eagles touring guitarist Steuart Smith (another regular co-writer with Henley and Lynch) and pedal steel player Milo Deering contributing. Both would prove major players in the sound of Cass County.

After another leg of Eagles touring in the summer of 2010, Henley and Lynch returned to Dallas to continue the demoing—and writing—process, this time at Henley’s home facility, Red Oak Studio. Engineering was handled initially by Hank Linderman, who, with Richard Davis, typically mans Henley’s home studio in Malibu (which Lynch describes a veritable “history of recording,” due to the presence of classic analog gear Henley keeps). Some demos and initial tracking for some titles were also done at the Malibu studio, including “Train in the Distance,” “Waiting Tables,” and bonus track cover, “It Don’t Matter to the Sun,” which features Stevie Nicks dueting with Henley. Most later rounds of demo recording at Red Oak would be tracked by Gordon Hammond, who would assist Balding in Nashville.

Red Oak’s engineering setup is not unlike a basic mobile arrangement, with a Pro Tools HD rig, an Avid Icon console (which went unused here), a pair of Avalon Design Vt-737sp channel strips, API 512 and 550 preamps, UA 1176s and a Neve 33609 compressor. Henley sang into a Neumann U 47, with other recording covered by a Shure SM7, with Hammond supplementing those with his own Miktek C5s for acoustic guitars and some Cascade Fathead ribbon mics. “We used four mics at a time, and if we did drums, it was two mics—we were just trying to get a feel and a vibe,” Lynch says.

Working typically 10 days at a time together, the engineer explains, “Stan and I would get up and go to work, building up some tracks, and then take them to Don, and Don would then spend time developing his lyrics and come back and sing, doing quite a lot of writing at the microphone. There would be a lot of back and forth—Don would tweak his lyrics and come back and sing alternates, we might change the key—just working it out. He’d change words, write new parts, all the way through the process, always trying to make it better and better.”

Percussion often consisted of a work loop made of Lynch, perhaps shaking a box of rice from Henley’s kitchen, perhaps filled out later by a musician. “The demos were just the beginning of those songs, just trying to get some structure, tempo and key stuff figured out before bringing it in front of a band,” Hammond explains.

By January 2011, it was time to take the songs to formal tracking in the studio, so Lynch connected with Balding, whom he’d known from occasional work he’d done in Nashville, and with whom he’d always wanted to make a record. “Besides his obvious sonic skills, he has the right kind of personal qualities,” says Lynch. “He’s very controlled in how he presents his case, always in a rational way that makes sense, not talking out of any ego. And with a top-tier artist like Don Henley, having the right personalities and chemistry is critical.”

The first sessions took place in Studio A at Sound Emporium (where Hammond, at that point, served as a staff engineer, moving to assist Balding for this project). The batch of six songs included mostly covers, such as the catchy “The Brand New Tennessee Waltz” (found on the album’s Deluxe edition), “When I Stop Dreaming” and “She Sang Hymns Out of Tune,” as well as new tracks like “Waiting Tables” (originally an Eagles candidate track).

The first step in the process always involved Henley, Lynch and Balding evaluating the demos to determine if any of those versions could either form the basis of the final track or offer a part to retain, or if the track should be cut anew, which was frequently the case. Notes Balding, “They’d come in with the demo and say, ‘You know, we think we can raise the bar on this by recutting it.’ Or Don might say, ‘There’s something going on here that I’m not hearing, that I’m wanting out of it,’ whether it was a drum part or a bass part.”

Sometimes it was Balding who would help his colleagues see where an improvement could be made. “I’d say, ‘Jeff, open the files on this song and tell me what you think,’ and you could read him like a book,” Lynch says. He’d say with a smile, ‘Well, have you met Jimmie Lee Sloas? He’s a really great bass player.’ Oh, I get it,” he laughs.

Lynch and Henley drew upon a core group of musical talent, both for tracking and overdubbing, including (but not limited to) Steuart Smith on guitar, Greg Morrow on drums, bassist Glenn Worf, and Tony Harrell on piano. Milo Deering’s pedal steel was recorded in Dallas at Red Oak, while the team drew on Nashville-based Russ Pahl and Dan Dugmore when needed locally.

Though pedal steel is thought of as a central instrument to country music, the producers’ and Balding’s approach for it, as well as all instrumentation, was a simple mixture of basic, well-performed music supporting Henley’s vocals. “One of our mandates on this record was, ‘How little can we get away with?” Lynch says. “I would listen to Patsy Cline records, and there’s nothing on there that doesn’t need to be. So it was, ‘When in doubt, leave it out.’”

Though he does not perform any instruments on the record, Henley would typically sing his vocal live with the backing musicians, working with them on the arrangement as recording would proceed. “Don arranges on the fly,” Lynch says. “He would be at the microphone, and you’d hear him say, ‘Hey, man, I like what I’m hearing. Let’s go around a couple more times on that.”

The musicians drew strongly from Henley’s vocals, both in tone and in his skillful phrasing, to the point of insisting he could be heard well while tracking, Lynch recalls. “We were cutting ‘Too Much Pride,’ and Glenn Worf actually said, ‘Here’s something I don’t always say—Turn the lead vocal up in my headphones.’ And you heard the whole band go, ‘Yeah.’” Adds Balding, “Guys at that level are listening to the lyrics, and they’re playing what they play to those lyrics. They want that vocal in their ear.”

Balding typically recorded Henley’s vocals with either a Neumann U 47 or M 269, depending on the song. For drums, he would use anywhere from three to a dozen microphones, with both high and low overheads and extra room mics, both close and far.

There are plenty of guest vocalists—some trading verses with Henley, such as Merle Haggard on “The Cost of Living” or Dolly Parton on “When I Stop Dreaming”—most of whom Henley planned on at the writing or demoing stage. “He wrote that second verse with Merle in mind,” Lynch recalls. While Lynch provided a click track for Parton as a lead in for the a capella opening to “Dreaming,” she requested he remove it. “I asked, ‘Well, how are you going to know when to come in?’ and she answered, ‘Turn up Don’s vocal; I can hear him breathe. When he inhales, I know he’s gonna sing.’ It was magic.”

A plethora of other country stars also appear—including Trisha Yearwood, Vince Gill, members of The Dixie Chicks, Alison Krauss and others—but singing only harmony vocals or backgrounds. “It’s fairly common in Nashville to see people record on each other’s records,” Hammond says. “It’s a communal small town; everybody knows everybody.” Henley, himself unequalled as a harmony singer, would guide his guests some, but would also allow them to do what they do best. “My theory,” says Lynch, “is never discourage a generous impulse. We can always focus it, if we feel like it’s a getting a little wide.”

The cycle of demoing and tracking would continue over the following two years at a variety of studios around Nashville, including House of Blues, Blackbird Studios, and Trisha Yearwood’s and Garth Brooks’ Allentown (the former Jack’s Tracks, built by Jack Clement, located on Music Row), the latter two serving as “home bases” to most of the project.

“Allentown’s very private,” says Lynch. “So Don would sequester himself on the second floor and go into a lyric lockdown. I’d go downstairs and use it as a laboratory to do some demoing,” working with Hammond (assisted by Matt Allen), for both demo and track recording.

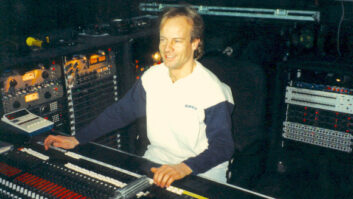

By July 2012, there were 14 tracks ready, which Balding would begin mixing at his personal studio, Opolona Mix Room, a hybrid space with an API 32-channel analog desk, a host of outboard gear and large selection of plug-ins, including favorites from Universal Audio.

The process—which carried on for more than a year—would involve Balding creating his mixes, and then Henley living with them for several weeks, then returning comments, typically involving requests for level adjustments. “Henley hears the smallest of details,” says Balding. “He would have tweaks that would involve adjusting something sometimes by as little as one-tenth of a dB.”

With the cycle of refining and whittling continuing over time at various studios, Balding felt it necessary to work close to where recording was taking place, requiring him to be able to recall mixes at one studio in Blackbird to allow him to include new instrumentation/vocals recorded elsewhere at the studio. To do this, he created mixes that could be easily recalled from his original Opolona analog-based mixes.

“Because I automate my levels in Pro Tools, I could use tones to document fader levels on my console, which could then be used to recall the correct fader levels for the mix at Blackbird,” he describes. “Between the recall documentation, the plug-ins I used on the mixes and a few key pieces of outboard gear that I took with me to Blackbird, the mixes could be recalled with great accuracy.”

When the mixes were finished and ready for mastering, Balding would print individual instrument stems, along with the stereo mix versions, and then use the stems to make any last-minute adjustments needed, even during mastering. “To ensure the stems truly represented the stereo master mix, I fed an uncompressed stereo mix into the keyed input on the stereo bus compressor, so it reacted the same on each stem mix as it did on the stereo master mix. This allowed the sum of the stems to exactly match the stereo master mix.”

The album was mastered by Bob Ludwig at Gateway Mastering in Maine. “Bob really latched onto the organics and the structure of the whole record,” Balding notes. “When he heard it, he got it, and then just raised the bar again on it.”

For Lynch and Balding, working with a legacy artist like Henley meant an opportunity to spread out and enjoy his making available whatever resources were needed to make the record he envisioned, for a project Henley had quietly always wanted to make happen.

“Don knows precisely what he is looking for,” Balding says. “I actually feed off that, because we’re all reaching for the same goal. You get inside the artist’s head and the producer’s head as much as you can, and then add what you feel on top of that.”

Adds Lynch, “And the way Don went after it, allowing as much time and talent as was needed to do that is a critical process nobody gets to experience anymore these days. It was an incredible pleasure to be part of that process.”