photo: Mr. Bonzai

Friday nights here in L.A., producer Jon Brion hosts a (humorous) musical variety show at Cafe Largo. Improvisation, new tunes, oldies done with a devilish twist, surprise guests, retro instruments, colorful rock and tasteful roll. You might hear Brion playing “Sympathy for the Devil” on an accordion. At his request for song ideas, someone shouts out, “This guitar string is wrapped around my heart,” and Brion weaves a believable song around it.

Born in the rough woodlands of New Jersey, Brion has been living in L.A. for the past 15 years, gathering accolades for his ability as a multi-instrumentalist with an eclectic collection of string and keyboard instruments, odd electronic gear and choice vintage mics. As a producer, the albums include work with Rufus Wainwright, Aimee Mann and Fiona Apple. In the film world, he has created memorable soundtracks for Magnolia, Punch-Drunk Love, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and I Heart Huckabees.

The surprising news is that Brion has produced his first hip hop album: Kanye West’s Number One smash, Late Registration. Brion collaborated with West on creating the new songs, as well as playing guitar, keyboards and providing string arrangements. Guest vocalists include Cam’ron, Brandy, The Game, Jamie Foxx, Jay-Z and Maroon 5’s Adam Levine. Brion’s longtime engineer, Tom Biller, gave me a tour of the funky Grand Master recording studios, where tons of strange instruments were being hauled out of storage to get the job done. Then I sat down and talked with Brion.

How did all this materialize with Kanye West?

I was standing in a music store and got a call. “Hey, man, it’s Kanye. Thought we should get together.” His last album wasn’t just boasting, as is common with rappers. He stayed on topic; he is focused on the songs. That’s why I like working with artists like Fiona Apple and Aimee Mann.

He came in with the basic samples and drum beats, and sometimes a verse of the raps. We’re doing all sorts of things with real instruments. Turns out he liked the soundtrack to Eternal Sunshine and the second Fiona record. He liked the fact that I got sounds that were different from the norm.

I discovered that he is a great drum programmer and great at manipulating samples. I introduced him to the Celeste and it blew his mind, and then to the Chamberlin. I said, “Here is the original sampler, invented in 1946, and there’s a tape player under every key, with recordings on this one of the Lawrence Welk Orchestra recorded in the late ’50s.” I put my hand on the keys and you could see fire shooting out of his eyes, he was so excited. So here we are with the instrument collection, and we are following my obsession of making new sounds appear in a very organic way.

You finally have all your instruments out of storage?

Yes, here at Grand Master recording studios, famous for sessions with Ringo Starr, Billy Preston, Harry Nilsson and Beatles-related ’70s-era stuff. I came in to do a little instrumental project, and Kanye came by the very next day. He brought along some Pro Tools files, but I didn’t really know what he wanted to do. I introduced him to The Pile, which is what we call this collection of instruments and old electronic gear. Within half-an-hour, he was playing me rough mixes and I was suggesting things we could add. A microphone came up, and two days later, we had worked on three or four songs. He looked up at me and said, “Are you producing?” I looked at Tom and we both laughed, and I said, “Okay.”

Did you go back and study his previous work?

I knew the last record, and I am incredibly impressed by his instincts. He will do his rap, and then sing a chorus, sing an octave above it, then come in and listen. He tells me, “I need somebody with a reedy voice to do the top part and somebody with a huskier voice for the bottom part. He starts mentioning people he has in mind. I said, “You just wrote the chorus and you figured out mentally how it should be presented.” He thinks in frequency ranges.

I can recognize when someone sees music architecturally, which is how I work. I see it as a spatial thing: left to right, front to back, up and down. It’s animated and it’s moving in real time. Kanye has that. He said, “I see things in my head and they are complete and then I have to put it together in the recording.” He tries things out until it fits, until it sits where it is supposed to sit and everything has the correct emotional function. He has real instincts like any great record-maker.

You’ve never made a hip hop record.

No, and I’ve wanted to make one for 10 years. The influence of that music is all over everything I do. The first record I produced, for Aimee Mann, has tons of the influence of listening to hip hop and rap records. Nobody ever gets it because they see the Beatlesesque pop things and recognize that. They hear some of the wackier stuff and know I have a love of early jazz and stride piano.

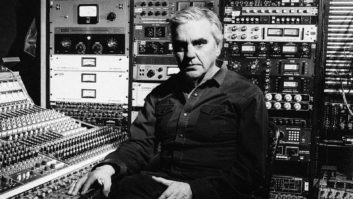

Jon Brion’s engineer, Tom Biller, slaving away at the board

photo: Mr. Bonzai

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, I was attracted to hip hop because, unintentionally, they were playing with different eras of fidelity at the same time: Here’s this bit from the ’60s and something current right next to each other. Rock records were either all modern or all retro. I hated the way reverb and samples were used on records in the ’80s and even today. Generally, I don’t like digital reverb. I was reacting against that and how records had “spatialness” based on how wet it was. The only wetness they knew was bright, hissy and awful. Multi-relays on guitars. And it obscured what was originally there.

I started doing things as a result of hip hop influences, those accidental combinations of fidelity. What if we had something that sounded like it came off a Nelson Riddle record and just in the left speaker? And over here we have something from this era. I wanted to make sure that people realized it wasn’t strictly retro. That Aimee Mann record [I’m With Stupid in 1995] — not a mid-’60s melodic pop record — has lots of stuff that is decidedly modern with some left-field material.

You’re a troublemaker, aren’t you?

Yeah. Going back to the second Fiona Apple record, it was very much an experimentation of the influence of both electronic music and loop music, but not looping things — using synthesizers for the most part. Everything is played on that record. Those aren’t drum loops; Matt Chamberlain is playing those drum parts, except for one Optagon part that was looped. If there was a repetitive keyboard part, I played a three-to five-minute performance. It still has the hypnotic effect, but it has the human element, too — like a weird combination of electronic music, Reich and Eno influenced, modern and feeling classic because you have the human element.

I thought this kind of sound would be great on hip hop records because it feels as solid and tight as a machine, but is human and funky. Kanye is the first person to make the connection on a purely sonic level. He noticed some sonic signposts. And his decisions are intuitive and not random. Once he was here, it freaked him out that I was playing parts-oriented stuff for the whole take rather than playing chords or noodling.

He came up with a great part the other day when I set up a weird old early sampling keyboard, the 360 digital keyboard — the first commercially available sort of sample player. We are bringing out a lot of early ’80s technology because he relates to the synths and drum machines. What’s interesting is that our tastes are similar, but not in specifically the records we listen to but what we listen for. Quality of experience. How it connects with the body. When there is a decisive change in the record to keep your interest up.

All those little things are the intrinsic heart and soul of record-making. It’s why Rick Rubin and Dr. Dre are the producers of their generation. I don’t think anyone else is even close. It is no accident that they have had careers nearly two decades long, consistently hitting the mark. They have a sense of what a record is supposed to be about and they bring that to the studio.

With hip hop, the notion is that you always have to have the latest “thing.” But what’s funny to me is that the sounds that everyone likes are coming off these old records. The sounds went through multiple tape generations before going to the mix and then to vinyl, and then the records were kicked around for 20 years before they were sampled. That’s a lot of generations to have the EQ softened, for it to get grainy. But that’s what works.

Me with my piles of instruments, with knives and forks stabbed into them to keep them working — these crazy half-working instruments — actually help to make the sounds that hit the spinal chord in the way that Kanye wants. And Kanye is loving it. I have an excited artist. One of the reasons I collect old equipment is because of the way different artists react as they come into this unfamiliar environment. We get new sounds that are very, very interesting. They want to experiment, they start playing around and that’s when I like to start recording.