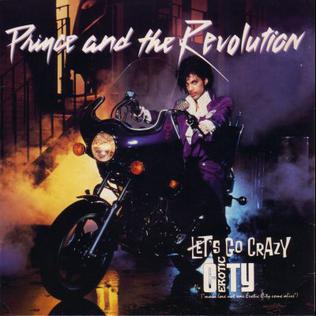

Recording “Let’s Go Crazy” at The Warehouse in St. Louis Park, Minn., in October 1983 for Prince and the Revolution was baptism by fire for engineer Susan Rogers. While the August 3, 1983, live show at First Avenue provided the bed for the three tracks they re-worked in the studio—“I Would Die 4 U,” ‘”Baby I’m a Star” and “Purple Rain”—Prince decided to completely re-cut “Let’s Go Crazy” because, Rogers says, Prince wanted it less “frantic.”

When he decided to do that, Rogers had to turn the large industrial warehouse rehearsal space of approximately 100 x 50 feet into a recording environment. Rogers described the room as long and rectangular with high ceilings and no isolation. She says Prince and the band—Bobby Z (drums), Wendy Melvoin (guitar), Lisa Coleman (keyboards), Mark Brown (bass), Matt Fink (keyboards)—set up at the short, far side of the room like they did on the Purple Rain tour, with a riser in the back.

“We just threw a nice piece of carpet on the floor and set the console in front of where the band rehearsed,” she recalls. “And I set up monitors on stands, wheeled over a tape machine, an outboard gear rack, got some snakes and got everything wired up.”

She believes it was an API console they brought into The Warehouse, as well as the Ampex MM1200 from Prince’s home. Although Rogers doesn’t recall exactly which outboard gear they used on that track, Prince’s favorites included his Prime Time digital delays, AMS nonlinear reverb, EMT 250 reverb, and before that the EMT 140 and Lexicon 480L.

The mics she used were the same as in rehearsal—a lot of Sennheiser MD 421s on guitar amps and SM 57s all around.

The keyboards were an Oberheim OB-SX and OB-X, and they used the LM-1 drum machine.

“That was the earlier version of the Linn Drum because the individual inputs on the back each had a tuning knob,” she recalls. “And on the updated version of the Linn Drum I think there were only five tuning knobs available, so you couldn’t individually tune things, and he liked tuning things separately.”

Prince came to rehearsal looking like Prince, Rogers says. “Hair immaculate, the high-heeled boots, the fine clothes,” she explains, adding that his costume designers, Louis Wells and Vaughn Terry, shared the warehouse space.

Prince played his MadCat guitar, the Hohner telecaster knockoff, with his preferred Mesa/Boogie Amps and Bag End speaker cabinets, along with what Rogers called his “secret weapon,” the Roland Boss pedalboard.

“At rehearsal, he did not like floor monitors in front because he liked to do choreography,” she says. “He loved side fills, so in the front row downstage, he, Wendy and Mark Brown were listening to themselves through side fills, as well as through their own amps, but the vocals and everything were coming through side fills. And then back up on the riser, Matt and Lisa and Bobby all had wedges. And while that was going on, those mics from the stage were feeding splitter snakes, which were feeding two consoles—a monitor mix console and the API console.”

Since the basis of the song is drum machine, Rogers says all she had to do there was push “play.” Prince and the band played live with the instruments going direct, so getting sounds was fairly easy.

Still, there was no isolation, and Rogers, who had only come to work for Prince a couple of months prior as a technician, was fairly new at this engineering thing.

She had become a technician because she wanted to be where records were being made, but she wasn’t a musician. Embarking on a career in 1978 when women were barely seen in recording studios, she decided that if she offered something badly needed, she might have a chance. While working as a night receptionist at the University of Sound Arts in Los Angeles, she overheard a teacher telling a student that a sure job was as a maintenance tech.

“So I thought, ‘That’s for me, whatever a maintenance tech is. I’ll become that so I can be in the industry.”

And she did. And she loved it and she thrived, first repairing MCI consoles and tape machines, eventually nabbed by Crosby, Stills and Nash at Rudy Recorders as their studio tech.

When she heard through the grapevine that Prince was looking for a technician, it felt like the perfect fit.

“I was a huge Prince fan,” she asserts. “I had seen him live a few times, and I listened to the same music he did—Parliament, Sly & the Family Stone, Al Green, James Brown. Soul music was the street I lived on. He liked working with women, and I was one.”

After Prince’s “1999” tour, he was about to begin the monumental Purple Rain film and album. Prince told his Los Angeles-based management team that he needed a technician who had experience with tape machines. They reached out to Westlake Audio, where owner Glenn Phoenix asked his techs if they knew anyone. Rogers’ ex-boyfriend happened to be working there, and he immediately called to inform her that her dream job was waiting.

She got the position, moved across the country, but it was a week on the job before she met Prince. She could hear him on the piano and taking meetings while she installed a new API console in his home studio (aka a small bedroom across from his master bedroom in the four-bedroom, split-level home in Chanhassen, Minn.). She also had to repair some of the tracks on his Ampex MM 1200 and some other odds and ends, until finally she told his assistant that she had completed all tasks.

Prince came into the room to survey the work and made no introductions, just asked if this and that were done.

“I answered the questions and he told me a time to come back the next morning,” she remembers of their first moments together. “He turned around to go up the stairs, and I thought, ‘I’m not going to let this start like this.’ I stopped him and said, ‘Excuse me, Prince.’ He stopped and said, ‘Yes?’ and I stuck out my hand and said, ‘I’m Susan Rogers,’ and he got that look on his face that I would see many times where he was trying not to laugh, and he stuck out his hand and said, ‘I’m Prince,’ and we shook hands and did a little bow. Okay, good.”

While their introduction may have left something to be desired, the introduction to “Let’s Go Crazy,” is legendary. Prince’s “dearly beloved” sermon for life was all part of the vocal; Rogers says she doesn’t remember if it was captured live or overdubbed later. She says Prince liked to sing live and would definitely keep the vocal if possible. The mic he used for vocals was a Sennheiser D330.

They would mix while they went along. They were recording the full-length dance versions to be edited down.

“Most of his songs tended to go for six or seven minutes, and we’d print them as a long-version mix and then cut that up and it would become the album cut,” Rogers explains. “I recorded it and tweaked a few things, and then he and I finished it together and printed it there.”

When she thinks back to the recording of that track, the greatest memory was working late into the night alone after everyone left, “finishing up some overdubs, including his guitar solo,” Rogers recalls. “Which was kinda fun.”

While the alone time was precious, there was one precarious moment that comes to mind. Rogers says that as a beginner her job was to “not mess it up,” and admits there was plenty of cortisol (the main stress hormone) running around in her bloodstream.

“I was sitting at the tape machine operating the remote in front of me, and he was playing guitar and he made a mistake,” she recalls. “So he said, ‘Roll back and we’ll punch in,’ so I rolled back to the top of the solo and I’m playing the solo and because I hadn’t done any of this, he’s playing along and I’m starting to panic, thinking, ‘Oh no, he’s recording and I’m not recording. Is he going to be mad that I’m not recording? Should I be recording?’ Yeah, I should probably record.’

“So I hit the Record button and he leaned over me and he hit the Stop button on the remote and said, ‘Who cued you?’” she continues. “I started to say, ‘I don’t know,’ and he cut me off and he said, ‘Roll back, watch my face, I will cue you and that’s where we will punch in.’ We rolled back and I watched him for the cue, and what he would do is he would be playing along and a beat or two before, he would raise up his chin and when the chin came down, that meant punch in. Over time, he and I got really, really good at that. I got really good at reading where the mistakes were, and with just the slightest movement of his head I knew where to go in. I was glad he gave me a second chance.”

The other very vivid memory of that session, she says, was how happy Prince was.

“He and the band would go over the track over and over and over again and he was just so happy,” she recalls. “He would spend a long time just going over things, not necessarily because there was anything wrong with them; the band was great, they’d get it pretty quickly, but just because he loved it so much. He would just throw that beach ball up in the air and toss it back and forth to the musicians…his joy at that time was clearly evident. That was very memorable.”

“Let’s Go Crazy” became Prince’s second Number 1 hit on Billboard’s Top 200 on August 4, 1984, remaining there for 24 weeks. It also topped the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs and Hot Dance Club Play charts.