The storied, six-decade career of Quincy Jones has been so expansive it defies description: He is a true modern renaissance man who has seemingly done it all. Initially working as a trumpeter in successful touring jazz bands led by the likes of Lionel Hampton, Dizzy Gillespie and others, he became a top arranger and producer while still a young man, writing charts and running studio sessions for an incredible array of top talents of the ’50s, including Count Basie, Dinah Washington, Tommy Dorsey, Louis Jordan, Cannonball Adderley, Ray Charles, Sarah Vaughan, Charles Aznavour and many more.

In the early ’60s, Mercury Records made him the first high-level African American executive at a major American label, and he broadened his client list to include everyone from Leslie Gore to Frank Sinatra to Tony Bennett. Meanwhile, he branched into film music with The Pawnbroker in 1964, and went on to write many memorable scores for a wide variety of films, including In the Heat of the Night, In Cold Blood, Cactus Flower, The Color Purple and even 50 Cent’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’; and for TV shows ranging from Ironside to Sanford and Son to the epic miniseries Roots. As a film and TV producer and executive producer, he’s helped shepherd theatrical features like The Color Purple and Steel; documentaries on Duke Ellington, Tupac Shakur and The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll (still the definitive series on that subject); and network series including The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Mad TV.

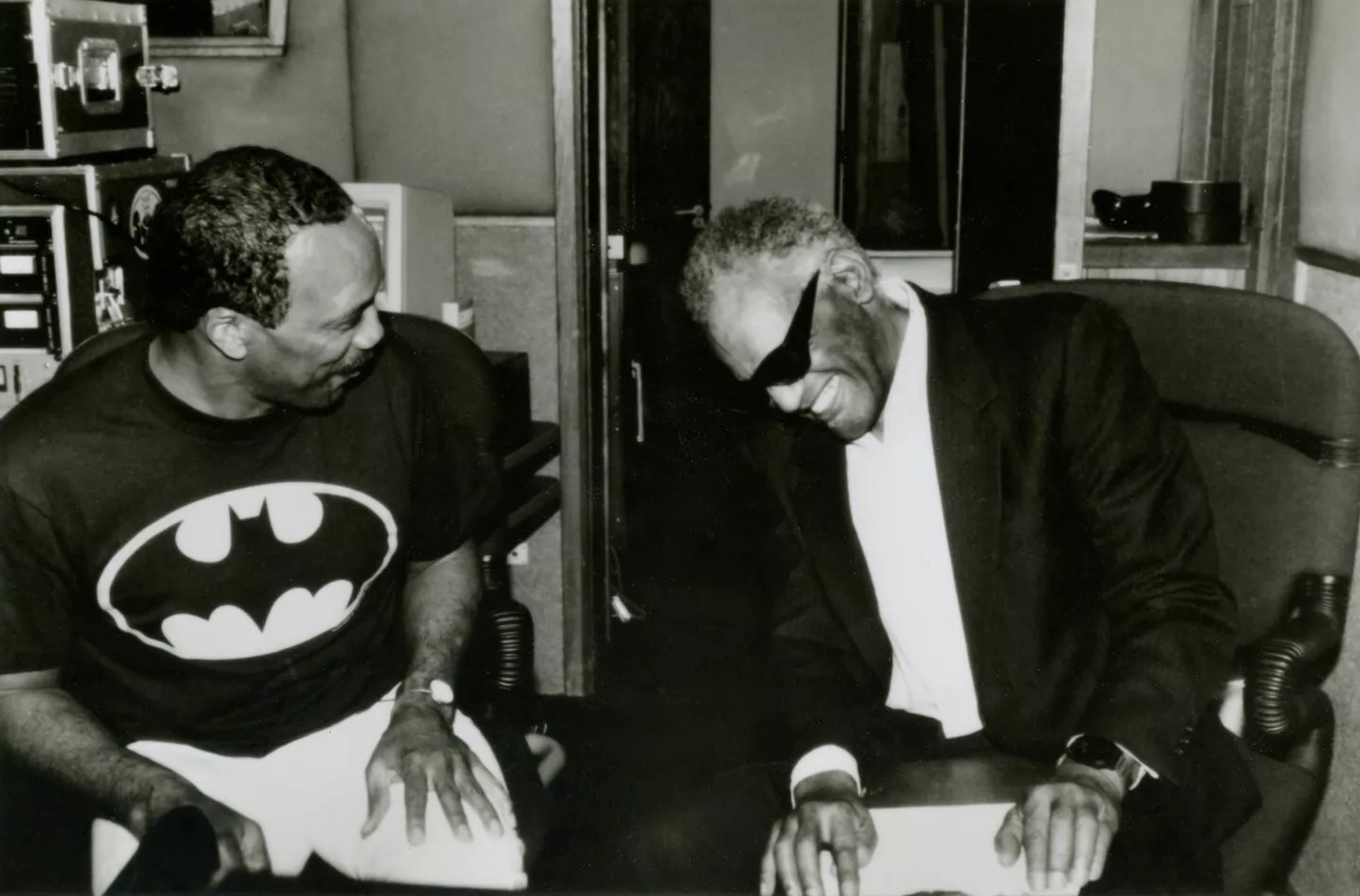

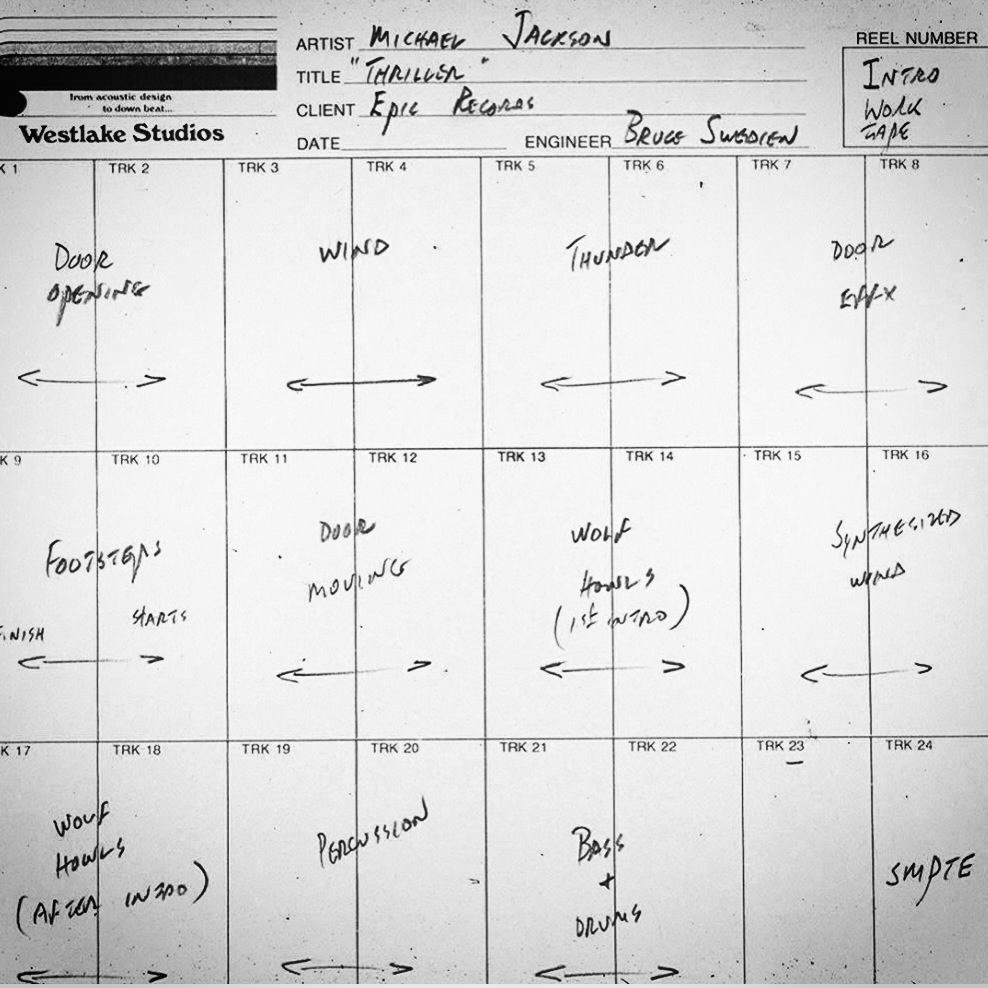

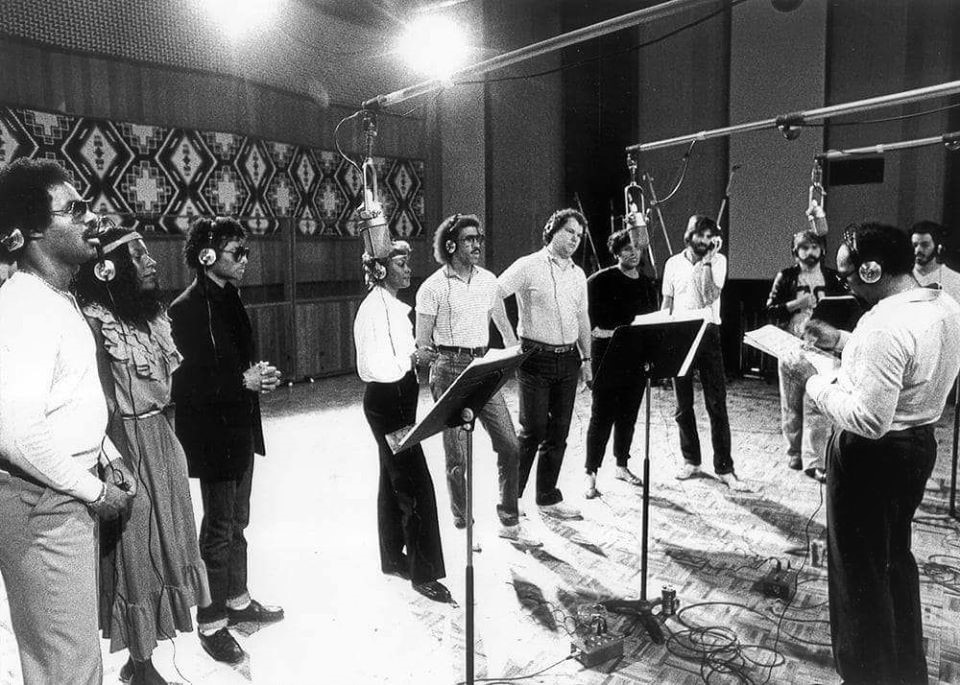

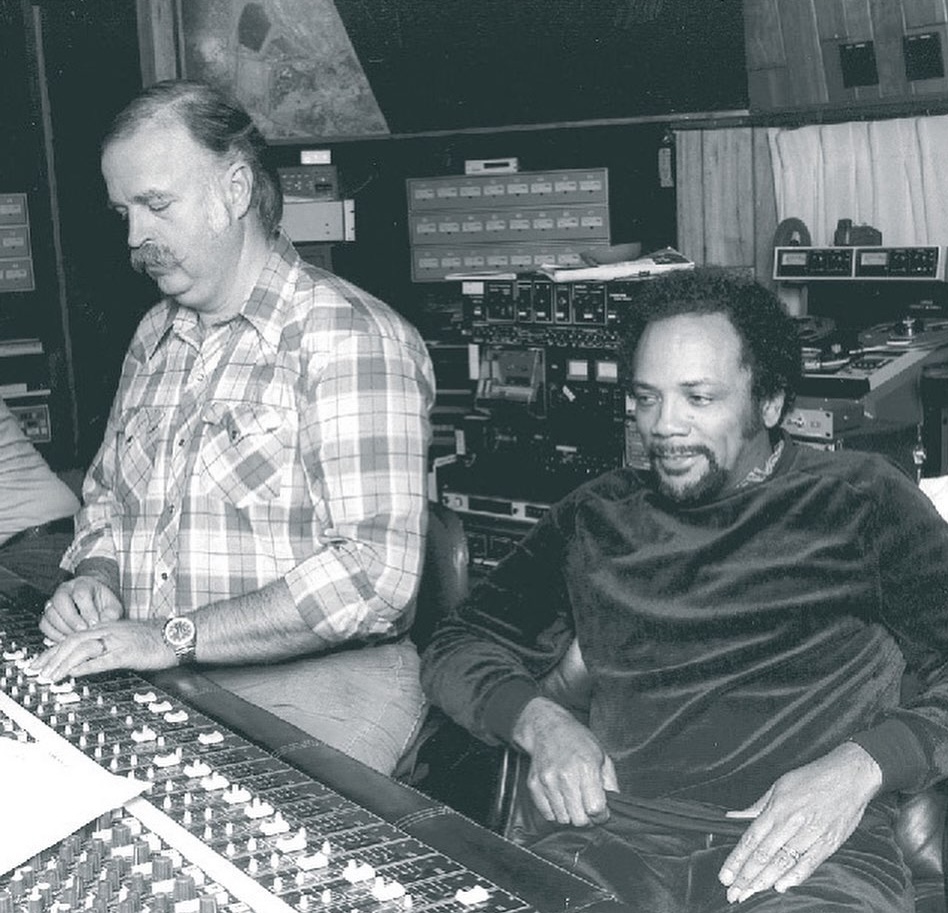

Jones had already been in music more than 30 years when he produced and arranged Michael Jackson’s gazillion-selling 1982 album, Thriller, which was also a high-water mark in his long relationship with engineer Bruce Swedien, a legend himself. Jones and Swedien’s association with Jackson also encompassed the albums Off the Wall and Bad, and included the historic 1985 all-star sessions for African famine relief, “We Are the World.”

Jones’ production and arranging career has soared as he’s bridged nearly every musical style imaginable and worked with such greats as Paul Simon, Barbra Streisand, Miles Davis, Michael McDonald, James Ingram, the Isley Brothers, Aretha Franklin and countless others. Then there’s his own recording career as a leader putting out records under his own name since the mid-’50s — again, the list long and extremely varied, including straight jazz, big band, R&B, orchestral, rap; you name it. The best known in the Mix magazine era (since ’77) are probably Roots, The Dude, Back on the Block and Q’s Jook Joint. He’s won a whopping 26 Grammy Awards as an artist, producer and arranger, and given the fact that he shows no signs of slowing down at the age of 74, he may well have several more in him.

We caught up with the indefatigable Jones in late August to talk about a few issues of interest to Mix readers. We also buzzed Swedien to get some of his insights about his longtime friend and partner in great music.

What was the first really memorable and positive recording experience you ever had?

The first one I ever did, in 1951, was with Lionel Hampton. I was 18 years old, and I’d never been in a studio before. I was in Hamp’s band, so we’d been playing a lot on the road. It was a great live band — at that time, Hampton was the biggest band out there; bigger than Louis Armstrong, bigger than Duke Ellington, Basie and all of them. He always worked. And that group was like one of the first rock ‘n’ roll bands; he had girls screaming! Louis Jordan was the other one who got that kind of reaction wherever he went.

Of course, I started with mono recording onto 78 [rpm] records. Back then, whatever you got went straight onto disk. You balanced it in the room, it had to be miked right and you couldn’t mix it the way we do now, obviously. What you heard was what you got. But a lot of those records sounded really good, and still sound good when you put ’em up against modern records.

You started out mostly as a musician and an arranger. When did you first get interested in production?

The irony of it is that all the things I’d been doing as an arranger were actually part of the production process. For instance, I remember in 1955 I called Bobby Shad — who ran EmArcy Records, which was the jazz part of Mercury Records — and I told him I’d just met these two kids from Florida, an alto player and a trumpet player, who were unbelievable; the best I’d heard since Charlie Parker. This was Cannonball Adderley and Nat Adderley. They came down to my basement and we met. I asked them if they’d recorded and they pulled out a blue-label home recording on “Frankie & Johnny” and it was one of the best things I’d ever heard in my life. I told Bobby Shad, “You’ve got to hear them!” And he said, “I don’t need to hear them — get the studio, get the musicians, write the arrangements and I’ll see you on Tuesday.” This was on a Thursday! So that was really a lot of what producing was about: knowing what engineer to call, knowing the studio — we went to Capitol Studios on 40th Street — and then figuring out tunes and arrangements. Then [Shad] comes in, and says, “Take one!” [Laughs] He was the producer; I did most of the work.

Are there producers from that period who influenced the way you worked?

Absolutely not. It didn’t work that way. I thought most of them didn’t know that much about music. They’d just come in, and say, “Take one.” A lot of producers liked music but didn’t know much. And some of them just weren’t articulate when it came to music. Then there was a guy who used to come out [of the control room] to where the musicians were, and say, “I’m hearing something.” We’d say, “What?” And he’d say, “Mmmmm.” [Laughs] It was something in the control room, I guess.

There were a few producers who knew music, like Don Costa and Hugo & Luigi and Mitch Miller, who was an oboe player. I never worked with him, but I used to go to his sessions just to learn.

It seems as though in those days, though, most were music people in some form; today, so many producers come over from engineering.

That happened back then, too, though maybe not as much. You have to have at least one core skill — whether you’re an engineer or a songwriter or musician or something — other than just being a big fan, and there were some of those, too.

Some of the engineers knew more about music than a lot of the producers. Like Tom Dowd, the legendary engineer with Atlantic Records. I worked with him a bit. In fact, I used to get paid $5 an hour to rehearse The Coasters and LaVern Baker in my basement with Ahmet Ertegun, and then Tom engineered a lot of those records.

What aspects of your personality helped make you a successful producer?

I don’t think it’s about personality. It’s about judgment.

But you have to be able to deal with people…

Of course. You’re part babysitter, part shrink. I’ll tell you what it is — it’s love. It’s loving to work with people you respect. It’s a serious love affair — that trust between a performer and a producer. Because sometimes what you’re doing is like an emotional X-ray of the human being. And when you mess with someone like Billy Eckstine or Ray Charles or Sinatra, you better know what the f*** you’re talking about ’cause they don’t play, man! They don’t take no prisoners. [Laughs] This is their career you’re dealing with.

Were you ever intimidated by anyone?

Actually, the only one who really intimidated me was Bette Davis, the actress. I recorded a song with her called “Married I Can Always Get.” I had known her so much as a movie star I was afraid to talk to her. We’re in the studio, she starts smoking a cigarette, and says, “For God’s sake, yell at me! I’m not used to people being so nice to me!” [Laughs] I said, “I’ll yell at you; no problem!” She was nervous because she was out of her arena as a singer and she got intimidated, too. But once you start talking straight to any real artist, they get it.

Did multitrack recording change how you worked in the studio?

Oh God, yes! Stereo changed things! We used to sit in Phil Ramone’s studio on 48th Street where we did one of the first stereo records, The Genius of Ray Charles, in 1958. It was all mono before then.

The hardest, a little later, was the voice-overs [vocal overdubs]. When I did Lesley Gore in 1963, Steve Lawrence had done it on “Go Away Little Girl,” but it wasn’t around much. It was hard because you had to do Sel-Sync [Selective Synchronous recording, developed by Ampex in 1955], which let you take a stereo track and then a separate mono track and manually put the two together. It used to take four hours to get one voice-over. I remember George Martin and I were friends then and we used to call each other during the Beatles sessions and we were breaking out the champagne over the phone, just happy to have gotten that one extra voice on there! [Laughs] Now, of course, you can do 200 voices if you want with no problem. But we had to figure out ways to do all this stuff.

We rode technology all the way through from 78 [rpm] discs to DATs.

As someone who cherished recording live, did you embrace the way people recorded in the ’70s, cutting the rhythm section first, isolated in dead-sounding rooms?

Sure. You have to hope for some isolation because you can’t change anything if you don’t because all the instruments are leaking into each other’s mics and you can’t fix anything and you can’t add anything. It was nice to get that flexibility.

Still, to me, nothing was better than being in the studio with Sinatra with him singing his ass off in front of a live band — it all happened right there. That was the best! A lot of people can’t handle that. A lot of singers can’t handle it — they can’t get through a whole song. But we always did whatever worked the best, whether it was recording live in the studio or recording parts separately.

If you do it right and get the performances you need, it doesn’t matter how you got there.

You have to know what you’re aiming for and [be able to tell] when you’re getting it.

When did you first work with Bruce?

We go back a long way. It was in Chicago in the mid-’50s [actually, 1958]. It was a record with Count Basie. Basie was at the Blue Note in Chicago. We also did a Dinah Washington album.

How important is it to have a good relationship with an engineer?

Oh man, are you kidding? It’s like [Steven] Spielberg and a DP, director of photography. If he doesn’t get it right, what you do doesn’t mean a thing. They capture the moment. I look at recording and producing just like a film director. The script writer is the song, the cast are the musicians and singers, and your engineer is your DP. We’ll talk, sonically, about what we’re trying to do, and Bruce will always take it further than you might think of yourself. He developed some amazing things. Like he figured out a way to use SMPTE timecode to put together as many 24-tracks as you wanted so you could get all these strong stereo pairs of everything [and not run out of tracks].

Was working with Michael Jackson any different for you because of all the pop crossover expectations that came with the gig?

Not at all. I’ve always done that. When I was 13 years old, during World War II, we were doing that in the nightclubs of Seattle with Ray Charles. We played everything: blues, strip music, R&B, pop music. Everything!

A lot of jazz people came down on me and were talking about how I was stretching out to do Michael Jackson. I said, “That’s not a stretch. I’ve done this my whole life!” I loved Louis Jordan and Debussy. Dizzy Gillespie and Sinatra. I never did one style.

Did you record much live in the studio with Michael or was it mostly layered?

Well, we had great rhythm sections, which we did first. We did what we called Polaroids. We must’ve looked at 600 or 700 songs. When you get a song you feel you like, you put it down with a rhythm section to get it on its feet, and then you hear Michael sing a couple of takes on it, maybe with a couple of background lines to see how it holds up, so you can see what it might be and you’re not just wasting your time. We called those Polaroids. Then, when something sticks, you develop it further, get into background lines and horns or synthesizers or whatever else you’re going to be using.

Was there a lot of experimentation on an album like Thriller?

Every album we did we experimented on. That’s the fun part. Bruce is a creative guy and I am, too, and so is Michael, of course. He was always up for trying new things. I remember Michael sang through these long cardboard tubes to get a particular sound — that’s something Michael came up with, I believe. But then you have Bruce there, too, knowing what every piece of equipment could do and being willing to push the limits. Everybody who was involved in those records had a hand in it. If someone had an idea, we’d try it.

You have to be open to ideas. Again, it’s like a director. Spielberg said to me when we first worked together, “This has the chance to be everybody’s film.” And to me the most powerful records come from a collective creativity. You get good records when you let all the people who work on it put their personality in their particular area. With people like [Greg] Phillinganes on piano, or [horn player and arranger] Jerry Hey, or Paul Humphreys or Ndugu [Chancler] on drums, you get a lot of feeling and soul from all the people involved.

Have you tried to keep up with technology through the years?

How can you not keep up with technology? You sit in there watching the best guys in the world and you’re going to learn. It’s important to know what the vocabulary is in whatever you’re doing. If you don’t, you’re very limited. But, obviously, Bruce can go inside there and take all the stuff out and then put it back in; I’m not into that. But at least understanding what everything does is important.

When it’s your own album that you’re working on, is it hard to wear all the different hats? Producer, arranger, artist?

It isn’t really any different. I work with people I respect and with a team that works together a lot who all care a lot about what’s up. One thing you don’t want around you is a lot of yes-men that tell you everything is great all the time. That’s bullshit. I want everyone to always feel free to say what they think. You weigh it and see if it’s valid. A film director does the same thing.

Do you still get the same rush in the studio you did when you were 18?

Absolutely! I love recording studios. That’s why I never had a studio in my home — to me a recording studio is a sacred, hallowed place. I used to have a saying: “Let’s always leave some space to let God walk through the room.” Because you’re looking for very, very spiritual and special moments in a studio. It can’t be just some place you hang out in and take for granted.

Are you worried about the future of the recording industry?

I’m worried about the distribution system, not the industry so much. Sometimes I worry about the audience being dumbed down a little bit musically. That part I don’t like. I think especially American kids need to know more about the evolution of music and where the power in music comes from. I always say it’s easier to get where you’re going if you know where you came from. Every major artist in R&B has always been connected with jazz. Jazz is like the classical music of pop music.

How can we get kids interested in jazz?

Give them a copy of [Miles Davis’] Kind of Blue. I’ve given hundreds away. I say, “I want you to take this every day, like it’s orange juice.” Listen to Miles and Coltrane and Bill Evans and Cannonball. It’s very important, because from Marvin Gaye to Donny Hathaway to Earth, Wind & Fire to Stevie Wonder to Michael Jackson, they all owe a debt to that tradition. Take a close look at “Baby Be Mine,” the Rod Temperton song [on Thriller]. Rod is a genius. It goes [he scats], “Deedle, dee-do-dee-dee-dee…” That’s Coltrane, man. It’s got pop lyrics and a beat, but it’s Coltrane. It all came from the same place.

And this music has been adapted by the entire planet. I’ve been around the world three times in the last year and a half, and everybody is playing that music — in most cases, pushing their own indigenous music aside to play our music. And guess who knows the least about our music? Our kids. I used to talk to Clinton and Gore about why we don’t have a Minister of Culture. I got promoted to Commander of the Legion of Honor in France [in 2001]. They really care about that stuff over there, and it’s crazy that a country like ours — that is emulated all over the world — doesn’t have a Minister of Culture. And there’s nothing going on in the schools, culturally.

In fact, they’re cutting music in schools.

That’s right. In Russia, from second grade all the way through university, they’re studying [Dmitry] Shostakovich, [Nikolai] Rimsky-Korsakov, [Igor] Stravinsky. They’re studying the Germans, like [Arnold] SchÖnberg, and our music. Europeans play jazz better than Americans do. It’s a joke.

If you were going to recommend a few albums of your own music to people who might not be familiar with music you’ve written, where would you begin?

That’s a tough one. Maybe The Dude [a 1980 disc that helped make James Ingram a star], Walking in Space [a great big band album loaded with top jazz players from 1969], Back on the Block [1989]. Back on the Block covers almost everything from the 60 years I’ve been in music, from gospel to Zulu music to bebop to hip hop. Sinatra at the Sands [a classic 1966 album of Sinatra and the Count Basie Orchestra, arranged and conducted by Quincy] was another of the great musical experiences of my life. “Fly Me to the Moon” was the first thing I [arranged] for Frank.

How much do you still write today?

I’m getting ready to do a piece I’ve been working on for something like 28 years. We may do a Cirque du Soleil thing with it. It’s the genesis and evolution of jazz and blues, all the way from Africa, the Spanish Inquisition, the Moors, the middle passage, Brazil, Haiti, Puerto Rico, slave ships in Virginia.

You’ve been such an important guardian of African-American music and culture. Few people have attempted to tie it all together the way you have.

For me, it comes very naturally because I love all these types of music so much. Wynton’s doing something with Willie Nelson now. It’s all part of what I call the global gumbo. It’s been great to see.

Bruce Swedien on Quincy Jones

Engineer Bruce Swedien and Quincy Jones first worked together on a project at Universal Recording in Chicago in 1958, and through the years they’ve made great music together dozens of times, even as each has worked on literally hundreds of other projects separately. “I have ultimate respect for Quincy, on a musical and personal level, and I think he feels the same about me,” Swedien once wrote in tribute to his good friend. “Quincy Jones is the kind of friend you could call in the middle of the night, with your most personal problem, either real or imagined, and he would come to your rescue…In addition, almost everything that I treasure, that I know from recording good music, I have learned from my pal Quincy Jones.”

Reached by phone, the jocular Swedien is happy to talk about his long-time friend, “but I want you to mention prominently that he and I are nearly the same age — I’m 13 months younger!

“Quincy has always been a completely amazing guy,” he continues. “It’s not like he slowly became the person he is. Back when he was with Mercury Records, as the youngest vice president at a major label and also the only African American, he was kicking ass, just doing great work. He was pretty much unstoppable.”

Swedien credits Quincy with being an early, important supporter of stereo records at a time “when none of the major labels believed in it. Stereo in the late ’50s was almost a strangled infant in the crib, but Quincy believed in it and pushed it. At every step along the way, Quincy has been for whatever innovation has come along.”

Of course, Jones and Swedien will forever be linked in the public mind for their work with Michael Jackson, and on that matter, Swedien comments, “What made that so good for me is I got nothing but total support from Quincy and Michael. I was trying all sorts of different things in the studio — like having Michael step back a few paces for the overdubs and doing a double pass to get the early reflections as part of his image, which nobody else was trying. No matter what I tried, Quincy and Michael were always saying, ‘Do it! Go for it!’” That included Swedien working up 91 mixes of the song “Billie Jean.” “We had half-inch tape up to the ceiling,” he says, “and, of course, the one we eventually chose was mix 2!”

Swedien says he remains in awe of his friend’s far-reaching talent and notes again that it was apparent from the beginning of their association. “An important part of his biography is that he studied with [composer] Nadia Boulanger in Paris [in 1957], because it says a lot about Quincy’s musical standards, which are extremely high, and always have been. That’s a real key.

“What can I say? Quincy is Quincy. He’s one guy who really changed music. Of all the people I’ve worked with — and I’ve worked with everybody — I would say Quincy’s closest comparison in music would be with Duke Ellington. I did a lot of work with Duke Ellington, and like him Quincy’s instrument is the orchestra; there’s a real parallel there. But also having talent in so many areas. It is so rare to find that.”

— Blair Jackson