It’s a scorching August afternoon in Italy when Rick Rubin gets on the phone to New York. “It’s kind of late in the day here and it’s super hot, so I’m trying to just lay low,” he chuckles—which means it’s a perfect time to talk about the latest album crafted in his California studio. The record in question is This Is How Tomorrow Moves, the third album by singer/songwriter Beabadoobee (referred to as Bea), who traveled halfway around the world from her home in London to record at Rubin’s fabled Shangri-La in Malibu.

“Bea’s delightful to be around, she sings really great, she was extremely hardworking,” says Rubin, thinking back to the six-week session last fall. “I don’t think I would’ve predicted that the album would sound like it did. It’s probably much more of a rock album than I would’ve guessed… but it was not an intentional decision, at least not on my part, to push it in that direction. It just went where it wanted to go.”

Of course, where everyone involved really wanted it to go was the top of the charts, and a few weeks after the conversation with Rubin, that’s exactly what happened. This Is How Tomorrow Moves, a showcase of assured, mature songwriting that recalls Crowded House one minute and turn-of-the-millennium dream pop the next, debuted in mid-August to strong reviews, and a week later entered the UK’s Official Albums Chart in the top spot—her first Number One.

For Bea, it’s a long-awaited but hard-earned victory. The English-Filipino singer has been gaining momentum ever since she took the first song she wrote on guitar, “Coffee,” and posted it to YouTube in 2017. “It’s quite funny,” she says now. “I was actually recording with a really crappy mic; any odd mic with a sock on top of it. That’s how I was recording all my songs.”

If the audio quality was questionable, the musical talent was not. “Coffee” went viral, more home recordings followed and six months later, Bea, then only 17 years old, was signed to indie label Dirty Hit. A string of increasingly successful EPs and albums followed over the next few years, amassing more than 5 billion streams in the process, and that in turn paved the way for opening a dozen shows last year on Taylor Swift’s Eras tour.

“Bea’s had an incredible journey,” says Rubin. “She recorded one song in her bedroom, put it up, and was instantly recognized from the first thing she ever recorded…. I loved hearing the story because I’ve never been around artists who have come up that way.”

Of course, Rubin’s been around virtually every other sort of artist during his own one-of-a-kind career, founding both Def Jam and American Recordings, working as co-president of Columbia Records for a time, and becoming the go-to record producer for a who’s who of popular music: Red Hot Chili Peppers, Adele, Black Sabbath, Johnny Cash, Slayer, Jay-Z, Mick Jagger, Public Enemy, The Cult, Tom Petty, Sheryl Crow, Run-DMC, System of a Down, Kesha, Coheed and Cambria, Metallica, Beastie Boys, Poison, Linkin Park, U2, Weezer, Lady Gaga, Kanye West, Eminem, Josh Groban, The Avett Brothers, LL Cool J, Lana Del Rey, Ed Sheeran, Santana, The Dixie Chicks, Imagine Dragons, The Strokes, Neil Young, Travis Scott, Smashing Pumpkins and the list goes on and on.

Rubin worked with many of those artists at Shangri-La, and it was there that Bea and longtime collaborator Jacob Bugden found themselves last November, far from home but determined to make an album that would take her career to the next level.

![Shangri-La’s well-stocked mic locker includes Neumanns and more. Photo: Jake Erland. [Beabadoobee rocking the mic]](https://www.mixonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/2024-09-24-RickNBeaBea-21.jpg)

THE ROAD TO SHANGRI-LA

Deep in Malibu, just above Zuma Beach, the 1.74-acre plot that became Shangri-La had a colorful history long before it became a studio. Built in the late 1950s, the main house was built for film actress Margo, who named it Shangri-La Ranch as an allusion to her role in the 1937 classic, Lost Horizon. As the years wore on, it became a film location for the 1960s talking-horse sitcom Mister Ed, and later, according to The Band’s Levon Helm, a high-end bordello catering to Hollywood.

All that changed in 1974 when The Band, fresh off the road from a tour with Bob Dylan, leased the site so they could have a place to hang out and record 1975’s Northern Lights – Southern Cross. Producer Rob Fraboni was brought in to convert the master bedroom into a 24-track studio (he later bought the facility in 1976), and soon fellow rock royalty like Ringo Starr and Eric Clapton started showing up to chill out. Shangri-La became a magnet for musicians looking to kick back and unlock their creativity; music began pouring out of the place, interviews for Martin Scorsese’s documentary The Last Waltz were filmed there, and Dylan himself took up residence in a teepee on the lawn (his former tour bus, now remade into a secondary studio space, still sits abandoned behind the house).

“I can remember the first time I was there with Neil Young,” says Rubin. “We were sitting in the control room, and I asked him, ‘Did you ever get to come here in the ’70s?’ He pointed to the live room and said, ‘The day I wrote “Cortez the Killer,” I came here, sat in that room, sang it for Bob and that was the first time I ever played it.’ It was just like, ‘What?!’ It’s so much to process that these things happened there—it feels like it gives it a sense of a holy place, like a church of music.”

Elaborating, he explains, “With these places, if artists come to the same place for a long period of time, it’s almost like, energetically, there’s some draw where it just feels good to be there. So much great music has been made there over the years that when you go there, even though it’s relaxing and beautiful and peaceful, you still know this is where serious stuff happens.”

Rubin was completely unaware of Shangri-La’s legacy, however, when he first booked a few Weezer sessions there in the mid-2000s. By then, the studio had changed hands a few times and fallen into disrepair; bookings had grown scarce, and the facility was on the verge of shutting down like so many L.A. studios during that era.

“It was just a convenient place because I was living in Malibu, it was close to home, and Rivers Cuomo said, ‘I found this studio,’” Rubin says. “It was really run down and depressing—but then the things that we recorded sounded really good and it just grew from there.”

By the time Rubin acquired Shangri-La in 2011, it was in desperate need of renovation, but the opportunity to reinvent the studio came as the producer was starting to rethink some of his own approaches to life. That philosophical change soon influenced the facility’s new direction.

“It started with the way I was living,” he says. “I lived in this big, old 1920s Hollywood house filled with antiques and stuff, and I thought that was the way I would always live. Then when I got my house in Malibu, it started as an empty space and I really liked that. Instead of moving all of the stuff to Malibu, I just lived in the empty house for a long time—years and years and years. I liked it, and it felt good for the creative process mentally to not have any distractions. When I ended up buying the studio, I just took the way that I was living in the house and adapted the same sort of Zen empty-space feeling to the studio.”

Today, Shangri-La is minimalist to the max—all walls and floors are painted white, and there’s a pointed absence of typical studio trappings like awards, memorabilia, televisions and so on. While there are big windows looking out at nature, there’s not much in the way of furniture, and what little there is gets covered in white tarps to help maintain the visual neutrality. The result is that musicians find themselves working in an adamantly diversion-free environment.

“When artists come, they love it and don’t want to leave,” says Rubin. “It wasn’t premeditated, but in retrospect, I realize, ‘Oh, I see why people like this. I know I like it, but I see why other people do, too, and how different it is from their normal experience.’”

BEA HERE NOW

One artist it was different for was Bea, who arrived in Malibu well out of her element, but game to make a great record. “It was an opportunity that I would have been stupid not to take,” she says. “At times, I feel like I tend to settle a lot, and I feel comfort in making music at home and recording in studios back in London—but I felt like I needed to be pushed, so going to Shangri La was a big step for me. It was very daunting; working with Rick was intimidating at first, but I think within the first 24 hours, I came to realize this was the best decision I could’ve made.”

Some of that initial concern came from the supernally white surroundings. “I’m a maximalist in the way I like my house and like things aesthetically,” says Bea, “so walking into the studio, it was, ‘Oh, my God, it’s a blank canvas!’ I soon realized, ‘Oh, this is perfect for what I need right this second.’ All you have is your creativity, all you have are your thoughts, and you want to fill that space with the music.”

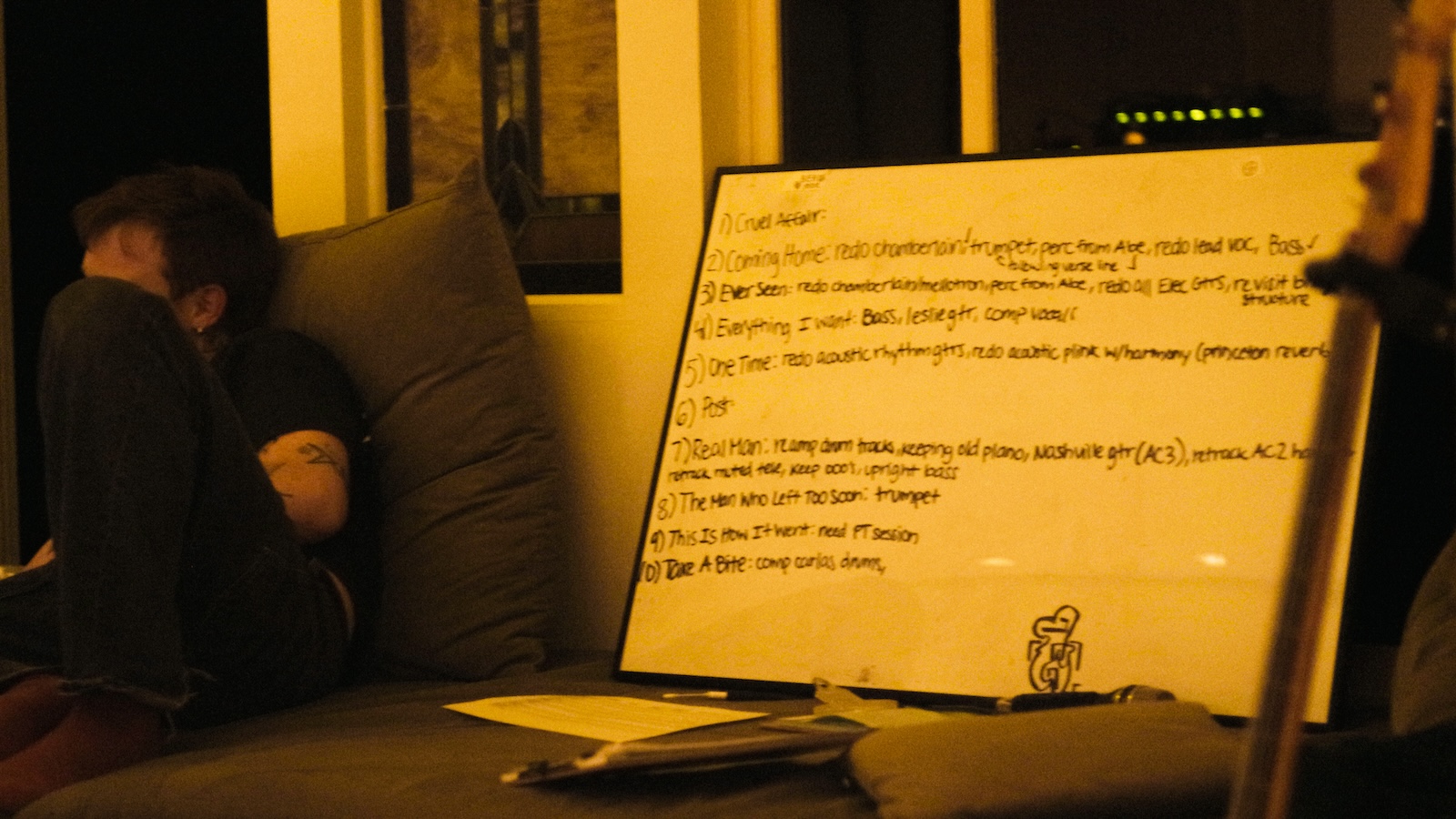

Music was something Bea had a lot of, having spent two years writing at home and on the road as she chronicled moving on from a difficult breakup. While Bea and Budgen were excited to share their painstakingly recorded demos with Rubin, however, the producer caught them off-guard with a request.

“My first suggestion was to go in and record all of the songs stripped down—solo guitar, just her or Jacob playing, and her singing,” says Rubin. “I wanted to hear the strengths and weaknesses of the songs, because sometimes you can use a production trick that’s really exciting and get fooled into thinking that the song is better than it is when really the production is what’s carrying it. The best is when the song carries itself and then the production makes it the coolest record.”

While the request came as a surprise, it turned out to be the moment that changed everything. “Playing the entire album acoustically—which is basically how I wrote it in my bedroom—was when I found confidence in my own songwriting, which I’ve always really struggled with,” Bea says. “That’s when I realized, ‘Oh, minus the instrumentation and all the beautiful production sounds we made, this is still a song that I could potentially release like this. There is a beginning, middle and end—and I love this song.’”

Bea and Rubin also found a common middle ground in their unassuming approaches to music. “I think what I really go off with, and what Rick really goes off with, is what you feel and the vibe and what you hear,” says Bea. “I can’t play piano and find the key of the song; the way I play guitar, every time I play with a session musician, they’re like, ‘What the fuck are you doing? What chords are you playing?’ They’re always like, ‘It sounds pretty, but that chord does not even exist!’ I don’t really follow any rules.”

Rubin, for his part, is similarly modest, remarking, “Yeah, I don’t know if ‘professional’ would be the word I would use for anything I’ve ever been involved in. I come from a punk rock background and have made some of the most, let’s say, naïve-sounding recordings that you can find.”

While Rubin downplays the professionalism of his recordings, he has a track record—not to mention a literal Shangri-La of enviable vintage gear—that says otherwise. Although there’s a second studio on the premises in a chapel-shaped bungalow called, yes, The Chapel, the main studio, where Bea and Bugden recorded, still has the original API 32 x 48 console first installed in 1975. The desk is surrounded by a playground of often vintage gear, ranging from API 550A EQs and Neve 1073 and 31102 mic pres to Fairchild 660 and 670 tube compressors, an RCA BA-6A limiting amplifier, old-school LA-2A and LA-3A compressors, Pultec EQs, a 1960s EMT 140 plate reverb, Roland Space Echo and Binson Echorec delays, and lots more.

Vocal microphones on-hand include likewise vintage Neumann U67s and RCA 77-DX ribbon mics, but not everything in Shangri-La is old; playback is heard through ATC SCM25A studio monitors, a pack of Audio Kitchen stompboxes are at hand for re-amping instruments, and a Tree Audio Roots Senior console is used for its tube pres on drums and bass. Naturally, numerous cool guitars stand at the ready, and there’s also a rare Chamberlin keyboard, a precursor to the Mellotron that lets users essentially play samples on tape.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Rubin finds the vibe or feel of instruments and gear far more important than their pedigree. “I’m pretty flexible with equipment,” he muses. “If something doesn’t sound good, I might say, ‘Well, what did we use last time that sounded good,’ but that’s as far as it goes technically. It’s nice when there’s a really good-sounding piano in the studio; that seems to matter a lot.”

WE DIDN’T SETTLE

Throughout the recording process, Bugden was a crucial element; in addition to co-producing the album, he provided backing vocals, guitar, bass, keyboards, programming and drums, in addition to engineering every track with Jason Lader and Callum Waddington. As recording progressed, Bea, Bugden and the rest of the team fell into a routine of hitting the studio around 10 a.m. and working on and off for the next 12 hours, breaking regularly to swim in the November waters of Zuma Beach. “It was like a cold plunge!” says Bea. “Every time vibes were getting low in the studio, we all just jumped in the sea, and then we could work for even longer, which is amazing.”

The serene surroundings inspired a new song written in the studio, “Beaches,” which alludes to the calm and focus found at Shangri-La: “Days blend to one when I’m on the right beaches / And the walls painted white, they tell me all the secrets.” Still, the arrival of a new tune didn’t push anything else off the To-Do list.

“I strongly believe in recording everything,” says Rubin. “I can remember with one or two songs in particular, she said, ‘These are not as good as the newer ones; let’s not record them,’ and through the recording process, they became some of her favorite songs—but you don’t know that in advance! I think accepting the fact that we know so little about what makes something good gives you a great ability to try things freely. It’s about taking all of the ego out of it and starting with, ‘I don’t know what’s good until I hear it, and when I hear it sounding good, then I know it’s good.’ Thinking about what’s going to sound good doesn’t really tell you anything.”

Many of the songs kept evolving throughout the six weeks at Shangri-La. “I remember with a song called ‘One Time,’ Rick came in and there was this one bass note that was really sticking out for him,” says Bea. “It was sticking out to him so much that he had to leave the room! So we stayed in the studio and ended up doing a bass riff, and it brought ‘One Time’ to life with this groove that it didn’t have before—so I always think the way he works like that is very interesting.”

Elsewhere on the album, “Girl Song” was recorded twice, first as a full-on rocker and then as a stripped-back piano ballad. “It sounded really good as a big rock song,” says Rubin, “but the emotion of the piano-based version was just more interesting—and we had no idea about that in advance.”

The important thing, he says, is that no stone was left unturned: “Sometimes you make it better and sometimes you can’t…and that’s great, too, because we know we did the work. We weren’t lazy about it. We didn’t settle. I remember the first song we mixed for [Tom Petty’s] Wildflowers was ‘It’s Good to Be King,’ and we did a rough mix in Mike Campbell’s studio just to get a sense of the song. In the whole process of mixing the record and going to better studios, it never was better than that first quickly done rough mix, which ended up being on the album.

“You never can tell which is the one that’s going to speak to you. I think one of the things that you learn from doing this for a long time is that just because you work on it longer and just because you put more time or money into it, that doesn’t make it better. It can, but also it doesn’t mean anything. At the end of the day, if you blindly listen, whichever one speaks to you, that’s the one to share with the world.”

How Freddy Wexler Created ‘Turn the Lights Back On’ with Billy Joel

And now the world is discovering the songs that speak to Bea, Bugden and Rubin. The recording process left them certain that This Is How Tomorrow Moves would work, but debuting at Number One? It’s a turn of events that the artist herself can’t quite believe when Mix catches up with her on the day the UK chart is released. To say she’s ecstatic is probably underselling it.

“I actually found out yesterday, and they gave me the award yesterday, and I couldn’t tell anyone, and then I had to go and play a show, and all I wanted to do was just tell everyone how much I appreciated all their support on the record, but I couldn’t, so I just cried on stage,” she blurts, laughing. “I was like, ‘I wish I could tell you why I’m so happy,’ and then I just started crying during ‘Beaches.’” More laughter down the phone line. For Bea, tomorrow is going to move just fine.