New York, NY (September 4, 2024)—Billy Joel has always come across as a regular guy who just happened to sell 160 million records, but the dozen studio albums he released between 1971 and 1993 tell a different story. Sure, they’re packed with Top 40 hits—33 of them—and well-known album tracks like “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant,” but even a casual listen reveals he was a craftsman working at the peak of his powers. Engineer Bradshaw Leigh can attest to that, having spent much of the last two years analyzing and remixing seven of the Piano Man’s albums into Dolby Atmos.

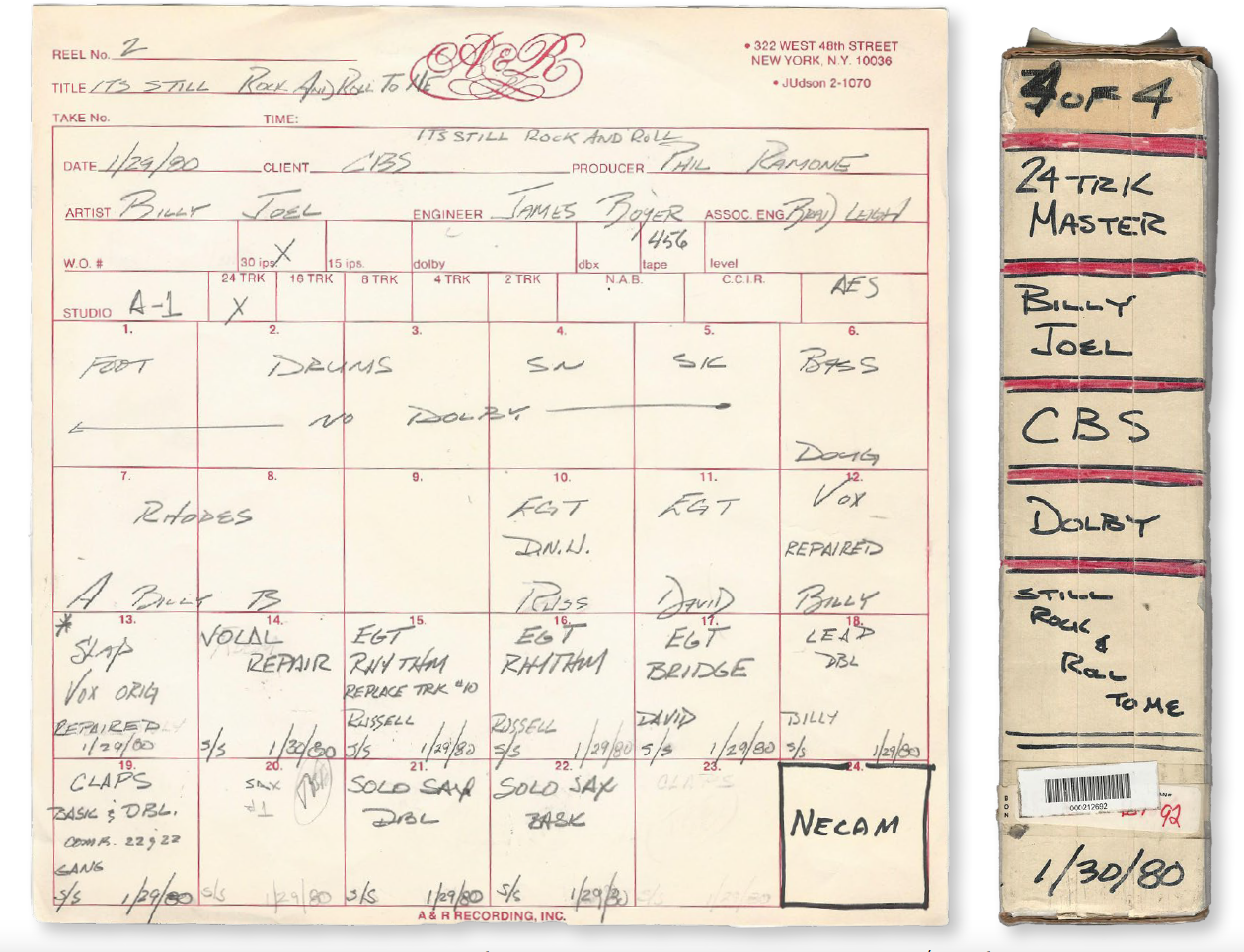

While he’s spent his career working with everyone from Tracy Chapman to Joe Jackson to Five for Fighting, the immersive mixes are an unusually personal project for Leigh, as he was there when many of the albums were first recorded, having worked on nearly every Billy Joel record from 1980’s Glass Houses through 1993’s River of Dreams. Leigh got his first real break when he started working as a night tech in 1978 for legendary producer Phil Ramone’s A&R Recording. Within a year, he became an assistant engineer for Ramone and head engineer Jim Boyer, and graduated to associate engineer by the time Joel began working on 1982’s The Nylon Curtain. A full 40 years later, Leigh returned to Joel’s moody statement album to remix it for Atmos—and it was his first spatial audio mix ever.

“In hindsight, I started with Mount Everest!” he says with a laugh, sitting in the Atmos mix room of Manhattan’s 2nd Story Sound. “It was Billy’s most experimental record, so a lot of stuff was thrown on tape that wasn’t used, and that had to be sorted through. Also, he was going through a whole Beatles-esque thing, so there’s a lot of crazy effects that had to be re-created. I asked Sony to dig through the archives for the mix notes and only got a couple of pages for one song, so it was a real forensics project.”

The sparse notes confirmed a few things that Leigh remembered, including some of the outboard effects units that were used, such as an Ursa Major Space Station, a Lexicon Prime Time Digital Delay and a 224 Reverb. Modern-day plug-ins easily replicated those items, and sometimes he found that getting close enough worked just fine: “The album was mixed on a Neve 8068 console, so I got the Lindell Audio 80 plug-in, which is like a 1084—very similar to the equalizer that was used when we were mixing.”

Sometimes, however, similar wasn’t enough: “When I did the first mix of ‘Goodnight Saigon,’ I sent it to Billy’s team—John Jackson, Steve Cohen and Brian Ruggles. John came back and said, ‘It’s brilliant, perfect—except Billy’s vocal isn’t quite icy-sounding enough.’ There was one note on the track sheet for that song, and it said ‘25 ms, Eventide Harmonizer,’ so I pulled up a delay plug-in, put 25 ms on it and I was real close—but it wasn’t right. The Eventide plug-in bundle had just been released, so I bought it. Back when we recorded the album, we only had the 949 in the studio, so I called up ‘Harmonizer 949,’ set it on 25 ms, and there it was! I was really shocked how going from one plug-in to another would have that effect, but it’s just the algorithm of that original device.”

GO WITH THE WORKFLOW

Since handing over the completed Nylon Curtain Atmos mix, Leigh has been invited back to remix Piano Man (1973), Streetlife Serenade (1974), Turnstiles (1976), 52nd Street (1978), Glass Houses (1980), and An Innocent Man (1983); in the process, he’s developed a workflow that leaves room for both creative and detective work.

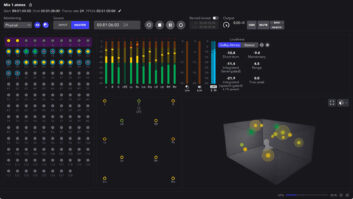

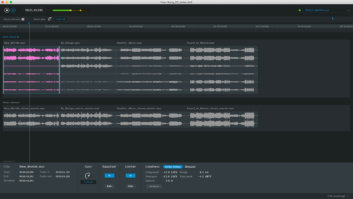

“Some engineers work entirely on speakers and others mix it all on headphones; I think there’s a price you pay for that,” he says, adding that he uses a combination of both. Typically spending three days per song working in his home studio, Leigh starts by using the original multitracks to replicate the existing stereo mix, listening through tri-amp speakers he custom built.

“I do everything I can to duplicate the stereo but get it more detailed, more hi-fi, more open,” he says. “For me, trying to compare stereo to Atmos from the get-go would drive me nuts, because you can’t get the subtle placements and relationships. When you match the stereo, the closer you get, the more it reveals what you’re not doing right—‘Wait a minute! On the record, the chorus is different; where’s that guitar that thickened it up?’”

Replicating the stereo mix is also where the detective work begins, he explains: “If there’s five passes of David Brown playing the same guitar part, which one is right? I’ll kill the center of the mix and listen to the sides to see what I can hear with it panned up. I look for details like ‘Oh, on this track, he anticipates that beat,’ and then go back to the stereo and compare.”

How Freddy Wexler Created ‘Turn the Lights Back On’ with Billy Joel

When the replicated stereo mix is in good shape, Leigh moves to headphones and starts building out his new stereo mix in Atmos. “I’ll start with a stereo reverb on the voice and a stereo ambience, and then with LiquidSonics, I duplicate that as a quad reverb in the back of the room,” he says. “I have a balance control between the front and back stereo reverb on the voice, so I can move the effects forward and back, and I’ll take the ambience on the voice and move it to the ceiling so it’s not coming out of the front.

“Once I get a lot of that structure, I come to 2nd Story Sound and work on speakers. Things can change when you do that—maybe some pannings don’t work quite as well or certain things aren’t as prominent. Also, when you’re mixing on headphones in Atmos, if you take an instrument and pan it to the ceiling, it gets brighter, or move it to the back wall and it gets darker—but that doesn’t happen when you hear it on speakers. So I get the mix where I want it on speakers, then I go back home to my headphones and listen to it. If I’ve done something on the speakers that has diminished the headphone mix, I’ll try to compromise or dial it back, because I think most people are listening on headphones.”

DECONSTRUCTED PIZZA

In the process of replicating the original stereo mixes, Leigh discovered many of them were surprisingly tight and condensed, which sometimes led to conservative panning in his Atmos translations.

“I know 5.1 guys love everything panned to different speakers, and I do too, but I won’t do it if it’s gonna mess up the song,” he says. “A lot of times, I felt the mix wanted to be clustered. You pan stuff out and suddenly you’ve got four equal partners; you don’t have a song. It’s like getting a deconstructed pizza at a high-end restaurant where there’s a piece of cheese here and a tomato there and then there’s a piece of bread—and that’s not a pizza!”

Of course, with pizza, a tasty tomato sauce can cover up some questionable ingredients, and the same goes with a mix, where pulling things apart occasionally reveals aspects best left hidden. “A lot of Phil’s arrangements are in the mix,” Leigh notes. “I’ll be listening to a mix, hear strings in it, then I’ll hit another section, everything’s blasting and I can’t tell if the strings are there. I’ve caught Phil turning off the first and second violins and leaving the celli, so it’s like, ‘Did he take them out or are they just really low in the mix?’ Let’s say I take the strings and pan them to the rear, which I like to do a lot. Suddenly you might hear in the chorus that the strings have a melody that you haven’t heard before—and it ain’t that great.”

Other times, an instrument is practically begging to be prominently featured in the mix but making that happen is still the wrong move. Remixing the early single “The Ballad of Billy the Kid,” Leigh wanted to highlight the dramatic guitar line that powers the intro and repeats later on. “That song had a mono piano, so I pulled it over to the right to give it a little spread,” he says. “The guitar in the stereo had been on the right, and now I thought, ‘I’ve got all this space on the left and that guitar line is a big line—I’ll move it there!’ I moved it and discovered that as soon as it goes into the verse, he’s chugging, playing chords on a chorus pedal that you never really heard—so I had to put it back behind the piano, because it’s doing its job; it’s gotta be there.”

Bringing each Billy Joel album into Atmos was its own challenge. Replicating the stereo mix of 52nd Street, Leigh found the original had an overly forceful midrange even though the multitracks weren’t as aggressive. While not to his own taste, matching it meant replicating that forcefulness. Something similar happened when he began mixing the hit “Allentown” from The Nylon Curtain: “It starts with the sound of a pile driver, and I was, ‘Great! I’m gonna fix that out-of-time pile driver that’s been driving me nuts for decades!’ I get the track—and the pile driver’s in time! There’s a delay added that gives it that ‘G-G-Gh!’ Jim Boyer did that on purpose when he mixed it… so I had to duplicate that frickin’ delay on the pile driver.”

That dedication to faithfully reproducing an album’s original sound is part of what makes Leigh’s Atmos mixes feel both familiar and newly energized at the same time. While he made the occasional creative change (“On ‘Piano Man,’ the accordion’s too loud, but man, it sounds good!”), the resulting mixes sound as if they were always meant to be heard in Atmos.

“If I can have fun things happen and make it sound better, and you think you’re still listening to the same record, I’ll do it,” says Leigh. “My big thing is that it has to honor the artist’s and the producer’s original intention. Phil Ramone’s not with us anymore, but he’s still standing over my shoulder.”