This interview appeared in the December, 1998 issue of Mix.

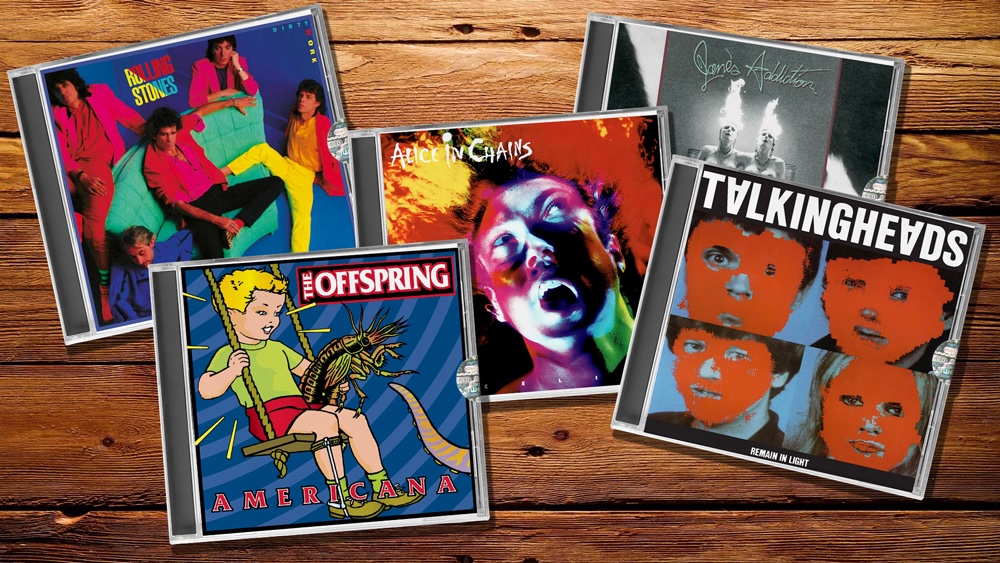

A quick perusal of his credits shows that Dave Jerden has worked on a lot of really cool records. He blends a bit of the purist with the iconoclast, and he’s assembled a discography that cuts a wide swathe through musical styles. One of the very first engineers to use samples (Jerden was recording and mixing engineer on Herbie Hancock’s groundbreaking 1984 album Future Shock and its hit single “Rockit”), he was also the guy behind the board for that unforgettable moment when the guitars come slamming in on Alice In Chains’ “Rooster” from 1996’s Dirt.

A few other highlights: Jerden was the recording and mixing engineer on Talking Heads’ Remain In Light and David Byrne and Brian Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and the producer/mixer of Jane’s Addiction’s Nothing’s Shocking and Ritual De Lo Habitual, Social Distortion’s Social Distortion and Somewhere Between Heaven and Hell and The Offspring’s Ixnay on the Hombre. He has also worked with Frank Zappa, Tom Verlaine, Jane Child, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Anthrax and the Rolling Stones.

Legendary Rock Producer Dave Jerden Passes

A previous interviewer called Jerden a “sonic bricklayer,” an apt description that conveys his unique blend of skills—artistic, yet all business. He’s a guitar-loving rock engineer who is also totally comfortable with technology. In person, he comes across as intense, highly creative and quite serious, with a demeanor rescued from severity by frequent flashes of dry humor.

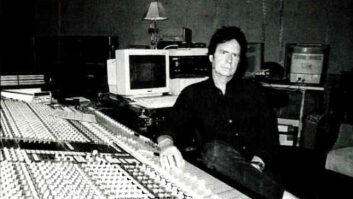

He’d just finished mixing The Offspring’s latest release, Americana, when we found him at El Dorado, his Los Angeles recording studio of choice. It’s an industrial, warehouse-type space, and the control room was equipped with three separate computer rigs, a super-sized roadcase packed with guitar amp heads, and a second wall-sized roadcase filled with Summit tube gear. As we talked, Jerden seemed to be in constant motion—opening road cases to display a piece of gear, paging through screens on a computer, pacing out to the studio to point out a detail. Even in repose, he emanates a considerable energy field.

Mix: Did you start out as a guitar player?

Dave Jerden: Guitar and bass; I started playing in bands when I was 12. My father was a bass player, and he encouraged me. Most kids, when they get their first guitar, it’s a piece of crap.

But when I took an interest in playing guitar, my father bought me a really nice Gibson. Then, when I had an opportunity to play bass in a band, he bought me a Fender Precision bass. I played in bands early on, not because I was any good, but because I had good equipment.

Did you take lessons?

For a few years. My dad was always trying to push me toward heavy reading—he had goals for me to be a jazz musician.

Wait a minute. Nobody’s parents’ goal is for their kid to be a jazz musician!

I was really fortunate. All along the way, I had encouragement from my family. And when I crossed over to engineering, they were also totally supportive.

How did you make that transition?

I wasn’t making any real money as a musician. I was in a band with Eddy Schreyer, who has Oasis Mastering now, and he went to engineering school, so I decided to try it. It was called the University of Sound Arts; it wasn’t any great shakes, but one thing I learned there was what books to read. I bought this one book, Modern Recording Techniques, by Runstein, and I memorized it. I figured if I knew everything in that book, it would give me a good start. I still to this day use a lot of what I learned in that book.

So you went to school and read books and got a job as an assistant?

I got a job at Smoketree Studios as engineer/assistant/whatever. After that, I worked at a studio called Redondo Pacific, and after I left there, El Dorado hired me because they’d just purchased an MCI automated console, which I knew how to run.

That was the first El Dorado—it’s now torn down—a studio built in the ’60s for rock n roll. Of course, this was the late ’70s and it was still in the ’60s. I went in there and the owner gave me $4,000 to redo the whole studio. So I hired an acoustician for one hour for $160 and had him write down on a napkin what he would do if he was going to remodel. Then I hired a foreman, brought in a crew and redid the control room. And that was the room where I did “Rockit” and Talking Heads.

That’s where I really learned, because I was by myself—I did everything that came in the door and all the maintenance, too. Disco, country or rock ‘n’ roll, I approached it all the same. If I didn’t know how to do something, I’d get the book and read about it, or I’d make phone calls and pick people’s brains.

How did “Rockit” come about?

I’d already worked with David Byrne and Brian Eno, and Tony Meilandt, who worked for Herbie Hancock, came to the studio and said, ‘This will sound crazy, but if I put you with Herbie and this production team called Material, I know we’ll get a Gold record.”

Bill Laswell and Michael Beinhorn were the two Brooklyn guys who were Material. They had recorded the tracks, then they came out here and we did overdubs in Herbie’s garage and mixed it in a couple of days. The record company people came to the studio for the playback, and when it was over they just sat there…stunned. Because there was this new thing called sampling on it, and scratching. And no singing. They were like, “We’ve got to have vocals, let’s put some vocals on it!” Bill Laswell was sitting there with a beer in his hand and he laughed and said, “I’ve got a plane to catch.”

About three months later, I was in Manhattan and I saw a kid on the street with a beat box dancing to “Rockit.” People were throwing money into a jar in front of him and I thought, “My God, I’ve just recorded something big.”

You met Herbie because you’d worked with Eno and Byrne. How did you meet them?

After we’d redone El Dorado, we were going to run an ad in Mix magazine. I looked at our pitiful equipment list—people back then were using nice live chambers and EMT 140s, and our reverb unit was a BX10, a little cheap, dark, spring reverb. I couldn’t advertise that, so I made up something. I said we had a new digital thing called a Lexicon 224. My plan was to go to the owner if we got any bites and say we had to go out and buy it. I’d done this before—he always came through when he saw a need for something that we’d actually make money on.

About a week after Mix came out, Brian Eno called—he’d read about the 224 and wanted to look at it. In a panic, I called an equipment broker who had one that was going to The Village Recorder. It was the only one in town, and everybody was screaming to get their hands on it, but I begged him to let me borrow it and he did.

Luckily it was easy to use.

I learned it literally an hour before Eno got there. He walked in, and I acted like I knew all about it. How he listened to it was by using some cassettes of beats that he was working on—we scrolled through the different sounds and I said, “These tracks are really cool.” Brian said, “You like this stuff?” and we started talking about music and then he left. A few days later the studio manager said, “You must have made a great impression on Brian Eno; he just booked nine weeks with David Byrne.” And out of that I went to the Bahamas and did Remain in Light

Somebody told me once, “If you can picture yourself doing something, you can get there.”

Well, for me, it’s the same with equipment: If I imagine myself using the piece of equipment I want, somehow it arrives in my life. The latest thing my engineer Brian Carlstrom and I were imagining was a full digital studio, and now we’ve got 48 tracks of 24-bit Pro Tools.

You’ve thought about a digital studio for a long time.

I’ve always been interested in the idea of hard disk recording—the problem was reliability. The Pro Tools sounds great, and I like all the plug-ins. We haven’t had any problems—no system crashes, no loss of information. The biggest problem, I think, even for those with experience, is it leads you to a lot of choices; you can get lost in it. We’re good at avoiding that problem. Brian [Carlstrom] and my assistant, Annette Cisneros, and I have done a lot of records together. So we approach our recordings the same as always. We don’t get lost in the process, and instead of adapting to the Pro Tools method, we have the Pro Tools method adapt to us.

Do you record directly to Pro Tools?

We do on overdubs. We start off on the Studer for tracking, and I mix to the Studer half-inch.

I’m surprised that you record guitars directly to Pro Tools.

Some of them we do, some go to analog. There’s so much opinion about digital and analog, and through the years I’ve been involved, on the sidelines or actively, in all these different arguments about equipment: about VCAs not being any good, Neve vs. SSL, blah blah blah. My whole philosophy has always been to use what gets the job done the best.

I’ve mixed stuff that’s been done on really cheap equipment that sounds gorgeous, and I’ve worked on a lot of stuff that’s been done on all the proper high-end gear and it sounds like crap. It’s all in how you record it. Because most people don’t know what a good sound is, they just go fishing.

I’ve always heard that if you replaced a sound, you were quick to get rid of the Original

[Laughs] It’s not that I have to erase stuff to keep my psychological center; it’s just practicality. Sometimes I’d do that only because I didn’t have the opportunity to save stuff, because I didn’t work in studios where I could make slave after slave. But I don’t see any point in holding on to something if I know what I’m going with. I don’t always erase everything, but I have absolutely no problem making decisions.

When I first started out, I had a 24-track machine and a 28-in board, so all my recording had to be very organized, and I had to print all my effects. When I shoved up my faders for mixing, it was pretty much just balancing, and we were done. I still print any important effect. I’m economical, and I don’t leave choices for later.

The studio here seems very live—is that where you like to put the drums?

Actually, I usually put the drums in the smaller iso booth, then I put a P.A. system out in the studio and pump the drums back out through that. It’s a way to control the amount of cymbals, because when you set up in a live room, you often get too much of them. I also control how much cymbals I get by how far I open the sliding door between the booth and the room. That way I can vary the sound and tailor it for each song, instead of having the same drum sound for the whole album.

I also use Ibanez DM1100s on the room sounds. I got turned onto them when I was doing Jane’s Addiction—Perry [Farrell] used one onstage for his vocal so he could adjust the delays and effects as he was singing. He lost the box, though, after the Nothing’s Shocking tour, and we couldn’t find another one. Then just a couple of years ago, I was in Black Market Music and I found two of them. The guy said, “You can have these pieces of junk for a hundred bucks each.” I’ve been using the hell out of them since, and one thing I use them on is drums.

It’s a chorus and delay.

It’s a delay unit. Within that, you can get chorus and phasing. See, the most important thing for me in recording is taking care of the fundamentals. The physics of sound are so simple, there aren’t really that many things that you can do with it. You can change the level, the amplitude, the phase, anywhere from zero to 360, and you can change the time, you can delay a sound. That’s it.

Everything you hear in the studio comes from those fundamentals. If you look at phase and use it to your advantage, being aware of how time can relate to phasing and being aware of amplitude, as far as the Fletcher Munsen curve—all that stuff—you can create the effects you want. You’ve got to be aware of the basics. For example, I use a sound pressure meter when I work.

That’s pretty rare in a recording studio.

Well, the optimal level for mixing is 84 dB. I have a mark here [on the monitor pot] where 84 dB is, but I still check it every once in a while.

Why optimal?

Remember, 84 dB on the Fletcher Munsen curve is the optimum between highs and lows, as the human ear hears them. When things get lower in volume, the bass tends to go away, so you’ll put too much in. At low volumes, you may also tend to put on too much high end. If you listen too low, when you turn it back up it may be too bassy and too bright. On the other hand, if you listen too loud, the stuff may come out bass and presence shy.

Those fundamentals are the most solid ground you can work on; I think people often overlook that now. They think in terms of, “This is recording.” But it isn’t—it’s sound. I also like to keep track in a mathematical way of all that stuff. I know what my delay times are from the earliest room sound, all the way up to a half-note, and the triplets.

Why?

I don’t use reverb much, so how I get a spacious sound if I want it (instead of just slapping on a reverb unit, which may just sound dark) is to use various delays.

Reverb is just reflections, coming from how far the walls are apart within a certain spatial environment. Digital reverbs use algorithms, which are mathematical templates that will simulate a room size with delays. What I do is to take the tempo and meter of the song and set up delays that correspond to those reflections—the earliest reflection in a room sound would be about 30 milliseconds, all the way up to a half note, and the triplets, and the dotted…I set up all these delay times for the tempo of the song. If the tempo changes, I recalculate.

Having the basics down frees you up to be creative.

It’s easier to learn a few basic rules than it is to try to learn every piece of equipment. You can spend your time learning how a Harmonizer 949 works, then some day you don’t have one and you want that sound. Well, think about what that 949 is doing. There’s so many different ways to solve a problem—you don’t need to have a 949 to have its sound.

If I was stuck on a desert island, I’d need something that could delay, and it could just be a tape machine. And I’d need something that you could change the phase with—that could be a soldering iron. So maybe a tape machine and a soldering iron is all I’d need.

When I set up mics, for doing drums, the first thing I’m always thinking about is phase—will one mic serve better than putting up four mics? I keep that in mind, thinking, one foot equals one millisecond. Sound travels at 1,100 feet per second at 70 degrees at sea level, and a millisecond is one-thousandth of a second, so, basically, one foot is one millisecond.

So you’re using the three-to-one rule to prevent phase cancellation.

There’s that, and there’s also the other one, the 9 dB one, where you can look at your console meters, and, if you have a mic on the snare, and it’s picking up a tom over here, the tom should be 9 dB down from the main snare signal so there’s no phase discrepancies.

Uh, do you own stock in Summit?

[Laughs] No, my engineer does. I like the sound of tubes. We use the preamps, compressors, EQ…line mixers, too; there’s a full studio in this rack. We mainly just use the console for monitoring and mixing. Even though I use the VCAs on the SSL to mix in the end, and I’m recording on Pro Tools, the first introduction from the outside world into the studio of every sound is always through tubes.

What are your favorite microphones?

Lately I’ve been using really cheap mics, like ones that come with phone machines, because there’s a color I’m going for. But I do like Telefunken 251s, U47s and C-12s. As for a desert island mic, probably the most versatile is an SM57, and for a good, balanced condenser mic, the U87, or my favorite, the U67.

What mics do you use on drums?

My setup for drums is pretty much the same all the time, and probably the same as anybody else’s. More important than the selection of the mics is the selection of the drums. I use The Drum Doctor, Ross Garfield, a lot; he’s got three snares I like. I mike the top and bottom of the snare with SM57s, with the phase flipped on the bottom. I like a fatter hi-hat sound, almost like a heavy metal hi-hat, so I go for those kind of cymbals, and on that I’ll use either a KM84 or a Sennheiser 451, with pads. I always top-and bottom-mike the toms, unless they’re concert toms, and I almost always use toms with top and bottom heads. I use Sennheiser 421s on the top and SM57s or 421s on the bottom, with the phase flipped on the bottom.

For overheads, C-12s or 87s or 414s, and I try to make sure the ride cymbal is picked up properly. Sometimes I have the mics over the drummer’s head with a stereo technique, or I’ll just have them spread out. Sometimes I’ll use various condenser mics, 84s or 451s, as filler mics to pick up China cymbals, or whatever else they may have.

For bass drum, I use an AKG D112; I put a sandbag in there, and usually I have a front head on with a hole cut in it. I like using smaller bass drums; they’ve got more punch—a 22-or an 18-inch kick sounds great to me. A 26 is good if you’ve got the right room for it and you want to go for a Bonham sound, but if I’m going for a sound like that, I use less mics and a lot of compression with Fairchild 670s, going for that classic “Andy Johns” drum sound. But usually I stick to smaller kick drums. And, of course, I compress everything when I’m recording.

How do you mike electric guitars?

A 57 angled in at 45 degrees, coming in somewhere between the center or the edge of the cone.

That’s quite a large road case your amp heads are in.

I prefer to have the amp heads in the room when I record. I had the cases designed by Anvil—we hook them all up, and I can go through them, boom, boom, boom, and see what we want to use.

Do you tri-amp the speakers?

What you mean. I think. is what I call triple tracking—I approach guitar sounds with highs, mids and lows. So, instead of bringing all three up with one sound, and one amp, using EQ, I’ll use an amp basically dedicated to lows, one delegated to midrange and one for high end. I might use a Vox, or a Matchless cabinet like an AC30 with a Big Muff, that will give a big bottom end, especially with a Les Paul. Then for midrange, I’ll use some kind of Marshall, a 50-or 100-watt lead, or a Bogner, and for high end I’ll use a Soldano or another Bogner for a more piercing sound. The basis of the sound is the Marshall in the middle, and I’ll bring the others into the mix. I don’t mix them onto one track; they stay on separate tracks all the time—for some reason, it just sounds better. I’ll use three amps for the bass, too, when I’m tracking.

To split the tracks, I use something called the Lucas Deceiver, which is a box that takes care of the ground problems. It’s an active splitter, with an op amp. Terry Manning builds them down in the Bahamas. I love the Deceiver. People ask me all the time how I split the signal; then they try to do it without one, and they give up because of all the ground buzzes and stuff.

Do you own a lot of outboard gear?

What I own is more musical stuff—amps, synths. I do own some EQs—Trident A range, a Neve Prism rack, Massenburg, API 550s—but the outboard tools I use are pretty simple.

When I mix, I have only a couple of things plugged in on the board: an H3000 Harmonizer, my AMS DDL and maybe a long delay—all the other effects have already been recorded. It’s not like some guys who have to have 100-input boards because they have all this stuff set up.

I understand setting up a bunch of equipment and just seeing what’s going to happen. I’ve done that, but in the mixing process there are already a lot of creative decisions to be made, so I believe that when you get to mixing, you’re not recording anymore, you’re not creating in that sense anymore—you’re creating in the sense of putting together the song.

What’s new on the market that impresses you?

Software. Acid, by Sonic Foundry, is very interesting. It puts together loops for you, one against the other, automatically. Pretty amazing. Unfortunately, it only runs on IBM, and our setup here is Mac—I have it loaded in my IBM notebook. I also really like AMP Farm. It emulates like 40 different amplifiers quite well. If I want a really authentic AC30 sound, I have AC3Os I will use. But AMP Farm does get a pretty good AC30 sound. It’s the guitar equivalent of drum samples.

Do you still spend a few days in the studio getting comfortable before you record?

When I’m recording a whole album, there’s a period where I’m trying to acclimate the band to the studio. I get them used to the headphones, the smell of the studio, what the coffee tastes like—it only takes a couple of days.

The point being, if you are going to do something important in the creative world, you have to look beyond just pushing around faders; there has to be a bond made between the producer, the band and the engineer. It’s almost like a family, and you have to understand each other and establish trust.

Also, recording should be fun, it shouldn’t be this arduous process of 18-hour days, seven-day weeks, to where you’ve totally lost perspective and you’re completely burned out. It should be fun, like going to play a baseball game.

Bill Szymzyck once said to me his philosophy in the studio is, “If you’re not having fun, it’s time to go home.”

I agree. I don’t have any problem going all night if everybody’s having a good time and it’s working, but how I generally schedule my work is six days a week, eight hours a day. Now that’s the hours I’m in the studio—the engineer will be here more hours, making backups, etc. But the eight hours I’m here are all focused work. I’ve got a goal for the day, and when I’m done with it, we go home.

I saw a quote from you in HiFi where you said your style as a producer is to do your job and to let everybody else do theirs. But you didn’t say what your job is.

When people ask me to produce a record, that means, to me, to make a record by whatever means. I may be a psychiatrist, a technician, a musician, but the overlying important thing is that I have a point of view all the time. The main job, which may include all those other duties on top of it, is to be a person who has a point of view and maintains it on the whole project. I let the musicians make the record and do their parts, but it’s in the framework of a point of view that we’ve all agreed on. Because productions can get lost really quickly if the objective has not been maintained.

To do this, I use my initial reactions as a listener, and I ask questions. What do I expect to hear from this person or this band? What is the essence of this band? That is, stripping away everything they’re not, and then looking at what’s left. We get in agreement, musically and stylistically, about what they are, and we form a general image of what it’s going to be, the theme. We fine-tune as we go along, but we’re always moving toward the objective, so at the end of the day we can say, ‘Yeah, we made the record we wanted to make.’ That’s the job.