PBS AIRS HD/5.1 SURROUND TRIBUTEWhen the Italian craftsman Bartolomeo Cristofori built three pianos in 1722 under the patronage of the Medici government, he couldn’t have predicted that one of them would be featured 278 years later in full-blown, High Definition (HD) and 5.1 surround sound on PBS. But one of Cristofori’s pianos – believed to be the oldest piano on Earth – survived long enough to participate in the instrument’s birthday celebration. That piano, on loan from an Italian museum and currently on display at the Smithsonian Institute as part of an exhibit marking the invention of the piano in 1700, is briefly spotlighted in “Piano Grand! A Smithsonian Celebration,” which aired on PBS in late November.

(At press time, it was uncertain if PBS’ November telecast would include the HD/5.1 version, as the network was still working on its capacity to broadcast in HD, but that version will be broadcast eventually and is available on DVD. In addition, NTSC/stereo versions were created for home video and shorter, pledge-break PBS broadcasts.)

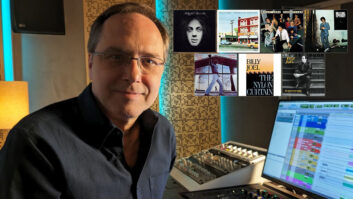

Produced by Smithsonian Productions, Maryland Public Television and Japan’s NHK and hosted by Billy Joel, the two-hour show featured concert-style performances by a star-studded lineup of pianists in most major genres: Billy Joel, Jerry Lee Lewis, Cyrus Chestnut, Robert Levin, Katia & Marielle Labeque, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Dave Brubeck and Hyung-ki Joo, to name a few. The broadcast also highlighted documentary-style segments about the history of the piano, anecdotes and backstage interviews with the participating musicians.

While Cristofori’s piano was obviously not playable, 18 other pianos did see action during the show, which was recorded before live audiences over the course of two days in March on a soundstage at the BET (Black Entertainment Television) studios in Washington, D.C.

To tape the piece, producers used an ambitious combination of 11 Sony HDC-700 and HDC-750 camcorders, which were rented from HD Vision of Dallas. Because PBS wanted to conform and eventually broadcast the show in HD and 5.1 surround sound, the producers faced a host of technical issues.

“The biggest creative challenge was the need to perform and record all the music in one location and do it in such a way that the paying audience would enjoy the performances,” says the show’s co-executive producer Wesley Horner of Smithsonian Productions. “We wanted to design an environment to take advantage of TV’s power for intimacy and stage it to appear like a live concert event, even though it was an in-studio production. It was a large studio, about 200 to 300 feet long and 80 feet wide, with an audience of over 300 people. We wanted something similar to the feel of PBS’ `Sessions at West 54th Street’ and let the television audience see the lighting instruments, cameras and mics. The real issue was that we had a Rubik’s Cube of pianos, and we had to match them with artists and figure out how to stage each performance.”

Horner brought in Steve Colby of N.H.’s Evening Audio Consultants to set up the P.A. system for the live audience, produce the audio recordings and perform initial mixes on the show’s 30 musical numbers. In pre-production, Horner and Colby worked with director Matthew Diamond to chart every music score scheduled to be in the show, choreographing camera angles on four specially designed stages in order to permit Diamond to switch live from a video production truck while taping performances. That painstaking pre-production work was crucial, because it allowed producers on the video and audio sides to streamline the amount of material needed to collect for the looming post phase.

MIC ISSUESTo record the performances, the producers hired Dave Hewitt and his company, Remote Recording Services of Lahaska, Pa. Using a Studer D827 48-track recorder in conjunction with a pair of Sony PCM-800 recorders (the Sony version of the Tascam DA-88), Hewitt and crew recorded the performances on 64 tracks of digital audio. The recording method, according to Colby, was capturing pristine piano recordings in stereo, along with separate ambient sounds, and in the post phase building them into a 5.1 mix.

In many ways, Colby says, that process was fairly straightforward, once a microphone plot was figured out for the 18 pianos and the BET facility. Eventually, a total of 96 microphones were used throughout the two-day shoot (counting voice-overs, interviews and orchestras), but Colby says the piano mic issue initially raised philosophical questions. He used fairly standard configurations for miking orchestras and interviews, but for the pianos and ambient surround elements, he needed a uniform approach to a diverse set of circumstances.

“There was a major philosophical question we had to answer in deciding how to mike everything,” explains Colby. “On the one hand, we wanted a consistent sound, even though we were recording very different pieces of music and musical styles. On the other hand, we wanted to reveal the character of each piano, and at the same time not have the mics get in the way of the picture or interfere with the live audience’s enjoyment. After much discussion, we decided to go with a single manufacturer for all piano mics – Schoeps.”

For the most part, each piano was miked with a Schoeps CCM 4 (a miniature cardioid Collette mic) and a Schoeps MK 21 with a cardioid capsule mounted on a Collette system.

“With pianos being sort of long, curving rectangles, we could hide the small mics,” he says. “On most of the pianos, we hid the first mic in the crotch, that swooping curve. The second one we positioned at the far end from the performer, at the tail piece, pointed back toward the keys. That gave us a warmer, easier sound for the second microphone position. With a couple exceptions, all the pianos were miked in the crotch and tail.”

The big exception was the rock `n’ roll piano used by Jerry Lee Lewis. “In that case, the rock piano is meant to be more aggressive, more percussive, with a harder-edge sound,” says Colby. “Putting the mic in the crooked tail area wouldn’t give us that kind of detail and aggression. We wanted to get the mic close to the hammers, to isolate it and just get the piano and not the surrounding electric guitars and things. The other problem is that the rock stage was constructed like a `T’ with the audience sitting on the bottom of the `T,’ and a grand piano on one side of the `T’ and a rhythm section on the other. In order for the cameras to tape the musician clearly, we had to make sure the mic didn’t block the view. So, we used Schoeps BLM (Boundary Layer Microphone) mics, which are specifically designed to pick up sound as it collects on hard surfaces. It used the piano lid as the integral boundary to collect the sound so we could let the artist play with the lid closed, with the mic on the edge of the piano.”

For surround elements, the Remote Recording Services’ team strung Audio- Technica 4041 mics throughout the room, collecting enough general material, according to Colby, to build a 5.1 mix later.

“Producers wanted 5.1 surround, but, of course, the show was designed with different performers playing in different parts of the facility, so we couldn’t mike the entire place for complete surround sound,” he says. “Instead, we filled up eight tracks with room mics placed throughout the area, and as we mixed later, we picked through those elements and chose sounds appropriate to the area we were working with at the time. There was a bit of trial-and-error in doing it that way, but it was the only practical way to do it, given our logistics.”

MIX ISSUESColby says producers determined early on that, although the project would be conformed in 5.1 surround sound, “this wasn’t going to be any sort of phonic surround spectacular. It was more a question of enhancing, tickling the rear surround speakers, to give viewers the perspective of sitting in the space and being part of the live audience, not necessarily being literally surrounded.”

Therefore, going into the mix, both philosophical and logistical considerations determined the approach. The producers brought the entire post-production job – both audio and video – to Henninger Digital Audio and Video, Arlington, Va. There, Colby personally handled the music mixes before laying off the stems to DA-88 tape. Henninger’s David Hurley, the show’s audio editor, assisted Colby and then took over the show to perform the final surround mix, combining the music stems with interviews, documentary elements and ambient sound.

Because Colby had never before used Henninger’s AMS Neve Logic 2, 96-input, 24-fader board (connected to the digital recorders via MADI card), Hurley set up what he calls a “generic configuration” for him. This allowed Colby to mix 30 songs in three days without having to worry about learning the nuances of a new console.

In mixing surround stems, Colby purposely avoided the center channel, leaving it for Hurley to use for ambient sound, applause and interview/documentary audio. In that sense, he entered into the ongoing surround debate over the musical usefulness of the center channel.

“We wanted a specific style and uniformity to these recordings, so we didn’t want the home user to be able to tamper with the center and subwoofer and alter the result of the mix,” says Colby. “So we decided to live with the home frequency information in the two front channels. There was nothing earth-shaking going on in terms of surround, anyway, so our desire was to keep it simple. Some people would say that is not true surround. In the debate over whether music belongs in that channel, a lot of people feel it should be reserved for dead mono information and dialog, while others think lead vocals could go there. We decided to leave that channel for the announcer, documentary and ambient stuff. That also played to the creative style of the piece: The idea that this wasn’t just a concert show, but also a show with a documentary flavor, cutting back-and-forth to musical moments. We felt that made the transitions more dramatic to blossom out of the stereo field into the surround field.”

When the music stems were complete, Colby eventually had to leave the project to fulfill a previous commitment, so Hurley stepped in to perform the final mix. That step, he says, was performed by using the Logic 2 in conjunction with a 24-track AudioFile digital editor.

“We had hard disk recorders, but there was simply too much material and too little time to deliver to digitize all of it, so we mixed straight off the tapes,” says Hurley. “I played an assistant role to Steve while he took care of the songs, and then he would lay off 6-channel stems for me. From the EDL provided by the HD room, I autoconformed portions and manually conformed other portions until the show came together, placing the performances in the right sections in conjunction with the nonmusical material, and then making music edits as needed, cutting it all together with the Billy Joel standups. Most of the edits were based on decisions made in advance by the offline video editor, so much of it was fairly standard. I did go back to original sources for some of the transitions – the end of one song and the beginning of a different one. I might steal applause from one end and put it onto the start of another song, and so on. With a show of this length, on this deadline, there were lots of transitions that were not pre-assembled in usable form, so I had to do a lot of that by ear, using a combination of Steve’s mixes and other material from source tapes. For the final permutation of the show, I took Steve’s sort of quad mixes, and by adding dialog and ambient sounds and such to the center channel, I made it into more of a true 5.1.”

DOLBY E ISSUESAs the project progressed, the Henninger team found itself faced with a major engineering problem. PBS insisted the show be delivered in the Dolby E audio-coding format, designed specifically to ease future post-production as the network produced different versions of the show in different audio formats.

Brad Hughes, Henninger chief engineer and the man in charge of solving all technical issues between the show’s video and audio worlds, says the PBS request made sense because Dolby E would allow the network to transfer, synchronize, encode and broadcast the show to HD-ready consumers in the Dolby AC3 surround format. Dolby E would also allow the producers to easily develop a letterboxed version in ProLogic or stereo formats, without having to re-encode for each version.

Unfortunately, at the time the project came to Henninger, Dolby E and Sony’s HDW-500 playback recorder weren’t exactly the best of friends.

“It was a major problem for a while,” says Hughes. “PBS didn’t have Dolby E encoders at that point, so we needed to find one ourselves. I had our local Dolby dealer get us a prototype box, but we quickly found out we couldn’t do an encode to our HD-CAM machines [the HDW-500]. Before the project began, Sony told us we would need a model kit to modify the HDW-500 to talk to Dolby E, which they said would be no problem. But when we started the project, they said they had scrapped the plan to distribute the model kit, and instead, the new versions of the recorder would automatically convert to the format at the press of a button. Of course, that version wasn’t available to us yet, so it was a huge concern.”

Hughes solved the problem with tenacity – by “doinking around,” he says – eventually finding an HDW-F500 recorder compatible with Dolby E. “Basically, with the new HD 24P format coming up, we’ll need to replace all our earlier HD equipment anyway,” adds Hughes. “So, we would have gotten the box sooner or later, but this project was so far ahead of the curve technically, we couldn’t wait.”

Overall, Hughes says these and other issues would have been more complicated to solve had producers not decided to bring the entire post phase – audio and video – under one roof at Henninger, a facility located close to Smithsonian producers in Washington, D.C., and PBS producers in Maryland.

“Having the mix under the same roof as the online edit (performed in linear fashion in a Henninger online room using Sony high-def switchers), was a huge blessing,” he says. “There were so many versions of the show, for one thing, especially all those down-converted versions that did not have the surround mix, so there were lots of changes all the way through. Being the chief engineer, I could find the audio guys, ask questions about the mix and make sure everything matched with the video. That was real important during the Dolby E layback: We had everyone in one room who were required to make sure all the tracks ended up in the right places.”