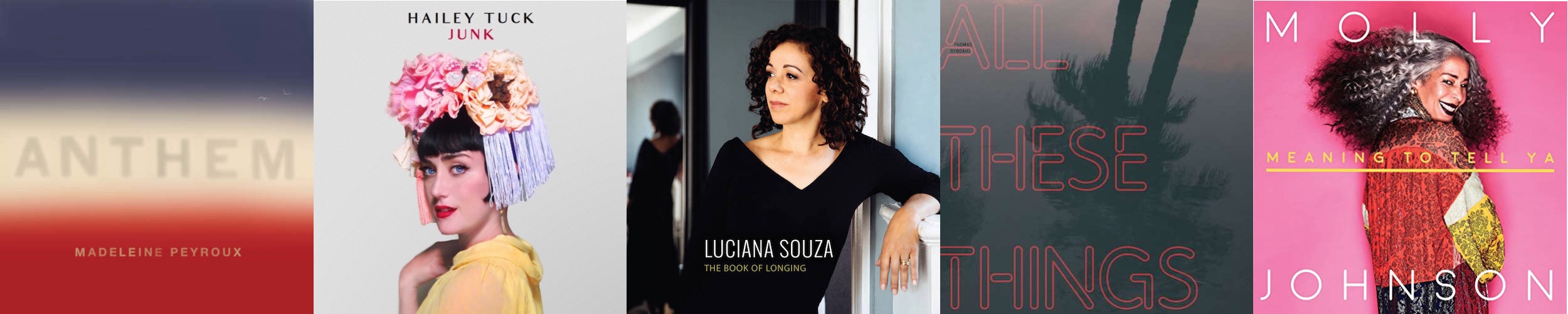

Larry Klein was up for Producer of the Year at last month’s Grammy Awards— for the third time. He didn’t win. Or the other two times. But it’s inconsequential. What really matters is the body of work. Just this past year, the albums on which he worked as producer were All These Things (Thomas Dybdahl), Anthem (Madeleine Peyroux), The Book Of Longing (Luciana Souza), Junk (Hailey Tuck), and Meaning To Tell Ya (Molly Johnson).

Not that he hasn’t been honored by NARAS. He’s received four other Grammy Awards for his iconic work, beginning in 1996 with Joni Mitchell’s Turbulent Indigo for Best Pop Album, followed by an award for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album for Mitchell’s masterpiece Both Sides Now in 2001. In 2008, Klein took Grammys for Album of the Year and Best Contemporary Jazz Album for Herbie Hancock’s River: The Joni Letters.

Klein started out playing bass with jazz artists Willie Bobo and Freddie Hubbard. It wasn’t long before he was an in-demand studio musician playing with the likes of Bob Dylan, Robbie Robertson, Tracy Chapman and Joni Mitchell, who quickly enlisted his musical expertise that led to his first co-production with her on Dog Eat Dog. Klein’s first solo production flight in the studio was on The Cars’ Benjamin Orr’s The Lace in 1988, followed quickly by Mitchell’s Chalk Mark in a Rainstorm.

Record producer, songwriter, collaborator, bass player, film scorer—it’s clear that music runs through Klein’s veins and he maintains an endless passion for both sides of the glass. This is a man who not just loves to work, but lives to work. Assuredly, it’s not about winning a Grammy; it’s about the music.

Of the four nominees for Producer of the Year this year—Linda Perry, Kanye West, Boi-IDA and Pharell—you were the senior member in an industry that is often guilty of ageism. How do you account for not only your relevance, but also your continued nomination for such awards?

For me, the biggest factor is curiosity. I’m a very restless creative person, and I’m always trying to do something new with each record I make. The driving wheel for me in making records is not to have a big hit record; it is to make something fresh and take elements of things from different areas musically and recombine them in a way that feels new. I do keep the pragmatic aspect of doing something that is going to appeal to a lot of people in the rear view mirror, but the driving force is to make something fresh. There are people who make records specifically to make a hit record, and that’s fine, but I think it’s somewhat of a shortsighted way of dealing with this job.

Joni [Mitchell] always has said the worst thing that can happen to you is to have a hit. It can box you into something and people will always expect that thing from you. And if you don’t love that thing you just made, you’re cursed, and it’s going to follow you forever and you’re going to have to make that thing over and over. If you make something you love and it turns out to be a hit, that’s fantastic. And if it doesn’t turn out to be a hit, you still win because you’ve made something you love and are proud of it and people will see the beauty in it if you do.

Many producers believe relevance is driven primarily by technology.

I utilize elements of the current technology, but I also utilize antiquated technology to get at things that make me feel something in music. The purpose of art is to make us feel something and to defeat the numbness that accrues from the day-to-day routine, or the terrible things in the world, or the insensitivity of people, or whatever things that grind us down and make us less sensitive to what we’re feeling. Music, at it’s best, like a great painting or a great film, cuts through all that and makes us feel something deeply, and that way we become more human.

Besides that goal, what else is important to you as a producer?

The first thing I do when I meet an artist is assess the element in them that makes me and others want to listen to what they’re doing. Then I start thinking about how I can enhance that. Sometimes that involves writing with the artist and helping them flesh out their writing, sometimes it involves taking a stronger hand in helping them arrange the songs, sometimes it involves how they’re approaching singing or playing an instrument, and sometimes it involves all of the above. One of the things I love about my job is that it is completely different from artist to artist.

Let’s talk about the artists you worked with last year, starting with Madeleine Peyroux.

From the time I first worked with Madeleine on Careless Love, in addition to being a great, natural singer, she always wanted to be a songwriter. My work with her has been a journey to help her toward being more active in her records as a songwriter. When it came to Anthem, I proposed we do a group write with a set of great musician writers who are like-minded souls. In the end, we did end up using one cover.

The title track, by the omnipresent artist in your life, Leonard Cohen.

Covering his songs with different artists keeps him around me, not only because of our friendship but because there are those special souls that exist in the world that are just supercharged that way. In my life, he’s certainly been one of the people I’ve learned the most from and that I laughed the hardest with. Walter Becker is another, and of course, Joni. Warren Zevon was another. I’ve been lucky to connect to these people who have been like my older brothers I never had, or teachers.

The muses in your life. And of course Leonard is on your wife, Luciana Souza’s, record, as well as Molly Johnson’s project.

That’s right. Molly is a real social activist, and like Madeleine was in a state of disease about what was going on in the world. We tried to find some interesting ways to express that in some of songs we did on her record. We did a Marvin Gaye song called “Inner City Blues,” which is more topical to what is going on now than ever. Then I don’t think anyone has ever covered Leonard’s song “Back on Boogie Street,” which is another one of those miracle songs that is beyond brilliant.

With respect to Luciana’s record, Leonard was a friend of ours, and when she became more aware of his poetry, it knocked her out, too, and lit her creative fire. On this project, she put four of his poems to music. Adam Cohen, his son who takes care of his estate, knew Leonard had let her put other poems to music, so he gave it the okay. So her project coalesced around those four pieces of Leonard’s and then she added an Emily Dickenson poem, an Edna St. Vincent Millay poem, a Christina Rossetti poem, and she wrote a couple of her own. It became a poetry project, which is perfect for her because poetry is a big part of her creative engine.

Tell us about working with Hailey Tuck.

She emanated from a rare, random thing where she got hold of me via email or social media, I can’t remember. I get a lot of correspondence from all over the world, and it’s very rare that someone writing me a message leads to my doing a record with them. But I listened to what she had done previously, and I thought, “This is very interesting.” I got back to her and she got on a plane.

She’s a very unusual and wonderful artist. I think of her as the Dorothy Parker of jazz. We got together and my manager got her a record deal, and we made this record that we thought of as driven by our mutual feeling that these times we’re going through right now feel a bit like we imagine what people felt during the Weimar Republic in the late ‘30s, with all that’s going on politically and all the xenophobic craziness that’s happening around the world.

Then Thomas Dybdahl also organically came about as sort of a portrait of the dark side of Los Angeles. I told him while we were making it that I thought of it as sort of a musical Day of the Locust. I’m a voracious reader and oftentimes I think of records I’m making in terms of literature.

A lot of darkness this year.

Yep. (laughs) No dearth of that.

What are the pros and cons of playing bass on a project?

It’s a decision I have to make on each project because I love playing, in any situation. But there are advantages to not playing, which are that I can solve musical problems or adjudicate takes on a song that we’re laying down or come up with arrangement ideas faster if I’m sitting in the control room listening.

But on the other hand, if I’m in the room playing with the musicians, that’s an equalizer. One of the things I like to encourage as a producer is the feeling that we are all just in this place trying to make some great music—not that I’m the producer dictating what to do. I don’t think you get the best out of musicians that way.

On Luciana’s record, that project arose from getting a certain amount of these pieces finished and her doing a little bit of touring with Scott Colley and Chico Pinheira. So they started developing a beautiful chemistry on the material. It didn’t make any sense for me to disrupt that. Plus, I love Scott Colley’s bass playing.

Your producing career developed from your work as a bass player with Joni. She trusted you very quickly from your first project with her, Wild Things Run Fast.

She brought in three songs to begin with and we did about a week of tracking dates. She enjoyed what was going on and went off to write some more songs, and a couple of months later, the phone rang and it was her calling about getting back together and doing some more recording. That stretched out over the better part of a year, and during that time we got to know each other musically and personally and I found her to be the extraordinary genius that she is. Eventually we started working closer and closer on the music, and things traversed over on the personal realm.

I read an interview where you said you made plenty of mistakes early on. Like what?

I came into producing records thinking it was a matter of troubleshooting, problem solving, coming up with arrangement ideas and design for musical architecture. As I made my way initially into the job, I wasn’t conscious of the importance of spirit in the studio. I think a lot of the mistakes I made were hearing things that were problems in a track and just blurting out what I thought were the solutions, and that’s only a small part of what a producer should bring to the table. A big part of your job is to elevate the spirit of the players and artist where they’re going to give you the best of themselves. Early on, she really nailed me on that and said, “What’re you doing saying these kinds of things?” And she was right. The work that we did together really shaped the way that I work now.

You recorded the album Both Sides Now in 2000, many projects ago, and it’s considered a masterpiece. But since we are often our own worst critics, I’m wondering, listening back today, if there’s anything you would change?

No. It just worked. We came up with this idea of making a record that used standards to delineate the arc of a relationship, from the initial flirtation to all the things that happen in a relationship, to it dissolving, but also to there being a good resolution to the relationship. We kind of based it on our relationship and marriage, and in doing so, I really felt we should do a couple of her songs. So we inserted “A Case of You” at the middle point and “Both Sides Now” as the song that defined resolution, in an unresolved way.

It amazes me that you and Joni were able to continue to work together during your split and after your divorce. I can’t imagine trying to keep the creative and personal relationship separate in the studio.

The pact we made from the very beginning of our relationship was that nothing was off limits to write about for the making of art. That was the case with her anyhow because a great deal of her previous work was centered around the search for love and the search for how to deal with the dilemma of making love last and the flirtation and the energy of new love, and how it has to metamorphose to the longer term thing that isn’t as charged.

The songs on Turbulent Indigo were explicitly programmatic of what was going on in our lives at that time. And also the songs on the previous records like Night Ride Home and Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm. There are parts on all those records that have to do with what was going on between us. It just seemed natural that that would happen.

That had to be difficult sometimes.

It’s difficult, but in the end it’s worth it. I’m now married to a singer/musician/songwriter/poet.

And you’re a glutton for punishment (laugh).

Maybe. (laughs) I’m consumed with music and art, so unless someone functions with that engine, there’s not a lot there.

It’s amazing, though, that you were able to create Turbulent Indigo in the midst of the break-up with Joni.

That was the pearl that came out of a lot of angst and difficulty.

And then to be nominated and win Album of the Year.

It was a complete long shot that we won. There were some extremely commercially successful records that we were up against that year, and we were both shocked that we won. It was wonderful.

And then we went to the Grammys that year with our respective boyfriend and girlfriend. The way we handled the whole process by still working together on records and still maintaining a friendship was kind of a bold experiment. There was an undercurrent certainly of tension (at the Grammys), but we got through it.

What’s the greatest lesson you’ve learned in the studio?

You have to be ready to sacrifice anything, including your best idea where you’ve already gone through congratulating yourself on cracking the code of the universe. You’ve worked for three days on this specific problem in the arrangement and you’ve found the miracle, but you have to be ready to toss it if it doesn’t make you feel something.

Another thing is, you don’t get any points for being just correct. You get all the points for making something that will resonate with people so strongly that it makes then stop and look at themselves, or the world, in a different way. You get no points for being correct or polite.

And what is on the slate for this year?

I just finished a collection of Jacques Brel songs and always was a Jacques Brel fan, but it deepened my admiration for his work. I am starting a record with a woman named Kandace Springs that Don Was asked me to do for Blue Note, another record with Melody Gardot, and I’m about to embark on producing a record for these people who are creating a musical about the Grateful Dead. I’ve never done a Broadway soundtrack record, so that should be fun.

Back to full-circle. You continue to stay so busy.

I feel very fortunate. Music is the lens through which I look at the world. I would be doing it no matter what.