“Serendipity,” John Storyk says soon after it’s established that we’re recording. “Maybe we could get the art director to watermark that word and run it across all the pages of the article. That’s the one word that sums up my life. I’ve said that for a long time. Might be kind of cool. I’m sure it can be done in print.”

Hmmmm. He’s an architect, so he thinks visually. And the art director might go along…

“And Beth. We have to talk about Beth,” he interjects, referring to his wife of 31 years, interior designer and textiles/fabrics sommelier Beth Walters. “There is Life BB and there’s Life AB—Before Beth, and After Beth. I mean that quite sincerely. None of this would have happened without her. And again, serendipity. We were both invited to the same Thanksgiving dinner back in 1985, and we haven’t been apart since.”

Of course we’ll talk about Beth. It’s the Walters-Storyk Design Group. She’s going to be on the cover with you…

“And we can talk about Jimi, too,” he adds. “I’ve told the story a hundred times, and it never gets old. . Talk about serendipity. I was 22 years old. I was an architect just starting out, by myself, living in New York City. It’s 1969. There was no grand plan. Then I get this phone call from Hendrix’s Manager, Mike Jeffery, and he tells me that Jimi would like me to design a nightclub for him. I’ve always said that it helps if your first client is a major rock star.”

And away we go. Let the three-hour Zoom session begin…

From Electric Lady to WSDG

It’s hard to overstate the impact that Electric Lady Studios had on the recording industry when it opened on West 8th Street in August 1970. Storyk didn’t invent the modern studio; not by any means. A&R and MediaSound reigned in New York. Record Plant New York and L.A. emerged at about the same time. Tom Hidley was being noticed. Bill Putnam had built some amazing rooms. Later came Vincent Van Haaff in 1970s Los Angeles. Still, nothing quite epitomized studio life at the time like Electric Lady, with it’s blend of style, comfort and technology. And it was owned by a rock star.

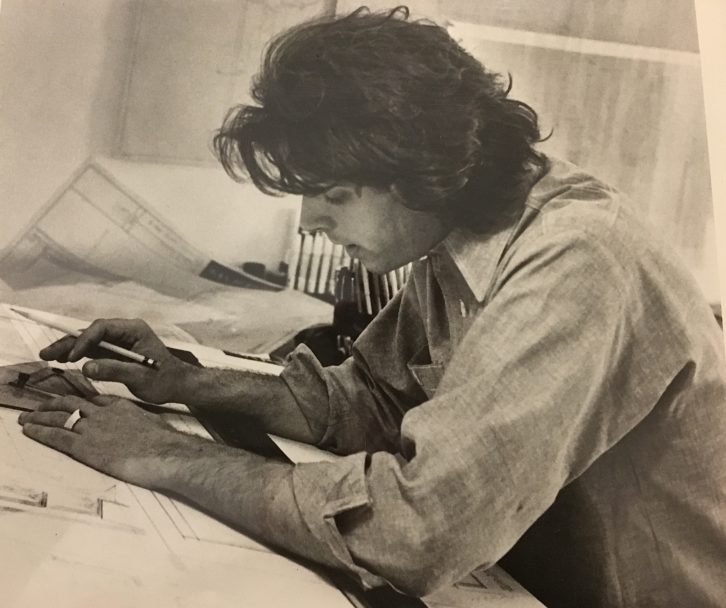

Still, it was supposed to be a nightclub. According to Eddie Kramer, Hendrix’s producer and engineer, Jimi liked to take breaks in the middle of all-night sessions and go out. One of his favorite clubs in late summer 1969 was called Cerebrum, down in SoHo, featuring an all-white interior, curved lines and a multi-colored lighting scheme. For nine months it was the hip place to go; it made the cover of Life magazine; and it was designed by a 22-year-old architect, recently graduated from Princeton, named John Storyk.

Jimi wanted a club. He bought The Generation, the hot blues club in town located at 52 West 8th Street, a club Storyk (a keyboardist and sax player) had frequented since his college days.. Jimi had his manager call Storyk, and a couple weeks later he delivered initial plans. Then Eddie Kramer stepped in and, according to legend, said, “Jimi, you spent $300,000 last year on recording. You don’t need a nightclub, you need a studio.” And just like that, while working days at an architecture firm and nights trying to make a go as a blues musician, Storyk’s first real solo commission was canceled.

“I didn’t even know him at the time, but I wanted to strangle Eddie Kramer,” Storyk says with a laugh, noting that Kramer was best man at his wedding and is godfather to his oldest daughter, Nadine. “But then they turned to me and said, ‘Well, you know, you could just stay on and do the studio.’ I said, ‘Guys, I’ve never been in a studio. I don’t really know anything about recording studios.’ They said, ‘That’s okay. You can read up on it. You’ll figure it out.’”

He did figure it out, along the way enlisting the help of Bob Hanson, an isolation expert, and Phil Ramone, then the owner of A&R Recording, among many others. By the time Electric Lady opened in August 1970, Storyk had three more commissions, one from a blues hero named Leon Russell out of Tulsa, Oklahoma. “I was a blues fan in the middle of building Electric Lady, but I wasn’t a giant Jimi Hendrix fan back then. When Leon Russell called, that to me was ‘the moment’.”

Still, he didn’t consider himself a studio designer. In 1971-72, he traveled through Canada with his then wife, eventually ending up in Boulder, Colorado, for a year while still working on studios back in New York. But that all ended, and he moved back to New York, entering studio design full time, including work in conjunction with Tom Hidley on a room at Record Plant for Stevie Wonder, set up by his friends Bob Margouleff and Chris Stone. He built it with audio engineer Bob Skye, who remains a close friend and a part of the company to this day.

He started his long association with Howard Schwartz Recording then, which would grow to 26 rooms. But it wasn’t until 1974 and the beginnings of his association with Albert Grossman (who he’d first met in 1969 while designing the original Bearsville Studios) that Storyk finally figured that he could make a career of this studio design thing.

“I had just finished additional work on Bearsville Studios up in Woodstock, and Albert essentially adopted me,” Storyk recalls. “He gave me a room in his Manhattan office on Fifty Fifth Street.. And, he allowed me to live on his property in Woodstock; I ended up living there for 15 years until he died. There was a little three-unit apartment building and he gave me one of them. I would be in the City for the week, and Woodstock on weekends.”

“Albert and I collaborated on the next Bearsville Studios, too,” he continues. “And the theater, Todd Rundgren’s video studio all the restaurants, a hotel for Albert in Oaxaca, Mexico, I even designed a house for him in Coral Gables. Albert was a huge builder. He became a mentor, a sponsor of mine in a truly Renaissance fashion. And Woodstock became my second home.”

By then Storyk had a small staff in Manhattan, spent his weekends in Woodstock and lived something of a rock and roll life. He built lots of studios, started to dabble in teaching, made a bit of money but still didn’t pay much attention to the fact that his career was also business. He started to bring glass and natural light to his designs. He had embraced CAD. Life was good. New York City in the go-go ‘80s.

“All these things were happening in my life,” he says. “And I had no idea that Beth Walters was looming on the horizon.”

Act Two: Family and Business

To Storyk, meeting his life partner proved the ultimate serendipity. “We were both invited to the same Thanksgiving Day dinner, back in 1985. She was a single mom with a six-month-old boy, I was sort of the date of the daughter of the person who was holding the dinner. , But by the end of the evening, I like to say, Beth was my girlfriend, though I wasn’t quite sure I was her boyfriend yet.. By the end of January, we were partners in everything.”

Walters, an interior designer with an affinity for fabrics and textiles, can strap on a tool belt with the best of them. She has worked in set design and fabrication, fashion and theater. Within three months of their meeting, they consolidated apartments, cars, second homes and offices. Over the next five years. Walters oversaw the continual expansion of their upstate home and property in Highland, including a softball diamond, a pond, a swimming pool and the construction of an outbuilding that became the main offices for the new Walters-Storyk Design Group.

“Beth brought color to the company,” Storyk says, matter of factly. “If you look at my body of work, you can see when I switched from mostly wood tones and blacks and grays—everything that Howie Schwartz ever built was black! And then you can all of a sudden see my work changing. And that’s Beth. She became the colorist and I turned more to the geometries, which was always my first love and still is to this day.”

Walters also helped establish a more hardcore business sense. “At this time, we had Nancy Flannery in the office doing the books and running operations,” Storyk says. We have two guys in New York and we’re making a little more money. But Beth turns to me one day and says, ‘We’re not organized and we don’t know anything about business. I’m a textile designer. You’re a musician-cum-architect. We barely know how to balance a checkbook.’”

So in the midst of transitioning upstate, Storyk called his longtime friend Chris Stone, co-founder of Record Plant and a shrewd businessman to come up as a consultant and check out their operation for three days, look at their books, then tell them what they should do.

“First thing he says is that we need an organizational chart,” Storyk recalls. “I said, ‘Chris, we only have five people.’ He said it doesn’t matter. You just need to know who’s doing what. Who’s reporting to what for what tasks. That had never occurred to me. Then he says we have to have an office meeting every week. And to this day, we have an office meeting every Monday at 9:30, every single Monday to this day. And third, he said, we have to abandon cash accounting and go into accrual accounting. Those three simple things changed our business, and I had never heard of the word ‘accrual’ before that meeting.”

The business would change even more dramatically over the next decade and a half, becoming truly global with the addition of offices in four countries and representation in a handful more. None of it was planned, not even the choice of countries. Global expansion, oddly enough, came about through the development of an internship program, which came about because of Storyk’s lifelong love of teaching, beginning at Full Sail back in the late 1980s.

“It started with a question from a student, who asked, ‘Do you ever have anybody work for you?’” Storyk recalls. “It’s as simple as that. We eventually created this three-month program, and now it’s extremely organized and we have applications and tests and everything. We house them; we pay them. Sometimes they become employees.

“One of our first interns was Dirk Noy, a Full Sail student,” he continues. “And within a week of being in the office, it was obvious that he was brilliant.

He was already ahead of me as far as sheer acoustic theory. And he could draw. I wanted to hire him when the internship is done. He wanted to, but said that he needed to go back to Switzerland. I said, ‘Okay, why don’t you go back to Switzerland and you can represent us. Open up a little office. We’ll front the money. Basel, Switzerland? I’d never even heard of the place.

For the first few years, he basically tried to get jobs. He got a few. Then he hired a second person. We formed a company after two years, and we now have eight full time people. And Dirk is now a 10 percent owner of our New York company. So the internships became employees, became representatives, became affiliates, became partners.

“It’s the same story with Renato Cipriano from Brazil, who came a semester later. He’s brilliant, and he’s also a two-time Latin Grammy Award-winning mixing engineer who can draw! Same for Sergio Molho in Argentina, who has since moved to Miami and is now co-COO with Nancy Flannery. Our first project down there was for Fito Paez years ago, and now Sergio is a WSDG owner too. They’ve all become family.”

John Storyk is a family man. Though his own family wasn’t particularly close-knit during his childhood, he holds tremendous respect for his father and mother, learning from them the importance of loyalty and commitment. He speaks with the pride of a father when he rattles of the list of people who have worked with him 20, 30, 40 years.

When he and Walters were approached by a large Midwest company about five or six years ago and asked if they would consider selling, they took the meetings. After all, retirement was coming. By the end of the process, Storyk couldn’t do it. He didn’t consider that a legacy. Instead, he and Walters came up with a five-year plan to lend money to Molho, Cipriano, Noy, Flannery and Morris, allowing them to buy into the company essentially through profits and a great deal of work. Those five years just ended. John and Beth now own 40 percent of the company; the employees own the rest. As John says, “What a way to end the first 50 years and start the next.”

Those financial moves are completely in character. John Storyk knows how much his career has meant to the shape of the modern studio, from Electric Lady to Jungle City Studios, and he maintains a bit of New York swagger to this day, but he tends to defer to (and remember) his friends and colleagues, like Albert Grossman, Ham Brosious, Bob Wolsch, Howard Sherman, Howie Schwartz, Marcy Ramos and so many others. At this point in his career, semi-retired but not really, he and his WSDG family have designed more than 3000 studios and production spaces. He’s the first to say that he had a lot of help from his extended family.

One of John Storyk’s favorite aphorisms is “Studio design is the nexus of architecture, acoustics and technology.” Now that he’s completed the First 50 Years of his remarkable career, he might want to tack on an amendment: “…with a dash of serendipity.”