Linda Ronstadt plunged a dagger through my heart when she told me that she hated her vocal on “Long Long Time.” I had been among the hordes of young girls to secretly sit in my room learning that torch song on guitar, desperately attempting to sing like her. And now to find out she didn’t like how she sounded!

But I did commend her on her straightforwardness, a quality I appreciated throughout our conversation. She laughed and said it was a product of being Dutch on her mother’s side and Northern Mexican on her father’s.

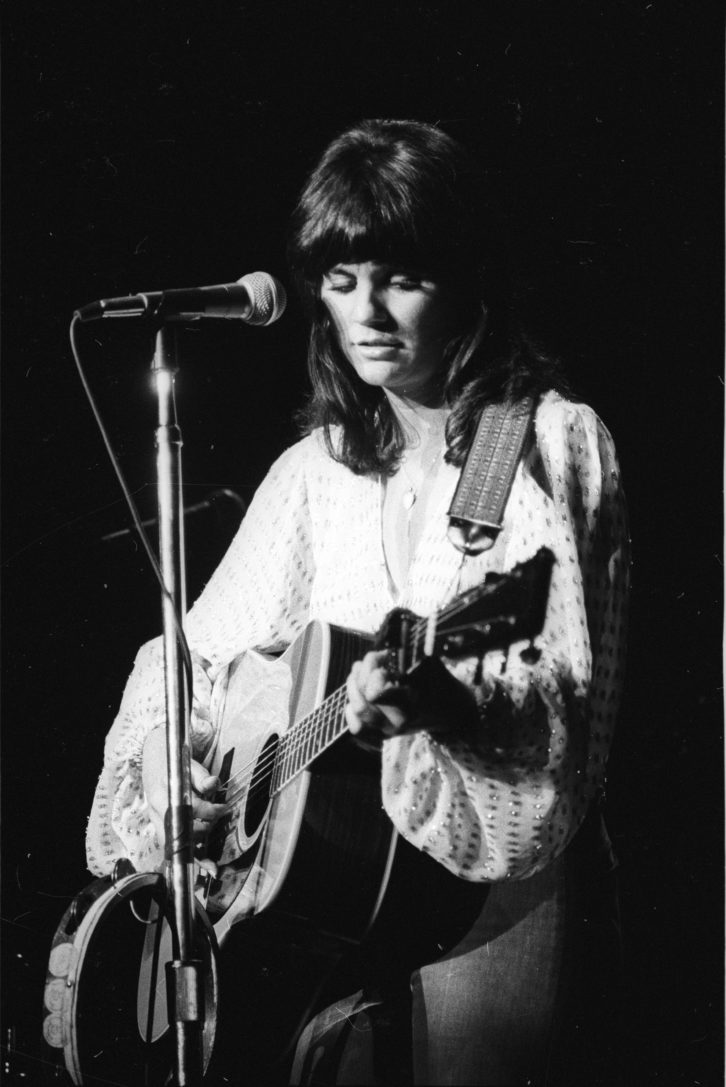

Ronstadt was born in Tucson, Arizona, and because her father sang folk songs in his native language, she began to sing them as a little girl. Her mother played piano and introduced her to the standards and Gilbert and Sullivan, the young Ronstadt singing alongside. She never had a vocal lesson until 1980, when she performed on Broadway in Pirates of Penzance.

At 18 she followed local musician Bobby Kimmel to Los Angeles to pursue her dreams. Not long after, they formed The Stone Poneys with Kimmel’s friend Kenny Edwards, and the trio made three albums within 15 months. Their second album contained “Different Drum,” which made it to Number 13 on the charts.

But the record company had different ideas and wanted her on her own. As a solo artist, Ronstadt had 14 platinum albums, and she went on to win 10 Grammy Awards and one Lifetime Grammy. In 2014, she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, as well as awarded the Presidential Medal of Arts. In 2019 she was a Kennedy Center honoree.

While considered the most successful female artist of the 1970s, by the early ’80s Ronstadt had tired of rock and roll and began to pursue new directions. She credits record company head Joe Smith with giving her the opportunity to make what he thought were career-ending projects, such as her American Songbook records with Nelson Riddle and her Mexican music records.

In 2011 she announced her retirement. Shortly thereafter, she announced that she was suffering from progressive supranuclear palsy, a condition making it impossible for her to sing.

Mix: Let’s jump right into it. After The Stone Poneys split up, were you scared to be on your own?

Ronstadt: I didn’t have any material. I knew a lot of country songs, which is why I ended up singing them, and I could play them on the guitar. I had to put a band together so they could play Stone Poney songs without the people who made them. Most of those songs were Bobby Kimmel songs, where I sang lead and he sang harmony.

I got some old friend from Tucson that I knew in high school to be in the band. It was not very well put together. There was a network of folk clubs, and you could earn a living while you learned how to play. We weren’t very good, and it was very humbling.

It was a different time. At the Troubadour there were two places—at the bar and the performance space—that complemented each other, and the gate was kind of fluid going back and forth between them. We learned a lot from each other then. It was only when we got to the big venues that we stopped learning from each other.

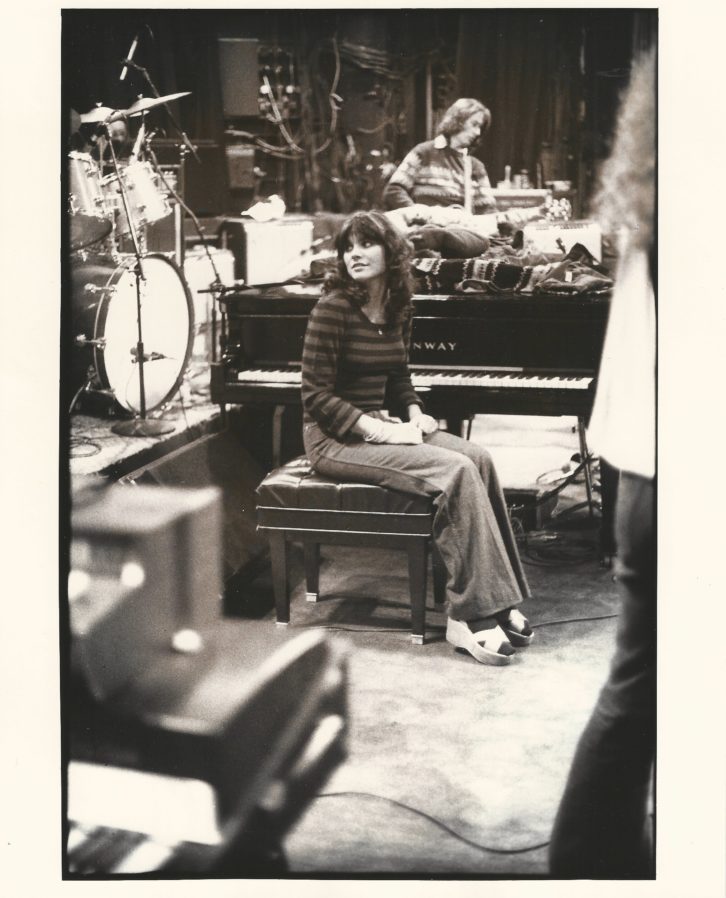

I noticed that on some of the clips in The Sound of My Voice, the CNN documentary about you, it appeared you were singing live in the studio with the band.

I didn’t start overdubbing vocals until maybe Get Closer. Peter Asher didn’t like to overdub vocals, and there wasn’t time to do it when I was at Capitol with Nick Venet. You went in for a three-hour session and you came out with three songs. The What’s New sessions I couldn’t overdub because there was so much stretching of time with the orchestra.

I had never sung “What’s New” in my own key before; I had only practiced it with Frank Sinatra singing it in a different key. I knew the song and most of the changes, but I never sang it with the arrangement that Nelson [Riddle] had written because I had never heard it before. It’s so expensive with an orchestra; you have to work fast, so three takes of it and I think we took the first one, so it was literally the first time I had sung that song in that key. I hear those records and I think, “God, I learned so much after I did them onstage. They would have sounded so much better if I had had the chance to sing them for a while.”

What was your biggest challenge in the studio?

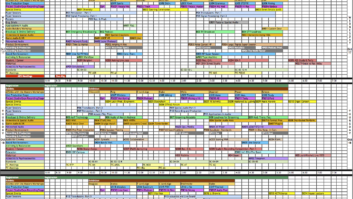

Not having enough tracks. [Laughs.] Keeping track, because I didn’t know when to stop, because I did a lot of layering—like my voice five times and a layer of brass instruments under that, and maybe a viola under that.

How much were you involved in the arrangement?

I was very involved. On “When Will I Be Loved,” I remember singing Andrew Gold the rhythm guitar parts in the bridge and I asked him to twin the solo, to play harmony to his solo.

So you often had the vision?

I worked the songs out as well as I could on guitar to know how they should be, and then we would try to get the right set of players to pick up the ball and carry it over the finish line.

Would you tell the producers which musicians you wanted on which tracks?

We would decide the right players. Mostly it was my band doing those early records with Peter—Andrew (Gold) and Kenny (Edwards). They got points on the records.

That was pretty unusual.

Jackson Browne and I were both doing it then.

With all that involvement in the music making, it begs the question, why weren’t you listed as co-producer until 1993?

I don’t know. I didn’t need to take it. I didn’t really need to take it in 1993. It’s just that I did so much of the work. George Massenburg has been such a great inspiration and teacher to both me and Peter. His method for overdubbing vocals is so incredibly good and he is so adept at it. Sometimes I’d just sing it all the way through and I’d be done, and other times I’d do a first, second and third take, and sometimes I’d sing five tracks. How do you keep track of five different vocal tracks in my head? I’d have to write it down and remember the one syllable from track three would match another syllable from track five. And then switch to track two for the next three beats and make a little vocal map.

What did George teach you?

He knew that technique, and he had invented some of the machines that actually supported you.

What did you need from a producer? You really didn’t have a lot of producers—just a few that you really liked.

Two I really liked were Peter Asher and Steve Buckingham, who produced the very last record I made, Adieu False Heart, which was a duet record with Ann Savoy. We called ourselves the Zozo Sisters. I didn’t have any voice left; I was singing on fumes then, but it’s one of my best records. Steve really understood me. First of all, Steve is a good musician and he knows all the players who play traditional music. I know a lot of them, too.

George produced the Trio records. We [Ronstadt, Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris] chose the songs and players and did the arrangements. We had natural vocal harmonies, but if we got stuck, I arranged the vocal harmonies.

Dolly said you were a slave driver.

Yeah, ha! [Laughs.] Well, it needs to be the right part and it needs to be in tune. Dolly has very good pitch.

All three of us worked out the arrangements with the musicians. What George did was make sure it was an absolutely natural sound. He’s really good at recording acoustic instruments and making them sound natural and keeping things moving. He’s great at spotting an interesting idea that comes up on the floor from one of the musicians and keeping it and getting rid of the bad ones that are messy and cluttery.

A good producer is a good editor. Their job is to listen carefully and make thoughtful adjustments or no adjustments. Sometimes it just comes out right the first time and you have to be able to know that. And you have to know when to stop. Some people made everyone stay in the studio way longer than they should have.

Just ask those who worked with Steely Dan.

Or Little Feat with Lowell George, although there was a touch of bi-polar disorder that we didn’t realize at the time. I was involved in one of those marathons.

You said earlier that not enough tracks was a challenge, what else?

I always felt the recording process was wonderful. It was the touring I felt was challenging. I loved to record because you always had a chance to make it better. If you couldn’t improve it enough or fast enough, you dumped it and went on to something else. I could stay in a recording studio for 12 hours without any windows. I didn’t like windows in a recording studio. In my house I have to have them everywhere; natural light is really important to me. But in the recording studio, I would sit under the console just to be out of the way.

That’s quite the image!

I spent a lot of time under there. [Laughs.] Like a dog, so you don’t step on his paw. Because there’s a lot of waiting around. I listened during that time. I listened to the guitar sound and what the drums sounded like in the room, and I knew the things you could put on them.

I had to make up names for the different machines that added different effects—like there was one machine I called the Blockhead machine. It had a series of numbers and letters I could never remember, but I’d say, “Put the Blockhead machine on it.” I can’t remember very well now, but I think it put some echo on things. And there was one that had certain levers that I called the Fruit machine, which did various things to the vocals. At the time I knew how they effected the instruments and the vocals, so I’d say, “Add the Fruit machine, add the Blockhead machine.” [Laughs.]

Did you have a favorite vocal mic?

Oh, man, I had a rebuilt Stephen Paul and it was just really good for my voice. I used it for all the Nelson Riddle records, and on the second record it broke right in the middle of a vocal take. We got the same kind of mic, and even though we got Steve Paul to rework them, we never got that same sound. Every time a new mic would come into business, we would try it. We would actually blindfold test them, and I would always pick out that one mic.

It’s pretty stunning that you never had a vocal lesson until Pirates of Penzance.

I knew how to sing in the chest voice and I knew how to sing in the little head voice, but I didn’t know how to sing in the mixed voice, and I never really learned, to tell you the truth. [Laughs.] What she taught me was not how to sing, but how to warm up and how to bring in my head register. Singing eight shows a week, which you do on Broadway, I worked on that upper register and brought it into my head voice, which freed me up to do the standards.

So how on Earth did you even think you could sing Gilbert and Sullivan?

I sang it when I was a little girl. I sang it in a little, unenergized boy soprano voice. My brother was a boy soprano and that’s what I had to copy, but I knew all the songs. We didn’t have recordings of them. Just my mom played them on the piano. I never got it to sound like a grown-up lady soprano. I still sounded more like a boy soprano, but that was the best I could do.

Was I correct in picking up from the documentary that you really don’t know Spanish so you had to learn all the proper phrasing for the Mexican music?

I know it, but I don’t speak it. I have a good accent. Spanish was spoken in my home, just not to us. The adults used it as a language of privacy. My dad sang in Spanish, and we sang harmonies with him. I knew all those songs, but I had to learn all the words and all the phrasing. I wrote the English right over the words so I knew everything I was singing.

That had to be really hard.

That was hard. That was really hard. I didn’t realize how hard it was going to be. I had known the songs for years and heard recordings of them by really good singers and thought, “I’ll never be able to do that, but I’m going to try.” And then I did. And on recording days I’d be up at 6 in the morning running through those songs. I’d really learn them in the studio, and the guys in the mariachi band would help me. Some of those rhythms are counted in 6/8, but they’re kinda 6/8-and-a-half, and they’re very hard to count. I don’t read music and I don’t count very well anyway. I can’t count to five. [Laughs.]

Are there certain songs that bring you joy when you think of them?

I did my best singing in the late ’80s and early ’90s in the studio. I don’t know if I recorded the best songs and I don’t know what anybody thinks of those records. I don’t listen to them, but I remember singing and feeling very free, like I could do anything I wanted. Learning the songs was always the biggest challenge of recording because I didn’t know if I could sing it until I sang it.

You don’t get a chill when you hear “Long Long Time?”

A chill of disgust. I hadn’t learned the phrasing yet. I needed to learn it on my guitar first, and I didn’t have time to do that before we recorded it. There are some live versions that are a little better. Listen, some things are better than others. Unless you’re Stevie Wonder. He was great when he broke out of the egg.

What did you think of the state of recording as you watched it grow?

The first recording I made with my brother and sister in Tucson was 2-track. Then my first record, Different Drum, was on a 4-track machine. Then we had 8-track, then we had 16-track, then 24-track, then 48-track, and then digital with unlimited tracks.

I made a whole album in my basement in San Francisco—a baby record—called Dedicated to the One I Love. It won a Grammy. There was a lot of layering on that record. There would be 30, 40 vocal tracks on one track. I did everything in a soft voice with Rees harp and strings. We sampled a heartbeat. My daughter was sucking her pacifier; she was 1 then. We had her suck her pacifier into the microphone and made a sample of it, and we used the heartbeat and baby sucking a pacifier for a rhythm track.

You have two children. This is how motherhood changed your life, huh?

[Laughs] I got tired of having to sing to them at night, so I made a record they could fall asleep to. This is the only record I ever made that I listened to a lot after I made it. Every day at naptime we’d pull out the record. It was only about a half an hour long. They’d go right to sleep; it was like they were bored by my singing.

How did you feel about all the technology changes?

There became so much stuff out there it was hard to find your way through it. I don’t know how an artist like Billie Eilish manages to emerge, but she did. She made her record in her bedroom like I made mine in my basement. But in those days when I was recording there were record labels and they were gatekeepers, and the sensibility of a record guy like Joe Smith made a big difference of what the field was and the music that came into the public awareness. Now there are no gatekeepers.