Jazz saxophonist Dave Koz stands beside the console, listening to a mix in Rickey Minor’s new Red Lotus Studios on the historic Sunset Gower Studios lot in Hollywood. The pair, along with engineer Allen Sides, cut six songs in one day, two weeks prior, and five more the following Monday, for Koz’s new Christmas album. “My head is still spinning,” Koz admits.

It’s nothing, though, for Minor, who also records weekly singles for each of American Idol’s Top 10 contestants. “When Dave came in here, they were so impressed that we were 12 songs in in two weeks,” the producer states. “In two weeks, we normally have cut, mixed and mastered 20 songs. So this is Club Med for us!”

Minor has mastered a workflow that allows him and his team to churn out multiple tracks at breakneck speed, without sacrificing quality or creativity. “Even though we work in a short period of time, there are no shortcuts here, from a quality standpoint or from an aesthetic or artistic standpoint,” says Sides. Adds Koz, “This might actually be one of the highest-quality recordings I’ve ever done.”

Red Lotus is Minor’s second home-base studio since 1998, when he wrapped up a 10-year stint as Whitney Houston’s musical director. “At that point, I was 39 and I just wanted to come off the road,” he says, noting that he started at age 19 with Gladys Knight and the Pips, and later with The Temptations, The Four Tops, Natalie Cole and Al Jarreau.

While working as musical director for the syndicated Motown Live, he decided to set up shop—a studio and office—at Hollywood Center Studios, where the show did its post work. “I just love being on a movie lot,” he says. “There’s a synergy there.” He eventually became musical director for American Idol, from 2005 to 2010, before taking over for Kevin Eubanks and leading the Tonight Show Band for Jay Leno thereafter, until its finale this past February, when he returned to Idol. “The Tonight Show ended on February 6, and I started Idol on February 3,” he laughs.

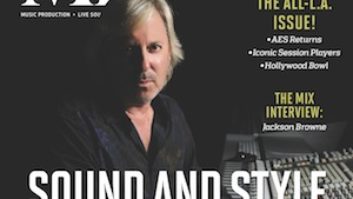

Producer/engineer Allen Sides, right, with Minor at Red Lotus Studios.

Photo: Ashley Stagg

Minor had given up his digs at Hollywood Center in 2011 while working on Leno, so he began looking for a new place, originally for an office. “I was two days away from closing a deal at Paramount,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘I should call Allen Sides and have him take a look at this space, to see if he thinks it’s something I could build out into a studio.’”

The deal didn’t happen, but Sides, longtime owner of Ocean Way Recording, had just sold his space, along with some associated buildings just behind it, to Sunset Gower. He suggested that Minor take over a spot on the first floor of a three-story building there. “Rickey called me, and I knew Sunset Gower was looking for a tenant. So it was a match made in heaven,” Sides recalls.

After going through the concrete building, a former film vault, with Sides, Minor decided to take the bottom floor for his office. “Then I thought, ‘Gee, I need a studio more than I need an office!’” the producer laughs. Fortunately for him, Sides had previously considered building a studio in the space, so the two started off on the same page. Sides then designed and built the studio out to fit Minor’s needs.

The building, without partitions, is long and narrow, but eventually afforded Minor a 17.5×19-foot main live room, two iso rooms (a 9×8-foot “performance room” and a 9×9-foot guitar room), and a 14-foot-wide by 26-foot-deep control room. Though the rooms make use of ample splays and absorption materials Sides had incorporated over the years at Ocean Way, he and Minor didn’t shy away from the effects of the concrete structure.

“I wasn’t concerned about the high ceilings and hard surfaces,” Minor says. “I wanted a project space where every recording would be a master, not a demo recorded in a space where the acoustics make it unusable. When you listen to the tracks that are done in here, you’d think they were done in a very large room. It’s a very neutral sound. It’s clear and very neutral, with no resonances. Remember, I’m across the hall from Ocean Way Studio A and B. There are so many other places I can go [if I need alternatives].”

Sides built a raised floor for the facility. “It has a little bit of bounce to it. It’s not a totally dead floor,” he says. “It has a lot of life to it, actually.”

For the iso booths, Minor wanted complete isolation, with double sliding-glass doors, and he wanted flexibility so that he could alter each space by adding baffles or hard surfaces to change the amount of reflection. “The iso’s turned out great—the isolation’s ridiculous,” says Sides. “We’re doing acoustic bass, acoustic guitars and percussion. So we needed to have very short decays and controlled ambience in each of them.”

The lounge space, a former storage room, is also available for recording, accessible via tielines. “We record Dave’s saxophone parts in there, and it really sounds great,” Minor says. “It’s a pretty live space, but with double blankets surrounding him, we have a little bit of the ambience of the room, but mostly direct sound.” And the space is comfortable.

“You don’t find many new studios being built in Los Angeles that are not in people’s houses,” Koz relates. “At its core DNA, it’s an amazing Allen Sides-created room. But it’s so comfortable, it feels like a house, even though it’s actually a commercial space.”

From L to R: Billy Childs, Rickey Minor, Johnny Mathis, Dave Koz, Allen Sides (behind Dave), Chuck Berghofer, Clayton Cameron and Ryan Staples

Photo: Ashley Stagg

The ample control room had two design needs: to fit the console and fit all of Minor’s various VIP guests. “Rickey needed a pretty big control room,” Sides notes. “He has producers, directors and label people here all the time. And even though it’s not a huge space, you can sit anywhere in the room and it sounds great. That’s what we really wanted.”

He and Minor worked up several configurations to accommodate the room’s good-sized mixing console. “We started out thinking about having a Pro control. But we just love analog consoles,” Sides says. The one that found its home at Red Lotus was one that Dr. Dre had been using at Record One, a 72-input SSL J Series desk. “It’s one of my favorites,” Sides says. “It was the original Todd-AO scoring console, and it’s probably the most expensive SSL ever built. It was a $1.6 million J, with a full film section. We mixed Avatar on this console.”

Sides is particularly fond of its ability to conveniently group inputs together for easy effects sends. “Every bucket of eight can be selected to its own group of aux sends. So you can do eight 8-channel stems simultaneously. It’s a very sophisticated console, and it’s the only one like it.” Though the control room has Genelec monitors available, most listening is done on a pair of large Ocean Way HR2 speaker systems. “They work well, even in a deep control room like this,” Sides says. “With these speakers, there’s no single sweet spot—10 people sitting anywhere will hear everything with great clarity. If you play something that’s well recorded, it sounds amazing. And when you play something that’s poorly recorded, you’d rather not be in the room. If it’s the slightest bit harsh, or there’s anything wrong with it, you’ll hear it, and you’ll fix it.”

Fast-Paced ‘Idol’ Play

Construction on Red Lotus began in September of last year, with wiring beginning mid-January for a month, and the first recordings for American Idol taking place the third week in February, with the selection of the “Top 10” contestants. Each week, the survivors perform a new song live for the audience, after which host Ryan Seacrest suggests the audience purchase a full-length, studio-produced version of that track on iTunes.

The process for creating those recordings on a weekly basis—10 of them to start with, and whittled down over the following weeks—is, to say the least, mind-boggling. It’s also a pace in which Minor thrives. “I love it,” he says. “It forces you to make decisions. You can’t sit around.”

On Friday mornings, after the elimination of one performer the previous night, contestants meet with one of three Associate Music Directors and Vocal Coaches to which Minor has assigned them to work. Possible song candidates for the following week’s program are discussed, and the teams prepare rough arrangements, from which a final selection is made. A piano vocal recording is then made, along with a sketch chart, which is sent back to Minor by 1 that same afternoon.

By 5 p.m., Minor has reviewed all of the songs, deciding on any changes in the arrangements and any special treatments, such as strings or other instruments, that will be required for each. “We have a conference call, and by then I’ve figured out, things like, ‘the intro needs to change,’ ‘no modulation in the chorus to make it feel like it’s going bigger,’ ‘add a 2/ 4 bar here,’” he explains. A team of arrangers, then, works through the night, delivering completed charts and miscellaneous tracks to Minor by 7 the next morning.

Recording begins on the rhythm tracks at 8 a.m. Saturday, with engineering handled by Sides. “He would help me out and give me advice,” Minor explains. “Then I would call him with a question, and he’d say, ‘I’ll be right there’—and he lives in Santa Barbara! He started helping me in the beginning, when I was looking for engineers, and it went from there. I haven’t done one session yet without him.” Lenny Wee, who’s worked with Minor since his Hollywood Center studio days, also works as a Pro Tools technician, arranger and conductor.

The players are all musicians with whom Minor has worked for years, supplemented by any special needs (e.g., pedal steel, banjo for country tracks), provided by longtime contractor Ernie Fields, Jr. “Ernie hired me for my first job at 19,” Minor recalls. “He’s Number 1 on my speed dial.” Recording 10 tracks in one day presents its own set of challenges, not the least of which is assuring that each song has its own character, avoiding any generic “house band” sound, something Minor credits to not only the variety of songs themselves, but to great players. “My guys are so well-diverse. If it’s acoustic guitar, nylon string, pedal steel, baritone guitar, drop-D tuning—they can do anything. But the songs themselves, for the most part, have dictated the individuality of the recordings, giving them a color of their own.”

Minor will vary the instrumentation, based on the song or genre. “We had a girl this year who sang like Stevie Nicks. So I would use a Fender Precision bass, or a 5-string 1968 Gretsch bass that I have.” For another contestant, who did Led Zeppelin’s “Dazed and Confused,” “we did a lot of effects on the vocals, like backward effects, and made it dirtier. And I played an old 4-string Telecaster bass; it was noisy, and I loved it. And it was a perfect fit, to help it sound authentic.”

Minor on the set of American Idol.

Sides will keep the effects paths set up for quick playbacks. “Rickey likes to hear it like a finished record the second we track it,” the engineer explains. “When they walk in for a playback, I’ve got all my ‘verbs, patch delay, everything’s all set up so it’s accessible. We’re very big on that. Because if it needs an overdub or needs a fill, we need to know what it’s gonna sound like as a finished record. The concept of a ‘rough mix’ doesn’t exist, from our standpoint. By the time I’ve heard it twice, it sounds like the finished record.”

The first four contestants begin recording their vocals by noon. The vocals are recorded across town in three rooms set up at the Sunset Marquis Hotel, where the contestants stay, tracked by experienced vocal producers who know how to get the best out of the young performers. “We have three different vocal setups, with good mics and mic pre’s,” Sides says. “It’s all happening simultaneously.”

Minor and Sides, meanwhile, prepare 2-track mixes of the songs and upload them, along with a Pro Tools file, to an FTP site for the engineers back at the hotel. Again, no “rough mixes” here. “We want them to sing to something that really sounds good,” Sides informs. “We try to get it really close to where it needs to be, so that they can have as much inspiration as they can to motivate their performance.”

The completed vocals, comped and ready to mix, are sent back to Minor, and any additional overdubs are added by engineer Steve Genewick, who assists Sides in the final mix, which begins Sunday at 10 a.m. and finishes the following day. The tracks are then mastered for iTunes the following morning, then provided to iTunes by noon that day, and made available for purchase the following night, after the live performance. “It’s intense,” says Sides. “You have, like, three 14-hour days in a row. But it’s very enjoyable. We have fun.”

Rapid Sax

A similar process was put into play for Dave Koz’s Christmas album sessions, though with a slightly more generous schedule: six songs, then five, tracked on two consecutive Mondays, respectively, with overdubs in between (a 12th tune with Johnny Mathis was done during the first week, in Ocean Way). “I don’t understand taking six months to record a record, and then mixing for several months,” says Minor. “You mix all the heart and soul out of it.”

Koz’s disc is in the “duets” vein, with superstar vocalists and musicians accompanying the saxophonist on each track—Mathis, Gloria Estefan, India.Arie, Trombone Shorty, Fantasia, Heather Headley and others. Such albums, Minor notes, can be time-consuming to put together. “You’ve got the arrangement to do, the artists agreeing to do it, then arrangement approval by both artists, and all of the paperwork and red tape.” Minor’s same stock troupe of talented musicians were put to work, again, easily slipping between genres, as required, be it jazz, swing, rock or pop. Still, Minor is not averse to replacing a player if there’s a better fit, even if it means swapping himself out as bass player on five tracks to bring in veteran standup bassist Chuck Berghofer.

“On India’s track, ‘I’ve Got My Love To Keep Me Warm,’ which is kind of an ode to Ella Fitzgerald’s 1958 version, there’s Trombone Shorty, and it’s just a quartet,” he explains. “We made it a little more New Orleans vibe, and I played electric bass. But I knew an upright would sound more authentic. It’s about the truth; you have to let the music dictate what’s best. And all my guys know that’s the case. If I can fire me, I can definitely fire any of them!”

“It’s a hotbed of activity here,” notes Koz. “It reminds me of what the Brill Building was, way back when. And Rickey’s at the center of it all. He knows exactly who to call, and he knows who to call that can come and be there in 30 minutes. We needed Chuck to do this overdub, Rickey calls him, and he says, ‘I’ll be there in 30 minutes.’ And he was here with his bass in 30 minutes, and the overdub was done.”