Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis have spent just about their entire lives making hits. The duo met as high school students in Minneapolis; in 1980 they formed funk/R&B outfit Flyte Tyme, which evolved into The Time and led to their association with Morris Day and PrincePri. But by the early ’80s, their performance careers took a back seat as they became sought after as writers and producers.

In the ensuing decades, Jam and Lewis produced chart-toppers with Boyz II Men, Usher, Mary J. Blige, Mariah Carey, Human League, Lionel Richie, Luther Vandross, Karyn White, George Michael, Elton John, and, most famously, Janet Jackson, in a partnership that began with 1986’s blockbuster breakthrough Control and continues today.

Ever explorers in the studio, they defined the sound of New Jack Swing, always creating at the cutting edge of technology, squeezing every ounce of soul out of machines like Roland 808s, the LinnDrumm and Oberheim synths as they shaped that sleek, sophisticated, signature sound that feels as fresh today as it did four decades ago.

Along the way, they’ve earned five Grammys, 16 Billboard Hot 100 Number Ones and more than 100 Platinum certifications; they were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and won the Legend Award at the 2019 Soul Train Awards.

But their imprint goes far beyond songwriting and producing. They’re businessmen, philanthropists and artist advocates, in their own work and in Jam’s role as Chairman Emeritus of the Recording Academy.

This spring, the duo will release Jam & Lewis Volume One, a compilation of original music that’s been 35 years coming. The record showcases legendary R&B artists at the peak of their craft, including Usher, Mary J. Blige, Boyz II Men and Toni Braxton; the first single, “He Don’t Know Nothin’ Bout It,” featuring Babyface in fine slow-jam form, was released in November. The album is a celebration of the iconic musicians who shaped modern R&B, it’s an ode to the craft of songwriting, and it’s scorching hot.

Mix sat down with Jam and Lewis to learn how their relationship has evolved with technology, how they guide creative collaborators to their full potential, and why they’re finally ready to step into the spotlight as artists.

How have you been working this past year?

Jam: We’ve been using everything from Zoom to a whole bunch of different things. The engineer will set up at our studio when we’re doing mixes. We’ll be listening to the audio that he’s playing; we’ll be on headphones or on speakers and we can make little tweaks and little suggestions. We’ve been finishing the record like that for the most part—which has been cool, actually. It allows you to concentrate on it in a different way, which is kind of interesting.

We have been doing some projects where we actually will go to the studio and all work together, socially distanced and masked. Mostly, we’ve just been utilizing the technology.

Lewis: It’s the age of traveling without moving. The main tool we use right now that’s the simplest is probably Audiomovers Listento, which is just a plug-in–based app that you plug in on a fader, and then broadcast. There’s another really good one called Sessionwire that works really well, it’s just harder to set up.

This new record has been percolating for a while. Did the recording sessions take place pre-pandemic?

Jam: Yeah, a lot of these songs started pre-Covid. The seeds of the idea actually started 35 years ago. We were getting ready to start working with Janet on what turned out to be the Control album; we thought we would do a Jam and Lewis album of some sort, and we’d started working on tracks for it. When we thought we were done, John McClain, who was the A&R person at A&M Records at that time, came to Minneapolis, we played him “Control” and “Nasty” and “What I Think of You.” We’re playing him all these records that we think are hit records, we think are good records. And, like all A&R people, he says, “I just need one more.”

We said, “Let us play you some stuff from our album that we’re working on.” About the third track in, he goes, “Wait, that’s the one I need for Janet.” We said, “No, that’s for our album.” He said, “No, I need that for Janet. Play it for her, and if she likes it, give it to her.”

So the next day we went to the studio, we just put the track on, we didn’t say anything to her. She’s listening and we’re watching her listen. When the song goes off, she goes, “Who’s that for?” We said, “Well, you, if you want it.” She said, “Oh, I want it.” That song ended up becoming “What Have You Done for Me Lately.”

So, that basically launched her career and basically ended ours. Well, it didn’t end ours, it postponed ours. Our album, anyway.

That was in 1985. In the interim, we would get with certain artists who we thought would be great to work with and we’d say, “Hey, let’s do a song together.” Then we’d do the song and the artist would go, “Oh no, we’ve got to keep this. It’s too good, I need this for my album.”

We finally got selfish about three years ago, when we got inducted in the Songwriters Hall of Fame. We called a bunch of the same people we had been trying to call, and said, “We need to do this for us now.” Finally, it’s coming to fruition.

The music feels like such a celebration of artists of an era, but it also feels modern and it sounds like an album. How do you preserve an artist’s essence while keeping things cohesive when you’re working with such a breadth of talent and styles?

Lewis: The easiest way to state it would be, understanding what the key ingredient is in a record, which would be the artist. We tap into the artist, and we write based on that, and we produce based on that, and then we finish based on where we are in time. The technology kind of dictates where we are in time, the sounds, and all of the different things that you can do.

One thing great about Jimmy Jam, he is the texture guy. He can do infinite layers of things. Sometimes I call it the kitchen sink approach. You can’t really recognize what it is, but it feels right.

I think that’s always the effect that you shoot for. It’s not necessarily what sounds good, but what feels right. And then we try to write songs that reflect where the artists are in their lives. To me, style wins over everything. That style is so important because you know, when a record comes on, you can recognize who the artist is right away by how they approach that song. That’s what makes a star a star, or a superstar a superstar.

Jam: There’s an elegance to the album, I think. We’re treating the music with the highest reverence we possibly can, and that can be in the form of the traditions of songwriting. It’s not like you know in the first four bars what the song’s going to be. The song kind of lays out luxuriously. It takes you on a journey. I think songs should do that.

Did you always envision making guest artists front and center?

Jam: What we do is, we write and produce. We do play the instruments, and we shape the songs, produce the songs, write the songs, arrange the songs, and so on. That part of it was really what we felt was our strength. The idea was, find artists that we loved working with in the past, or artists who we had never worked with that we wanted to work with.

Then, the intent was to give songs that, first of all, we loved, but also would make you remember why you fell in love with that artist for the first time. What was that song that made that happen? Let’s do something that gives you that feeling. It doesn’t have to sound like a song that they did before, but it just gives you that feeling.

You’ve clearly found so much inspiration in music technology. How has technology informed the way you work together?

Lewis: It’s kind of a twofold thing. It brings an ease to working together, but it also brings an uneasiness because it gives you so many different ideas for what you could do, so the possibilities increase, and then you’re having to sort.

In the past, being confined made you make decisions based on the moment. You didn’t leave it to chance. We would mix down the background to make sure that the stems all sounded like we liked it, the day that we did it, instead of going back and having the engineer change the balance.

Now, with more possibilities, you can do more with less and you don’t always need to be in a pronounced space or the studio. That part of it is really fantastic, but I think technology complicates things sometimes when it doesn’t need to. We’ve been doing it long enough where we know how to let the technology only do what we need it to do, instead of taking it to the next step. With that in mind, the record that we are making now, I don’t know if 20 or 30 years ago we could’ve made.

Jam: We didn’t know enough.

Lewis: Still, it’s about the people. The one thing that we’ve always said is, buildings don’t make hits, tape machines don’t make hits, people make hits. So how you interact with people is always the catalyst that we start to build from.

As technology gets more complex, it can sometimes be challenging to find that balance where your tools are serving you, not the other way around—especially when the lines blur between production and performance.

Jam: With that in mind, even with drum machines, we always tried to keep a human element to it in some way. We would never really sequence whole tracks; we would sequence maybe a beat of some sort, but then there would be fills that would happen that we’d play live.

The whole idea of a loop-based song simply being a two-bar loop or a four-bar loop playing throughout the whole song, that really never was the idea. Even if we were going to do that, we’d always add what we call “pings and zings.” We’d always put in live percussion, cymbals and things to keep it human.

For us, it was always finding the balance between those two things and thinking of the parts as performances. To me, there’s a magic in that, that we love.

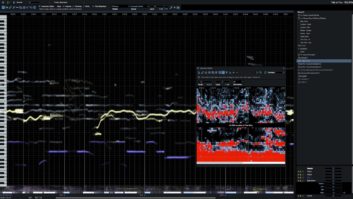

We never were scared of technology because Terry was great. I remember, back in the day, before DAWs were really happening big time, you had… What was the one you had?

Lewis: Soundscape.

Jam: This thing was the slowest, most glitchy, crazy… It was horrible and I kept going, “Terry, Terry, what are you doing, man? You’re wasting your time.” Terry was like, “No, no, I’m going to figure this out.” I remember when we got a Synclavier—at that point, it was the digital tape machines, it was the Sony machines, the Mitsubishi machines—and our engineer Steve Hodge said, “Don’t get a digital tape machine. In five years, it’s all going to be hard disk. There won’t be a tape at all.”

I remember Sonic Solutions, we had that. Then, of course, Pro Tools. All of a sudden, rather than going to The Mastering Lab with big, half-inch tapes, we went with a little DAT. At one point, we just went with a little hard drive. The fact that we were watching that evolution happen and being a part of it, has been so cool for us. We couldn’t have come up at a better time.

At the end of the day, I don’t care how good of a plug-in you have, you just get a good guitar player, with a good amp, and mike it, and that’s exactly what you want. The ability to be able to do all of those things is what Terry’s alluding to when he says 35 years ago we couldn’t have made this record. Because we just didn’t know enough. We didn’t know what we didn’t know.

Lewis: It’s about understanding all of those things. You have to have a reference to start with. When we started, there were no drum machines, so we know what drums sound like in the raw. We know what they sound like miked. We know what synthesizers sound like, we know the different timbres that they give. That can hamper you, too; by knowing, you don’t venture out into the other space. We’re fearless because we know it’s okay to go outside that space; we don’t really try to stay in the box. At least we know what the box is.

Are you as hands-on with tracking as you are with programming?

Jam: Yeah, because, once again, it’s about experimentation. That’s the reason we built our own studio. The advice we were given was, “No, don’t build your own studio.” But for us, it was like, “Why not have a place we can go to anytime we feel creative and just work?” There was an engineer who basically walked out on us at one point, so we had to learn. We would blow up headphones and blow out speakers. It was trial by error. But it was important that we were self-sufficient, that we felt like we’re not going to ever be dependent on someone.

Jam: Yeah, because, once again, it’s about experimentation. That’s the reason we built our own studio. The advice we were given was, “No, don’t build your own studio.” But for us, it was like, “Why not have a place we can go to anytime we feel creative and just work?” There was an engineer who basically walked out on us at one point, so we had to learn. We would blow up headphones and blow out speakers. It was trial by error. But it was important that we were self-sufficient, that we felt like we’re not going to ever be dependent on someone.

A quick story about Control. We engineered that album ourselves, but it was because we didn’t have an engineer. The tape machines back in the day, whenever we would record with Prince, we’d always notice that Prince recorded everything in the red on the VU meters. So, of course, when we started recording our own stuff, we said, “We got to do it like Prince, we’re going to put everything in the red.” At the time, everybody was using Studer machines and either SSL or Neve boards. So, you know, we’re hard-headed; we get an Otari machine, we get a Harrison board.

We get all of our equipment together, we’re recording everything in the red. We call [longtime engineer] Steve Hodge and say, “Come up to Minneapolis and mix this record.” He puts on the first song on the 24-track, and we’re all proud of ourselves. He goes, “Who recorded this?” We were like, “we did.” He said, “Everything’s all in the red.” We said, “Yeah, Prince taught us that; he records everything in the red.” He said, “Yeah, but what kind of machine was Prince using?” I said, “I think it’s an MCI.” He said, “Well, here’s the thing. That machine is set up for zero is zero. So if you see zero on the VU meter, it’s zero. Your machines are set for plus six. So that means that zero on the VU meter is really plus six, so the fact that you’re pinning the needles, you’re way out of whack here.”

We were like, “Can it be saved?” He said, “Oh yeah, it’ll be fine. I’m going to teach you guys how to record.” It was a mistake that we made that Steve Hodge saved. The next album we did, that he came up and showed us how to record, was the Human League album [Crash]. It was so much of a learning experience, but we were very hands-on. We would loop vocals and things, we had the Publison machine… I used to DJ, so I was like, “Can’t we just run the vocals over to a half-inch tape and then I could just wild sync it like a DJ? We don’t even need SMPTE code, and we can put it back in.” We were doing all that kind of stuff; it was like a bunch of happy accidents.

Jimmy, in your keynote at a recent DDEX conference, you spoke about the importance of album credits. Credits were a big part of your own music education. Industry efforts to standardize metadata aside, how can we educate music lovers to be curious about the people behind the scenes?

Jam: Yeah, that was our education, that’s how we knew who Steve Hodge was, we knew what Larrabee was, all of those things that shaped our decision-making process of where to record, and where to mix all of those projects. That all came from looking at liner notes on albums. I do think people want to know who made a record. We’re living in the information age; that should be readily available.

Lewis: Especially in a world where music sells everything but itself. Music sells everything, so I don’t understand why it wouldn’t be appropriate to at least acknowledge those who make, create, engineer, whatever, the music. Who should bear the cost of that? There’s got to be a couple pennies somewhere to put the credits somewhere.

Jam: The other thing we’re missing, though, is what I call the ceremony of music. It used to be that effort went into getting music. You used to have to go to the record store, look through the records, pick the one you want.

There was ceremony in getting that record home, taking it out. It had a feel to it, it had a smell to it. You looked at the label going around on the turntable. All of that was distinctive; all of that was going into your mind as you were listening to the song. Then, you picked the album up, and as you’re listening, you’re looking at the liner notes. You’re seeing all these great names of all these musicians, and all these engineers, and all these writers, and all these producers. It makes the experience important.

The way we get music now is, we hit a button, and boom, it’s in our phone and it’s in our earbuds. So there’s not even a thought that it might’ve taken 12 people to make this record. You’re not really giving it the reverence that it deserves.

How do you know when you’ve finished a song?

Jam: The way we know when a record’s done is always when we can’t wait to play it for the artist. If it’s not feeling like that, it’s not done yet. We’re just enjoying the process of doing it. Terry always says, “I don’t want to reach the destination, I just enjoy the journey.”

So we’re just on a journey, and we’re having fun. We joke that we want to be the oldest Best New Artists.