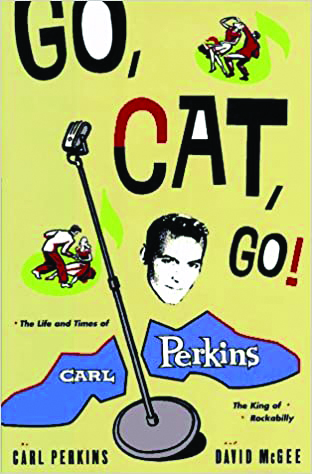

(Ed. Note: Had he lived, rock ‘n’ roll pioneer Carl Perkins would be celebrating his 89th birthday next month, on April 9. The year 2021 marks another Perkins milestone in being the 65th anniversary of the release of “Blue Suede Shoes,” a defining song of the first rock ‘n’ roll era and of the emerging teen culture in post-WWII America. Honoring an undisputed classic and the Original Cat alike, herein lies the tale of how “Blue Suede Shoes” came to be, adapted from David McGee’s authorized biography, Go, Cat, Go! The Life and Times of Carl Perkins, The King of Rockabilly. In keeping with the original text, first names are used primarily.)

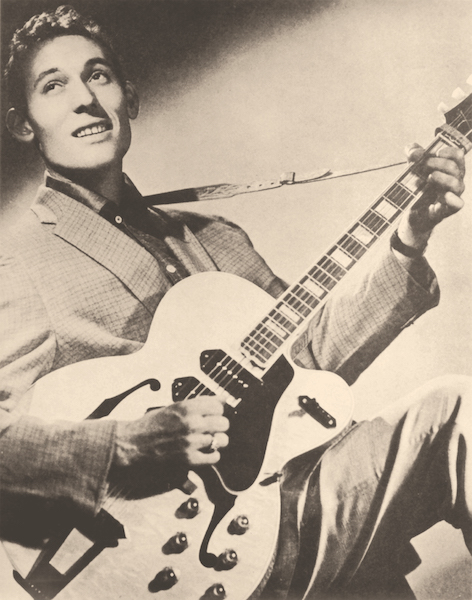

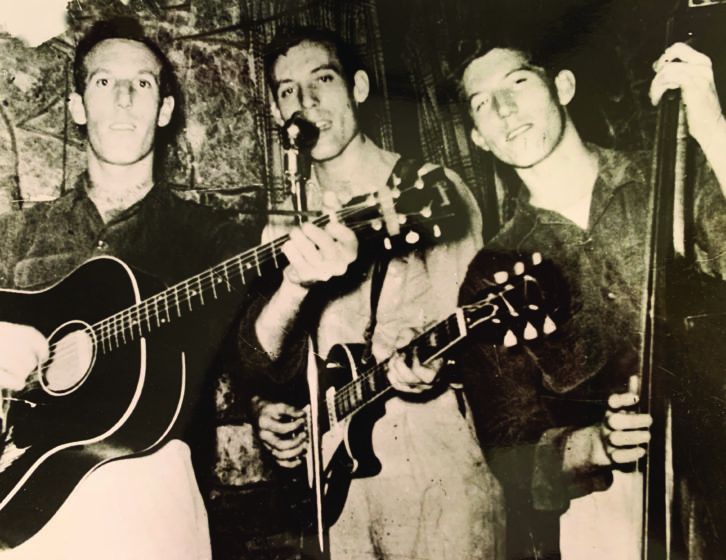

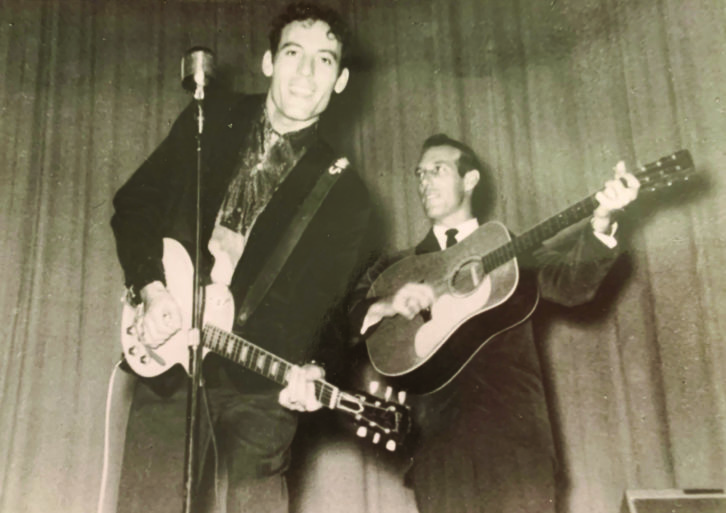

As the humid West Tennessee summer choked Memphis in 1955, Carl Perkins, who had been signed to the local Sun Records label the previous year, had seen his first single (issued on the short-lived Sun subsidiary, Flip)—a self-penned bopping country ditty addressing backwoods Southern dating mores titled “Movie Magg” backed by a country ballad beauty in “Turn Around,” another Carl original—released to encouraging reviews. But Carl (whose band comprised his older brother Jay on rhythm guitar, his wild younger brother Clayton on acoustic bass, and Clayton’s friend W.S. “Fluke” Holland on drums) knew he had more to offer.

Since 1946, when he and Jay began playing as a duo in the honky-tonks in and around their new hometown of Jackson, Tenn., Carl had been refining a new style of music that was both harder than mainstream country and rawer than the popular small combo R&B best exemplified by Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five. Come 1954, he finally heard something on the radio that sounded like his own music: a driving rendition of Bill Monroe’s bluegrass dirge, “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” by a new Sun artist named Elvis Presley.

Duly inspired, Carl, Jay and Clayton journeyed to the Bluff City and, after Carl auditioned with “Movie Magg,” got word from [Sun label and studio head] Sam Phillips to come in and record their first single, “Movie Magg” backed with “Turn Around,” which was released in February 1955. Despite having a record on the radio being such a huge moment for him, one he had been dreaming about from the time he was six and first heard Roy Acuff on the Grand Ole Opry, Carl was getting itchy; as Elvis’ acclaim grew, he wanted to get in on that action with his own up-tempo music, only to butt heads with a resistant Sam, who feared Carl and Elvis would cancel out each other in the marketplace, so similar were their styles.

Finally relenting, Sam encouraged Carl to cut loose, and it came to pass that the second Perkins single, released in August 1955, found another of Carl’s exquisite country heartbreakers, “Let the Jukebox Keep on Playing,” backed with “Gone Gone Gone,” a fiery workout of the type that drew overflow crowds to every Jackson tonk fortunate to have booked the Perkins Brothers Band.

Although Sam was sure he had a country hit in “Jukebox,” Carl was surprised, and pleased, to hear DJs raving about about the raucous flip side during his promotional visits to area radio stations. At almost every stop he was told that “Gone Gone Gone” was “the kind of music the younger people are eatin’ up,” and soon enough it was climbing regional charts as the favored cut.

RAISING ROCKABILLY

At the same time, Carl’s music, along with Elvis’, finally found a name. Over the course of the early Fifties, the style combining blues with country, honky-tonk and/or bluegrass had evolved from “hillbilly blues” to “hillbilly bop” to, finally, “rockabilly.”

It wasn’t all emanating from Sun nor did it magically surface in 1954. In 1939, Washboard Sam, with Big Bill Broonzy on guitar and Ransom Knowling on bass, cut a version of “Diggin’ My Potatoes” that sounds for all the world like what came to be called rockabilly, complete with a shuffling beat and Knowling’s clicking-clacking bass support.

Recording for Decca in 1952, Texas honky-tonker Charlie Adams (vocally a dead ringer for Carl) delivered “T T Boogie,” which blended a rockabilly rhythm with elements of honky-tonk and western swing. In the early ‘50s The Carlisles—brothers “Jumping Bill” and Cliff Carlisle, with George Riddle—cut a bevy of what Bill called “crazy songs” for Mercury, including “No Help Wanted” (1952, featuring jazzy guitar solos by Chet Atkins) and “Zat You Myrtle” (1953), that hit close enough to a rockabilly sound to be stylistic antecedents of the energized outpourings soon to spring from Sun. Lew Chudd’s Imperial label, which had been doing fine with Fats Domino, built a sizable roster of country performers whose music swung toward rockabilly, with Bill Mack’s 1953 single “Play My Boogie” being one early example.

Still, the finest and purest rockabilly came from Sun; Elvis, with guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black, had pioneered it on record, and with “Gone Gone Gone” Carl had brought its rawest form out of the tonks, where he had been refining it for close to a decade, in a volatile environment where to bore was to invite insurrection and injury. Carl still wasn’t sure how to classify his music, other than to identify it as being different.

“I knew I was some form of country, but not Hank Snow and not Ernest Tubb and not Roy Acuff,” Carl said. “I heard something else in that music and worked all my life to find what it was. It’s the way it’s chopped that makes a difference. And the rhythm, the beat, the mixture that’s in it. It’s two or three kinds of music together, is what rockabilly is. And there’s a spirit roaming around in it that keeps it all tied together. Don’t ask me what that is. But you can feel it.”

JOHNNY CASH, ‘CHAMPAGNE VELVET’ AND BLUE SUEDES

With the release of “Jukebox,” Carl was booked for some regional shows as part of a bill also featuring Elvis and Johnny Cash. Their bands met in Parkin, Ark., to kick off a multi-city jaunt. Cash strode into the small dressing room behind the stage and greeted Carl with a firm handshake and a toothy, crooked grin. The two men, now staunch friends, hadn’t seen each other in a couple of weeks. As usual, their conversation turned to songwriting.

“Ain’t nothing worth writin’ home about, John,” Carl answered with a slight laugh when Cash asked him what was new.

“Tell you what,” Cash offered, “I had an idea you oughta write you a song about blue suede shoes.”

Carl had noticed such shoes displayed in shops around Jackson and in Memphis, but he saw no particular cultural import in them. “I don’t know nothin’ about them shoes, John,” was Carl’s dismissive response.

To which Cash related an experience he’d had in the Air Force with a sharp-dressed bootblack named C.V. White, who told Cash his initials stood for Champagne Velvet. Cash’s recollection: “Of course we wore our fatigues when we worked our job in the Air Force, but when we got a three-day pass everybody would dress up in Air Force blues and black shoes. Before C.V. would go to town he would come by and get me to inspect him, because he wanted to look the best he could for those women in Munich. I’d look him up and down and say, ‘You sharp, C.V., you got your shoes shined up really good.’ And he said, ‘Those are not Air Force black. Those are blue suede shoes tonight.’ And he said, ‘Don’t step on my blue suede shoes.’”

His interest flagging, Carl brushed off Cash’s suggestion. “Well, I’ve never owned a pair of ‘em, so I don’t know anything about those shoes.”

As an idea, blue suede shoes seemed to have had its day, at least until October 21, 1955, rolled around.

On that night Carl and the band were booked to play a dance sponsored by Jackson’s Union University at an upscale nightery called The Supper Club. At the appointed starting time of 9 o’clock, Carl, Jay, Clayton and Fluke blazed away on some rockabilly and got the joint jumping. From his vantage point on the tiny bandstand, Carl could see everyone in the room. The energy coming off the dance floor was, as Carl recalls, “electrifying,” with teenage voices laughing and shouting approval of the tunes as young bodies bopped in time to the irresistible rhythmic onslaught.

During a break in the action, as he was fiddling with some gear, Carl got wind of angry words being passed between a young couple near the front of the stage. Turning to the sound of those voices, Carl saw a buttoned-down young man upbraiding his cute date for the crime of scuffing his shoes, to wit: “Don’t step on my suedes!”

IT’S ONE FOR THE MONEY…

The encounter stuck in Carl’s mind long after the celebratory night ended at 1 a.m. Back home in Jackson, he tossed and turned in bed, images and more images playing in an endless loop in his mind’s eye—the crowd’s palpable energy as the music intensified, the couple’s immersion in all the excitement the band ginned up with its heated attack, the girl’s pleated dress billowing up when her beau twirled her, revealing a fine pair of young legs in motion, and always, always, the admonishment, “Don’t step on my suedes!”

In an instant Carl “felt a song writing itself.” Easing out of bed, he crept down the apartment’s cold, concrete stairs into the living room, grabbed his Gibson Les Paul, sans amp, strummed an A chord and hummed a melody he had been hearing in his head. Then came a lyric, built on a nursery rhyme:

It’s one for the money—

He hit a two-chord lick and paused.

Two for the show—

Another two-chord lick, followed by another stop-time measure:

Three to get ready

Now go, man, go!

He broke into a boogie-woogie rhythm and soon had constructed a song’s complete architecture. Rushing into the kitchen, he emptied a paper bag of its Irish potatoes, snatched a pencil off the counter and began writing as fast as the lyrics were taking shape in his mind.

But don’t you

Step on my blue suede shoes

Another verse suggested itself:

Well you can knock me down

Step in my face

What now? “Disgrace my name”? No…had to be a better word. “Slander”! Now that was different.

Slander my name all over the place.

Then back to the key sentiment:

Do anything that you want to do

But uh-uh, honey, lay offa my shoes

Now don’t you

Step on my blue suede shoes

A third verse came easy:

You can burn my house

Steal my car

Drink my liquor from an old fruit. Jar

Do anything that you wanna do

But uh-uh, honey, lay offa my shoes

As he played, Carl heard the arrangement coming together, particularly Clayton’s slapping bass line that would propel the boogie feel. He toyed with a couple of guitar breaks between verses, and continued playing and replaying the song, over and over, trying out different lyric combinations, working out solos. As the sun was rising, he finally fell asleep. When he awoke later, [his wife] Valda was in the kitchen fixing breakfast. Carl dressed, casually emerged downstairs, took up his guitar and started playing the finished tune.

From the kitchen, Valda piped up. “Carl, I like that! I really like that!”

“Well, if you like it now,” Carl answered, “wait’ll you hear it when Jay, Clayton and W.S. join in. If we get it done like I hear it…” His voice trailed off. Deep down he knew the song, whose title he had scrawled on the paper bag as “Don’t Step on My Blue Suede Shoes” (Valda had to correct his misspelling of “swade” to “suede”), was big-league, one that could boost the band to the next plateau, maybe get them out of the honky-tonks for good.

BRINGING IN THE BAND

Following a breakfast more inhaled than eaten, Carl bolted across the street to fetch Jay and his guitar. Jay listened patiently as Carl played his new song. “I hear what you’re gettin’ at, Carl,” Jay said as he strummed the rhythm.

Carl nodded. “You just play that rhythm, man. But remember”—Carl hit the opening stop-time licks—“you gotta hit them stop places like that.”

The brothers started again, but Jay kept blowing the two-beat, stop-time effect. He may have been in mind of the one-beat break in Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock,” but whatever the reason, he struggled with the extra pause Carl wanted. The afternoon passed, Carl patiently worked Jay through the breaks, and eventually it all came together.

Anxious to let Sam Phillips in on the news, Carl called from a pay phone nearby with word of “Don’t Step on My Blue Suede Shoes” being ready for liftoff.

“Is that like ‘O, Dem Golden Slippers’?” Sam asked, referencing the song written in 1879 by African-American composer James Bland, based on an earlier spiritual number, “Golden Slippers,” that in 1878 had become part of the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ repertoire. Bland’s version was arguably the most famous song about “shoes” up to the time “Blue Suede Shoes” emerged.

“No,” Carl answered, irritated by Sam’s diffidence. “This cat don’t want nobody steppin’ on his shoes. Goes like this”—Carl sang the opening and the first verse.

“Sounds good,” Sam replied dryly. “But the title’s too long; it’ll take up the whole label. We’ll call it ‘Blue Suede Shoes’.”

Carl was hot to record, but Sam wanted to let “Gone Gone Gone”/“Let the Jukebox Keep on Playing” run its course. He advised Carl to keep on working and be patient.

Over the course of that Saturday night’s gig at the El Rancho tonk, the Perkins Brothers Band played “Blue Suede Shoes” some eight times, in Carl’s recollection. Not only did the crowd’s response—alcohol-fueled though it was—convince Carl he had a hit on his hands, but the requests to play it again, and again, had afforded the band a chance to work out the kinks in the arrangement, especially those stop-time breaks.

At the end of the night, all Carl could think about was getting into the Sun studio and committing “Blue Suede Shoes” to tape. All the questions had been answered now. This was his moment.

‘I PULLED COTTON FOR MY KIDS’ CHRISTMAS’

Between the time Carl finished “Blue Suede Shoes” and before Sam Phillips summoned him to the Sun studio on December 19, 1955, Thanksgiving came and went, and Christmas loomed. Trying to support his parents as well as his own family of five (Valda had taken jobs ironing clothes for pay to help out), Carl’s finances were bottoming out. Long ago he had vowed that he would give his children the Christmases poverty had denied him in his youth, but the holiday season was looking increasingly grim that year. When he asked Sam if he had any money coming from his recordings, Carl learned he in fact owed money to Sun for his recording expenses.

At his wits’ end, Carl returned to the one place where he knew he could hire on for a few days’ work, take his wages and walk away—a cotton field located on the outskirts of Jackson. He was recognized by some of the other workers, who couldn’t quite believe Carl Perkins was one of their number. Carl collected $15 a day for his efforts and left the experience humiliated and bitter.

“I worked that froze ground and my hands bled,” he recalled. “If that don’t callous you, if that don’t hurt about as bad as anything, to have some ol’ farmer recognize you out there. I’d been singing around here for years in the tonks; everybody around here had seen Carl Perkins. Every disc jockey around here played, ‘Turn Around.’ And when I pulled cotton before Christmas 1955 I had two records. As far as the cotton pickers in this part of the country was concerned, I was a big shot. But I pulled cotton for my kids’ Christmas.”

Finally, December 19 arrived, and once he and the band were set up in the studio, Sam uttered the words Carl had been waiting to hear: “Do me that ‘Shoes’ song.”

The first take was tentative, stiff. Carl changed his original lyric of “go, man, go” to “go, boy, go” and added “I don’t care, baby, just what you do” before singing, “but uh-uh, honey, lay offa my shoes.” His first guitar solo, tepid and sloppy, didn’t cut it; it was the product of searching for some fire but managing only faint sparks. Following the second verse he shouted to the band “Go now!” and cut out on a remarkable solo blending chordings and single-string runs. It sizzled and moved the song forward.

On Take 2 Carl altered the lyrics again; instead of “go, man, go” or “go, boy, go,” he hollered “go, cat, go!” and eliminated the superfluous words from the end of the first verse (making it “do anything that you wanna do/but uh-uh…”). A fiery solo followed, during which Carl, deeply invested in the moment, exclaimed “Aaaah, let’s go cat!” in the middle of the sortie. Before he went into orbit on a second solo that was almost a mirror image but hotter than his second solo on Take 1, he barked out a command for the band to “Rock!”

Vocally, Carl was in freewheeling mode now, singing with an easy but driving swing in his voice and infectious ebullience in his attitude—it was a rockin’ good time in the little studio on Union Avenue. The lyrics were now tighter, more focused, the musicians fully locked into each other, and the whole exercise sounded fresh and lively. Carl had captured the abandoned quality of “Gone Gone Gone,” but also a singular vitality, something different in sound and style from any other Perkins recordings.

Jay, Clayton and Fluke backed Carl with a bedrock rockabilly attack, but Carl’s solos were coming from somewhere else—from country, from blues, from R&B, from all the sources he had absorbed over the years. That Carl and the band had more than risen to the occasion on Take 2 was made clear by a third take that simply couldn’t measure up to the scalding given the song only a few minutes earlier.

Hearing the playback to Take 2, Carl, who had not regarded “Blue Suede Shoes” as his best effort when compared to the craftsmanship of “Gone Gone Gone,” “Turn Around” and “Let the Jukebox Keep on Playing,” sensed the song’s magic. Take 2 was beautiful.

“I felt I had the best rockabilly song I had ever written,” he said. “I liked the beginning and I liked the way I sang ‘Blue, blue, blue suede shoes, mm-hmmm, blue, blue, blue suede shoes.’ That was jive, that was in the pocket, shakin’ ‘em loose, gettin’ ‘em ready to play it again. I felt really good when it was played back through those cheap speakers at Sun. I had a tingle that had never been there before. I looked at Jay and Clayton and W.S. with, I know, a different look. I had to. That was the moment I had really searched for all my life. We pulled away from the studio that night aching to hear that song again. We talked about it all the way home. Jay said, ‘That one might do it. You may have cut something that’s gonna get someplace, Carl.’”

“I went off into deep water on the neck of that guitar on the second solo,” Carl recalled. “Way over my head. I only knew, Here’s my shot. This is my song. It’s cookin’. Get somethin’ outta this box you ain’t never got before. And I did. I never had played what I played in the studio that day. Never. I know God said, ‘I’ve held it back, but this is it. Now you get down and get it.’ I felt all kinds of things going on in me, and I tore into brand-new territory. I was so nervous when it was over. When Sam played it back, it just made my fingers tingle. I’d done pulled my guitar off and was standin’ there leanin’ against a chair. I looked down at it, much to say, ‘I thank my own guitar for what it did. Thank you, boy. We connected.’ I knew it.”‘

‘TOE-TO-TOE WITH THAT PRETTY ELVIS’

Released on January 1, 1956, “Blue Suede Shoes” found an immediate champion on radio in pioneering Cleveland-based disc jockey Bill Randle (“The Pied Piper of Cleveland,” cited by Time magazine as America’s top DJ), who featured the single prominently on his influential nightly show on WERE. Overwhelming listener response translated into brisk sales, and before the month was out Sam received a request from a Cleveland distributor for another 25,000 copies.

That was only the beginning. From breakouts in the South and Southwest, the national demand for “Shoes” grew. Better bookings at a higher rate were an immediate upshot of the single’s popularity. By March, “Blue Suede Shoes” was catching on nationally in a major way. It entered Billboard’s Hot 100 singles chart on March 3, as did Elvis’ first RCA single, “Heartbreak Hotel,” and a week later Carl became the first country artist to appear on the national R&B chart.

On local and regional pop charts throughout the land, “Blue Suede Shoes” and “Heartbreak Hotel” were swapping the Number One spot. Carl was, as he said, “standing toe-to-toe with that pretty Elvis.” In March Sam reported single sales to be half a million.

On March 17 Elvis introduced the song to a national television audience when he performed it on The Dorsey Brothers Stage Show in New York and included it on his self-titled RCA debut album. Near the end of March, “Blue Suede Shoes” achieved an unprecedented hat trick, rising to Number One on most regional charts—pop, R&B and country—nationwide. “Heartbreak Hotel” maintained a chokehold on Number One on the Billboard pop chart, but “Blue Suede Shoes” spent four weeks at Number Two before beginning a slow descent. By mid-April, “Shoes” had surpassed the 1 million sales mark, Sam had presented Carl with a plaque certifying his gold record status and Sun was solvent at last.

Unfortunately, mid-March was the best of times and the worst of times for Carl. On March 22, as he and the band were traveling by car from Norfolk, Va., to New York City to make their national TV debut on The Perry Como Show, their car, driven by a friend of Sam’s hired for the occasion, collided with a truck on a road near Dover, Del., and rolled four times down the road before plunging over a bridge and coming to rest on the banks of a stream. Amazingly, Clayton and W.S. suffered only minor injuries, but Jay’s neck was broken, and Carl’s numerous injuries included a broken collarbone, a severe concussion and lacerations all over his body. Unconscious for two days, and hospitalized for almost two weeks, he recovered, but his career momentum had been dashed on Delaware’s Route 13.

Although he made some of his best Sun records in the years after the accident—including the classic “Dixie Fried” and songs the Beatles would cover in the next decade—his only national hits would be as a songwriter, with “Daddy Sang Bass” for Johnny Cash in 1968 (Number One Country for six weeks) and “Let Me Tell You About Love” for The Judds (a 1989 co-write with Paul Kennerley that was the mother-daughter superstars’ final Number One single before Naomi was forced into retirement by hepatitis).

But his place in rock ‘n’ roll history was secure as an architect of rock ‘n’ roll guitar and a songwriter whose stories were essentially sociological treatises drawn from the cultural environment of poor white Southerners but relevant to all races occupying society’s lower rungs. And in those Sun years, every time he played for the teen audience, he knew that he and “Blue Suede Shoes” mattered in some important and perhaps indefinable way; he knew the feeling from his own youth, from the first time he heard the gospel rave-ups of the Black sharecroppers he worked alongside as a child in the cottonfields of Tiptonville, Tenn.; from the keening mountain cry of Roy Acuff on the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights; from the charge he got from Bill Monroe’s souped-up bluegrass rhythms.

Around the time “Blue Suede Shoes” was burning up the charts in 1956, a young aspiring musician in Hibbing, Minnesota, was beginning to play in public with a rock ‘n’ roll band he had formed with his cousin. Carl’s song “Matchbox,” later covered by The Beatles, was one of the mainstays of the band’s set and Carl was one of this aspiring musician’s touchstones. The young rocker was further energized by seeing, first, the Perkins Brothers Band in concert, and, after the car wreck, Carl backed by a bass player and a drummer. Years later, when he, Robert Zimmerman, was better known as Bob Dylan, he reflected on what Carl Perkins’s music had meant to him in his formative years.

“He really stood for freedom,” Dylan said. “That whole sound stood for all the degrees of freedom. It would just jump right off that turntable; live, it would create such a thump in your belly, you know. Everything—the vocabulary of the lyrics and the sound of the instruments. Where I particularly came from I don’t know a lot of people who listened to it; I think myself and a few of my mates were definitely in the minority. But it made us feel less like wanderers around, that there was definitely a sun out there and a moon and there were celestial elements to life that were being expressed in just a small group of people, like Carl. I guess you could just about count ‘em on one hand. It was everything. It was almost like another party in the room. It was coming from somewhere we wanted to go; we wanted to go where that was happening. As opposed to a record on the radio where it might sound nice but it doesn’t give you any answers or make you think that there are any really. Or any other place to go besides the place you’re perfectly adapted to.”

Go, cat, go!