Tony Maserati

Few mixers have the kind of track record that Tony Maserati has built during the past two decades. He’s worked with everyone from Puff Daddy to Destiny’s Child (and Beyonce solo) to Alicia Keys to Jay-Z to the Black Eyed Peas to Mariah, Mary J, R. Kelly, John Legend, Kelly Clarkson — you don’t have time to hear ’em all!

When former Mix L.A. editor Maureen Droney interviewed Maserati in the December 2001 issue (available at mixonline.com/mag/audio_tony_maserati/index.html), we covered a lot of his early history and some of his specific techniques. In the years since then, he has set up a studio in upstate New York, and he’s greatly expanded the type of projects he works on — who would have imagined him working with his Mix cover compadre Jason Mraz, for example? — and modified his approach to mixing (somewhat) as new technologies dictate. This year, he also spearheaded Waves’ Tony Maserati Signature Series of digital plug-ins (reviewed in the June 2009 issue) based on some of his favorite custom patches.

For this New York AES issue, we thought he’d be a perfect poster boy for New York City’s still vital recording scene — only to learn that he’s considering a shift in coasts. Not to worry, New Yorkers: You probably will still be seeing plenty of this favorite son.

I think a lot of people were surprised to hear you’re considering a move to L.A. Why are you going?

I like to think of it as broadening my base or making my world smaller. There certainly has been a transition — not just by me — in the recording business out of New York. It’s been happening for quite some time. Five years ago, I bought this place in the Berkshires and built a great studio in my barn. My goal was to do 30 percent of my work up here — even if it’s just mix prep work. I’m in the country, I’ve got windows everywhere. It turns out I do something like 85 percent of my work here. There have also been quite a few studio closures in New York City; my home bases are all gone — Hit Factory, where I spent two years in Studio 3; Sony Studio D, where I worked on some great songs. On the Rich Girl project, I did a bunch of mixes at [Troy] Germano’s place and it’s great — an easy transition to and from my studio. But I think much of what makes the business interesting to me has been retained in L.A. — studio environments where I can chat with my colleagues face-to-face about mixing ideas or baseball scores.

I don’t know that I’m going to be a full-time Los Angeles person because I think I’ll always have my spot up here.

So you’re going to keep that place.

Yeah, I’m going to keep the studio here. I may have to move a chunk of the equipment out to L.A.; it depends on where I hang my hat. I like what’s happening out there — a lot of recording going on; guys I know well doing their thing in an environment where you can make deals with studios and camp out for long periods of time, essentially creating a home base. I want that again. And being in a major metropolitan area is definitely beneficial for business. Still, I think down deep I’ll always be a New Yorker.

Do you have a place or situation waiting for you?

I’ve called the Record Plant “home” for pretty much the whole time I’ve been in L.A. I’ve spent as much as eight months at a time there.

I didn’t realize you’d spent so much time there.

While I was in L.A. waiting to start the Black Eyed Peas record [Elephunk], Ron Fair [producer and CEO/president at Geffen/A&M] had me doing work with Christina Aguilera and a couple of other gigs. Between those and the Peas, I was there a long time. I had also worked at Conway and Enterprise.

With the new way that I work, the sound of the room and the environment are really the two most important things for me because, equipment-wise, I’m either going to bring my stuff or I’m going to rent the stuff I like to make a mix happen.

Maserati’s studio is built in a barn on his property in upstate New York.

Photo: Jung Kim

What do you mean “new way you work”?

Upstate, I have all the same outboard gear I’ve been dragging from studio to studio, including a giant Pro Tools rig, for the past 20 years. I’ve got lots of analog compression — I’ve got my LA-3As, my 1176, an old ITI and lots of newer gear like the Chandler TG1. I still sum analog using a Chandler 16-channel mixer, a Neve 12-channel sidecar and a Dangerous 2-Bus. I choose which one I’m going to use directly from [Pro] Tools, depending on the sounds. So typically I’ll use the Neve for my kick, snare and bass. The Chandler handles most of the vocals, guitars and piano. And the Dangerous will pick up whatever is left — keys, strings, etc. The Chandler eventually sums everything before going to my Lavry A-to-D converter and into [Pro] Tools. I’ve also got my [SSL] X-Logic rack, with SSL EQs and compressors. Essentially, I’ve got a lot of analog stuff I use to get my usual analog sounds, but I do all my automation in Pro Tools. And I have a minimal recall time — usually about five to 10 minutes; that’s pretty quick to do a recall.

How is that different from what you were doing 10 years ago?

Ten years ago we had a 96-input SSL J, and recalls could take upward of four hours. My assistant would have to sit there and reset 96 channels of the board. Then he had to reset all that gear and all the patches. Now, even the [SSL] Duality is quicker because it allows multiple people to recall the board.

So it turns out to be a nice confluence of record company budgets shrinking but you being more efficient because of technological advances.

That’s exactly right. It’s helped me be more competitive. I find in meetings that many of my clients like to be able to make changes up until the last minute. I just uploaded files for mastering last night — where the producer is traveling on the road and I’m either streaming to him or sending him MP3s or full bandwidth, depending on how close we are, and he’s able to make comments about parts and edits and things like that in a moment’s notice. I can do a quick change and re-send files for mastering up until the last day, whereas, going back to when we worked with tape, we had to set aside three days to make sure everything was ready; now it’s three hours.

So you’re not using analog tape for anything.

I’m not. I have a half-inch machine, which I can roll out, but the last few times I’ve recorded to tape, either the mastering engineer decided not to use it or the client decided on an alternate pass that didn’t make it to half-inch. It’s a lot of extra work for me and my second, and if they’re not inclined to use it, what the heck are we doing here?

Well, there was that period when some mixers were nervous about completely eschewing that analog tape sound so they brought it in at the end.

That’s true. It was very much a part of my sound — how I manipulated the tape saturation, the compression. I used to call it my “glue,” where my last step was gluing it together with the oxide on my tape, and how hard I hit it was part of my sound. And I actually didn’t hit it very hard, but I chose my level and my bias and things like that, and now I’m thinking quite differently, as you can imagine.

Are there things you’re doing to compensate for not having your “glue”?

Absolutely. I’m doing lots of things. In the days of tape, I was relying on the beauty and electronics of the machine and the things that tape did — the way it all affected my overall frequency content, how the print-through was working either in my favor or against me. So what I tend to do now is I’ll add the things that I remember tape doing — I’ll put really subtle and minute millisecond delays on lots of things — just to glue, and then that gets compressed with my 2-Bus compressor. So I’m thinking about things in that way and trying to replicate some of that glue. Parallel compression; things of that nature.

You do a lot of work on “singles” or featured tracks. How has the definition of what that is changed sonically? One used to sort of mix for the radio, but I don’t know if that’s still the case.

Of course that’s still the case! I came up in the days of dance remixes so, in the same way they mixed a song to be “club-specific,” I learned to be “radio-specific.” I’ve always taken that idea with me wherever I was going, genre-wise. I often think about exactly where my mixes will be played, and it’s very genre-specific. The Lizz Wright record I did was both AC radio and an audiophile kind of thing, so I spent a lot less time listening to it on my computer speakers and a lot more time listening on my audiophile system. Whereas the Jason Mraz [We Sing, We Dance, We Play Things] is kind of going across the spectrum — playing on some audiophile stuff, iPods — so I spent more time on my computer speakers.

Would you listen to a mix on iPod earbuds, the way people used to go to their cars and listen to mixes?

I don’t, no. I do still go out to my car, though. In the studio I have five sets of speakers. I have my Tannoy DMT 1200s. I have ProAc Studio 100s. I have my little Craig Sound computer speakers — these tiny little things with no sub or anything — and my Dynaudio M1s and Snell audiophile towers.

What does mixing on computer speakers tell you as you’re doing it?

Mixing on computer speakers and monitoring with a [Waves] L2 on the mix gives me energy indicators.

Because it gives you a picture of what’s jumping out and being emphasized and what isn’t?

That’s right. I want to make sure that, energy-wise, that vocal is dominant and compelling, and the other parts that are supposed to be hooks — I call them characters — are popping through, whether it’s a bass part or whatever. Even on my little speakers, that’s got to come through. I did a record in the earlier part of the year with a new artist on Linda Perry’s label named Reni Lane — great artist, great production. I monitored a bunch on the computer speakers because so far she’s an Internet baby — she’s part of that new generation of artists that are YouTube-y, viral babies. Their audience is going to be hearing it on ear buds and computer speakers; kids in a dorm room with whatever makeshift sound system they’ve put together.

How do you stay ahead of the curve — stay fresh, current and not fall into clichéd approaches to things?

I don’t really think about it that way. Each record I do is a custom thing. Each record is for an artist at a point in their careers and in popular culture, so I do what feels right for that artist at that moment.

But I will certainly listen and make notes about what my colleagues are doing, the same way I did when I was a young, aspiring engineer and made notes of what Roger Nichols [Steely Dan] was doing, or Bob Clearmountain was doing. Or Neil Dorfsman. Or Bruce Swedien. I have pages and pages of ideas they gave me. I can’t tell you exactly what they did, but what I got out of it made me do something in a certain way, or made me use a piece of equipment because it produced a sound that I thought was similar to what they did. Of course, if I’d actually asked them what they did, I probably would have learned they did something completely different. [Laughs]

These days, I’ll listen fairly closely to the mixers I share space with on an album — if I’m doing four tracks and Spike [Stent] is doing another four and Dave Pensado is doing another three or four, I’ll listen to what they’re doing. I love their work! I find Spike’s work really energetic and very pop-y compared to mine. The way I work with space is different than both of them. So occasionally, I’ll say, “Let me see what I can do to make my chorus have some of that pop-y edge,” or, “Let’s try a long reverb at the end of the verse,” for instance. I’m sure if I asked, they’d tell me. But why call and ask? It’s more fun to listen to their work and try to come up with some approximation. Because more than likely, it’s going to lead me to something that is new and different and mine.

Do you think young mixers coming up are missing something by only mixing in the box and using plug-ins rather than learning on a conventional console and using traditional analog boxes?

I don’t know. That’s a hard question. A good portion of the young guys I talk to — either work with or work on their tracks — are very curious and very interested to know how I use this or that piece of gear. They may not get the chance to use certain pieces, whether it’s a big console or some piece of vintage analog gear because of price or availability. Strangely, there are also all these young guys coming up who are building their own stuff. This guy Zack Hancock, who works at Downtown Studios in Manhattan, is always on eBay or Gearslutz finding amplifiers that used to be in who-knows-what, and turning it into some sort of summing box or some sort of processor. It’s amazing! My second, Mack Burkhart, does the same thing — he’s always hunting down gear and coming up with these weird, esoteric things. He’ll ask me, “What do you know about this kind of tube?” I’ll bark, “What the hell are you talking about? I don’t know about a damn tube! I know you put the tube in and it works and it sounds good.” [Laughs] If somebody really has to know something about that kind of stuff I’ll send them to Dan Zellman, a New York-based guy who seems to have stored all the tech-y knowledge of the past 50 years, or maybe John Klett — same kind of cat. Those guys are inundated with e-mails from 20-somethings asking them about tubes and capacitors. I love those kind of guys. But I do music; I don’t do circuits.

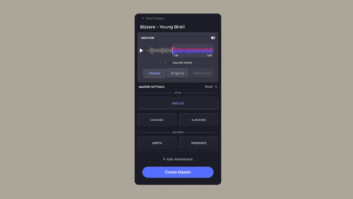

When you design plug-ins, as you have for the Waves Signature Series, what does that entail?

It was an attempt to make some of my ideas — I call them tricks in my pocket, but they’re really patches — accessible to other people. So from a Neve EQ to my LA-3A, then maybe crunching it a bit with maybe an 1176 on a parallel aux — or maybe it’s going to a Distressor, as well. So I said, “I want to create plug-ins that are sets of patches that replicate some of the patches I have been using for 20 years.”

It’s all those elements based on what the compression ratio is, what the attack times are, in some cases even some subtle effects, whether they be delays or reverbs. We approached it that way, and it actually was a lot harder than any of us expected it was going to be because re-creating that analog stuff in the digital world is not always that easy. Digital compression, although getting better, is not the same — a plug-in is not doing quite the same thing that an analog compressor does. So none of them are going to be exact duplicates of what I might use on a daily basis in the analog world. But I think we got close, and I think they’ll be very useful for some people — particularly producers, writers and younger engineers who don’t want to spend all their time coming up with great sounds.

What’s the last piece of gear that blew your mind?

I was at Germano’s place — I was using the Chandler Gemanium box and, man, I still don’t know exactly what it does! In fact, on my list of things to do is to reach out to Wade and see if he can send me the box so I can mess with it. I think it’s one of those boxes you have to spend some time with. I used it on a couple of basses and it sounded great. Another piece I’ve started using is the Smart AV Tango DAW controller — it’s got a touchscreen, and although I’m not as fast on it as my old controller, the unit seems promising.

I’ll talk to my [mixing] colleagues about gear. Jean-Marie Horvat is one of the guys I rely on — he’s such a gear head and really good at picking and choosing good stuff. He’ll say, “You’ve got to try this!” and he’s almost always right. Michael Brauer turned me on to Thermionic Culture and I’ve been using some of their stuff.

Tell me a little about working on the Jason Mraz album.

The year before we did Jason’s album, I had gone to [producer] Martin Terefe’s place in London — Kensaltown — to work with him on a Craig David record, and we became friends. Martin is just amazing — I can’t say enough good things about him. He’s super-musical. He has one of those big lofts, not far from Portobello Road, and a crew of musicians who are around all the time. There’s no control room — he’s got an old API right in the room, and there are buses going by outside from time to time. Martin’s engineer — Dyre Gormsen — recorded the Jason album pretty much live right there. There might have been two or three takes on Jason’s vocals — maybe a punch here or there — but very, very little. Anyway, Martin thought I’d be right for the Jason project. I did a couple of mixes for them, and they loved it. So we went forward with it and I ended up mixing the entire record here at my place.

That must’ve felt like a change of pace for you.

Well, I had just finished a Lizz Wright record with [producer] Craig Street, which was dramatically and sonically complex, requiring tremendous focus. But with the Jason record, no one attended; it was just me and an assistant. I was sending MP3s or full-bandwidth files to Martin and to Jason, who is on the road perpetually. Martin was in the middle of who-knows-what production at the time. We got the whole record mixed and then [Atlantic Records CEO] Craig Kallman and Sam Riback, the A&R guy, wanted to be present and do some tweaks on three or four songs. So I went down to my buddy Hector Castillo’s studio — after maybe 20 minutes of recall time, I was able get back exactly where I was on those four songs. Then Craig and Sam were able to come in and give me their comments and tweak it in a studio environment. So those four songs were ultimately mixed there. But the rest was done at my studio upstate.

I have to admit, I was a little nervous about making alterations — when you get something from someone like Jason, who’s clearly a great writer and performer, you’re always a little leery about making changes, like cutting out part of his vocal or doing an edit, where I hold the drums out till the downbeat of the second verse. It’s a little risky. But if you show that you know what you’re doing, and you’ve got a clear direction for the song, they may just say, “I love that idea!” On one Jason song, there were a couple of vocal parts I tried to nix with an edit. I sent it to Martin and Sam, with a note saying, “I dig it this way. What do you think?” Then I sent it to Jason. I got a single-word e-mail back: “Nope!” [Laughs]

Oh, well, it’s worth the risk, I trust.

Absolutely! You have to take chances.

Blair Jackson is Mix’s senior editor.

Jason Mraz Weighs in on Maserati

The Jason Mraz album that Tony Maserati mixed, We Sing, We Dance, We Play Things, was a huge hit last year (and this year), and even earned a Record of the Year Grammy nomination for the song “I’m Yours.” We caught up with the perennially touring Mraz in Indiana recently to ask him a couple of questions about Maserati’s mixing.

When you were cutting the album with Martin Terefe and Dyre Gormsen, were they doing rough mixes along the way so there was, in essence, a template of how you wanted the record to sound?

Absolutely. If we worked on a song that day, I would go home with a rough mix that night to know what we got. We kind of mixed as we went, so we were always able to listen to the record as we had it in front of us. Then it wasn’t until we gave it to Tony that he really tore the whole thing apart and revealed some gorgeous new arrangements.

Tell me about the decision to hire Tony. I don’t think he was an obvious first choice.

I know [Atlantic CEO] Craig Kallman and Martin were big fans of Tony; they love the guy! And I think they thought the album might be a little too light, so they thought, “If we send it to Tony, we know he can really bring out the rhythmic aspect of this album.” But what they didn’t expect was for Tony to be a fan and for him to really take so much care on this record. I think what he really paid attention to were the stories that were being told and the messages that were woven into the music. He gave us a new perspective.

He worked a lot on the arrangements, took a lot of our layers out, moved things around. “I’m Yours” is the best example. The arrangement that you hear on the radio and on the album is really Tony’s arrangement. He tried little things like bringing in the drums later, dropping them out again in the third verse and a different use of layering instruments we had added. He really stripped that song down to be more like the original demo, which was just guitar and vocals. He did a great job of capturing that, maintaining the truth in the song.

Was it shocking when a mix comes back to you and all of a sudden a part is missing?

No, I was relieved. It could’ve been a shock, but I was so in love with the way Tony was mixing the record and really taking control of these songs as, ultimately, the first listener. He was taking liberties that were extraordinary.

And he said you were frank with him when you didn’t like something.

I remember getting into a little debate with him one time — there was this scat in “Butterfly” that I wrote with the song. Well, on his first mix, the scat was gone, it was just an instrumental section. I said, “No, no, no, we can’t have that!” And he was pretty adamant about why it was important to drop that out because then when my voice comes back later, it’s even bigger and stronger. We went back and forth, but finally he left it in there. I won that one. [Laughs] But all in all, he was fantastic to work with.