“Quirky.” The word invariably pops up in every story written about the venerable British art-pop group XTC, so it’s best to get it out of the way right off the top. And they are a quirky band, though as co-founder, de facto leader and self-proclaimed “benign dictator” Andy Partridge notes, “At the moment, we’re not so much a band as a brand. I mean, now it’s just the two writers-myself and Colin [Moulding]-left. But we carry on, and I think to most people it’s still XTC.”

Though XTC has occasionally flirted with the pop music mainstream and has had a few marginal radio hits, they have mostly survived thanks to a dedicated and still-growing cult following that has embraced Partridge’s and Moulding’s constant musical shape-shifting. XTC’s musical eclecticism has taken them from edgy, new-wavish rock to brilliantly arranged Beatles-esque confections, folk-inspired musings, sly “garden party psychedelia” (as Partridge calls it) and, on their new CD, Apple Venus Volume One, sweeping orchestral-based tunes. Over the course of a dozen or so albums, they have crafted songs about the sacred and the hopelessly mundane, with lots of insight and nonsense in between, and they’ve done it with humor and passion. Partridge, in particular, is capable of being both cynical and wide-eyed almost in the same breath, just as his music moves easily and unpredictably from the most tuneful melodies imaginable to surprisingly dark dissonance. Yes, quirky-but lovably so.

The ’90s have been a strange time for XTC. Besides Apple Venus, which was released last month, the group’s only other effort this decade was 1992’s typically eclectic Nonsuch, produced by Gus Dudgeon, who was reportedly fired from the project after he refused to let Partridge have significant input at the mixing stage. Then, long-festering disagreements between XTC and Virgin, the band’s record label in England (they were on Geffen in the United States), exploded into open hostility, and they effectively went on strike for the next four years. They eventually extricated themselves from their deal and signed in America with the upstart indie TVT Records. In the meantime, Partridge and Moulding kept writing songs. Between them they penned 42 new tunes, 22 of which were intended for a double-CD release. Instead, Partridge and Moulding decided to put out two CDs: The just-released Apple Venus Volume One “is sort of acoustic-orchestral,” Partridge says, “and Volume Two will be simpler electric, head-against-the-wall sort of stuff. You could see my head going in an orchestral way from some of the tracks on Nonsuch, like ‘Rook,’ ‘Wrapped in Grey,’ Colin’s ‘Bungalow’ to some extent, even songs like ‘Omnibus’ or ‘Humble Daisy.’ They’re not your standard rock ‘n’ roll instrumentations.

“When we finished Nonsuch I wanted to get more into the orchestral area, so I bought myself a [E-mu] Proteus and really fell in love with a lot of the sounds. I don’t play keyboards, but I love the inspiration of keyboards. They intimidate me terribly, and if I find a chord, it takes me half an hour to find out where I want to go next. I’m not the fastest kind of busker to sit up in a bar and play the piano! I have a tiny studio-12 by 8-and I couldn’t cram anything like an orchestra in there, so this was the nearest I could get to it. And I started sketching out links and parts and pieces, anything that was inspirational, and eventually some songs came out of this, such as ‘River Orchid’ [opening track on Apple Venus]. That started as a wonderful little loop I came up with. I was literally dancing around the studio after I came up with that loop, making myself really sweaty, and I didn’t want to turn the thing off; it was just lovely going around and around and around. There could be a million songs in that loop, and I wrote three to ‘River of Orchids’-very simple nursery rhythm-type melodies, and wrestled them to the ground, made them fit each other. Then we got a 40-piece orchestra at Abbey Road to play it through.”

That’s the simple version of the story. In fact, recording Apple Venus was a long, drawn-out and occasionally traumatic affair. After a couple of weeks of programming sessions in the fall of 1997 at the Kent home studio of producer Haydn Bendall (BeBop Deluxe, Kate Bush, Elton John, Tina Turner, XTC’s 1977 EP 3D), work on the songs began in earnest at another home studio, this one in Sussex and belonging to Squeeze’s Chris Difford. But Difford’s studio wasn’t ready to accommodate the group (which at this point still included guitarist Dave Gregory, a 19-year vet of XTC and the strongest player of the trio), and after a couple of weeks the sessions collapsed. The action began all over again at Chipping Camden Studios, in the rural Cotswolds region of southern England, in early 1998. This time things went considerably better, with engineer Barry Hammond working with Bendall and the group to put down basic tracks over the course of about six weeks.

“We did months and months of sketching and planning and cutting tracks and replacing them, but because there’s so much orchestral material, most of the album was actually recorded in one day at Abbey Road with the orchestra,” Partridge says. “Then we spent a couple of months editing and tweaking and nipping and tucking. Anything that you record with orchestras and you have a limited time, you just have to make it all with edits. We didn’t used to edit. In fact, I was appalled when I heard other bands doing editing between takes. I thought, ‘Jesus, they’re cheating!’ But you buy any classical album and you can bet your life that every few bars there’s an edit. So we did a lot of work [in Pro Tools] back at Hayden’s place, until he had to quit to work on other projects.

“The latter part of the album, which was the vocals mostly, along with some bass and acoustic guitar, was recorded in Colin’s house,” he continues. “We did it on a Mackie desk. We bought a really nice AKG valve mic, and we bought some really lovely valve [tube] compression and limiting made by Linncraft-the blue boxes-and we bought a Linncraft EQ, as well. So basically we got a lot of nuts-and-bolts, get-it-down stuff. And as part of making the album we also bought a secondhand 24-track Sony digital.” Nick Davis was the principal engineer for the sessions at Moulding’s house, and Davis mixed the CD at Rockfield Studios in Wales.

Somewhere in the swirl of making the record, Dave Gregory decided to quit the group, leaving Partridge and Moulding to complete the disc. Partridge, who wrote nine of the 11 tunes, thinks it’s one of XTC’s best and fully believes that with the strength of a new label behind them, Apple Venus could challenge Skylarking and Oranges and Lemons to become one of their best sellers. Over the years, XTC fans have given the group plenty of latitude musically, so what might seem like a bold stylistic departure to some bands is regarded as par for the course with Partridge and Moulding.

“We’ve never really fit in anywhere,” Partridge says good-naturedly. “We were extremely lucky in the early days [mid-’70s]. The good thing about the punk thing is that the record companies panicked-afraid they were going to miss something-so they signed everything that moved and we got swept up in that. We were doing the same thing a couple of years before and no one would even look at us; they thought we were insane, playing our little three-minute songs-short, sharp, quirky pop songs. People just said, ‘It’s them!’ and the dance halls would clear! Then, late in ’76, record companies started to go crazy and sign up everything. Make no mistake, they didn’t really care who we were. They were looking for tuna and we were a porpoise that got stuck in their net.”

Through the years XTC has worked with a number of top producers and engineers, so I asked Partridge for some brief reflections on those relationships.

On John Leckie, who produced the first two XTC records, White Music (1978) and Go 2 (1978): “We knew nothing about producers, and Virgin Records suggested John Leckie. He’d done BeBop Deluxe, whom we really liked. They were a classy, modern-sounding band. So we went in the studio and John was extremely amiable to work with, and he liked working with young bands-he liked the energy and naivete of young groups. He was young, too. In fact, about halfway through the album he got drunk one night and confessed that this was the first album he’d ever produced; he’d only done individual tracks on records up till then. But he was good. Working with John Leckie was always immensely pleasant, just because of his personality.”

On Hugh Padgham/Steve Lillywhite, the recording team on Drums & Wires (1979): “I felt what was lacking from what we recorded with John Leckie was this feeling that I liked from really old rock ‘n’ roll records-primarily the sound of the slapback echo and the drums, which really exploded. I kept asking people, ‘How did they get the sound of the drums on ‘Jailhouse Rock?’ or whatever, and they’d explain that the drums were recorded in a big room, lots of ambience and loads of compression to pump it all up. And I said, ‘Who records drums like this? Let’s do it!’ Around this time I heard a Siouxie & The Banshees record, and it had really noisy drums on it, a real ’50s kind of sound. And it turns out it was done by Steve Lillywhite, and he came with Hugh Padgham as a team in those days. Hugh was interested in engineering and Steve was mostly interested in mixing, and between us we seemed to get it recorded, with Steve vibing everyone up: ‘C’mon! That’s great! One more take! One more take!’ and Hugh getting these very polished but aggressive sounds. We worked in The Townhouse, which was a relatively new place then, and they had these very live rooms with stone walls and ceilings and the drums sounded really explosive in there. Hugh sort of perfected that sound, and then everyone wanted it-Peter Gabriel wanted it, Phil Collins. It became the sound of the early ’80s. And a lot of it was Hugh working it out on us.”

On Steve Nye, who produced Mummer (1982): “That’s probably the least liked of all our albums. Steve Nye had done a few things we liked, such as Tin Drum, from Japan. He was an excellent engineer, but a little too exacting for me. And he had an incredibly grumpy manner which seemed to depress everyone in the studio. He should really learn to cheer up.”

On Todd Rundgren, who produced and engineered Skylarking (1985): “I wish that Todd Rundgren were a less sarcastic and more amiable person, because some of his other skills are fantastic. I can’t say highly enough what a brilliant job he did. Although, he should certainly work with an engineer, because I don’t think his engineering skills are all that good. But his arranging skills are fantastic and very intuitive. He can come up with arrangements instantaneously and you think, ‘Where the hell did that come from?’ You can suggest something to him and then overnight he’ll go and do it, whereas it might take you months to work something through. He can’t deal with people, but he can deal with music and machines and computers. The two of us were butting horns constantly, but I think that’s part of his nature as a producer. Maybe he feels he has to break people to mold them to his decisions.”

On Paul Fox and Ed Thacker, producer and engineer of Oranges and Lemons (1988): “They were different than all the rest. That album is like having your ears and eyes blitzed by fluorescent chromium or something. There’s a lot going on in there. Paul never wanted to upset us. If we had any ideas, he’d say, ‘Well, let’s record it!’ or ‘Hmm. That might be a good idea, as well. Let’s record that, too. You have another idea for a high-hat part? Let’s give it a try!’ So you might end up with three or four high-hat patterns, two basses. And though we always said we’d choose one, a lot of times we kept several! So there might be a bit much on there. But they both did a great job, and they were very conscientious and very easy to work with; very nice guys. Paul was possibly the most conscientious producer we ever had. He really lived every note. I’d like to work with them in the future; in fact, I’ve expressed that.

“Producers’ personalities invariably color the music immensely. Todd’s sense of order, his sense of arrangement and his rather shabby engineering attractively colored Skylarking. Paul Fox’s extreme devotion to the project, his indecision about what we were recording and Ed’s million-dollar engineering colored that project. So you get the input from the engineer. But input also comes from other sources, as well: You might have bought a new guitar the week before that you want to play. Anything can affect it. New boots. Tight trousers…”

With the first part of Apple Venus finally in stores, Partridge and Moulding are now turning their attention to Volume Two, which Partridge expects will be recorded at Moulding’s house. “This time we’re building a studio,” he says. “We’re sick of throwing vast amounts of money at studios, so we’ve decided to throw it at ourselves and we’ve taken over Colin’s double-garage, which he doesn’t use, and the adjoining building, and we’re bashing it all into somewhere that we can record Volume Two.”

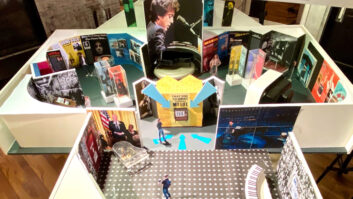

XTC retired from the road many years ago, so don’t hold your breath waiting for a grand promotional tour supporting Apple Venus Volume One. Instead, Partridge and Moulding will skip around the States, chatting up the disc to journalists and on radio. The new CD also coincides with the release of an XTC boxed set called Transistor Blast and an authorized book about the group by Neville Farmer called XTC: Song Stories. Partridge says that in preparation for the book, he listened to the band’s entire catalog.

“It was very strange because it’s nearly all stuff I haven’t heard for ten or 15 years or more,” he says. “Otherwise, the only time I hear my music is if I get so stupidly drunk I get through the embarrassment barrier-the vanity barrier, rather-and I put headphones on and lay on the floor and then I usually pass out after a quarter of an hour, so I don’t get to hear much of it!

“To be honest, I’m not really interested in our old songs. I’m much more interested in the songs I’m working on at the moment and the ones I haven’t written yet. Anything that’s been done in the past-and this is me talking about my ‘art,’ with a capital ‘F’-is dead and gone the minute it’s been recorded. Then it’s for other people to stumble upon and say, ‘Hmm, I like that,’ or ‘No, don’t like that one.’ I’m always much more interested in finding new things.”

Which has kept XTC a vital band for more than 20 years.