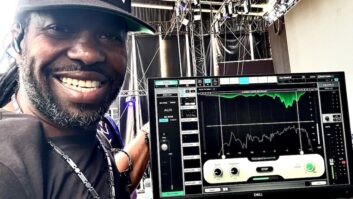

Sean Callery

Photo: Matt Hurwitz

If Sean Callery waits two more weeks, he won’t have to reset the clock in his studio, having never adjusted it last fall at the end of Daylight Savings. “It always makes me think I’ve got more time,” he says.

A clock ticking, time running out. Clearly, we must be in the home studio of the composer who gives Fox’s hit series 24 its incredible sense of urgency, something the Emmy-winning composer has done successfully for seven seasons on the show. With its almost nonstop pulsing rhythms and pounding action cues, Callery’s music keeps viewers on the edge of their seats as they follow Counter-Terrorist Unit Agent Jack Bauer through hour after hour of a day’s worth of suspense.

Callery moved to L.A. in the late 1980s, not long after earning a degree in music from the New England Conservatory. He spent his first five years in town working as a product support specialist for Synclavier. This afforded him interaction with such notable musicians as Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock, as well as scoring composers Alan Silvestri and Mark Snow. Snow (The X-Files, Ghost Whisperer) began making use of Callery’s musical skills, as well, leading to a professional friendship that continues to this day. “He needed someone to arrange some percussion tracks,” Callery says. “He’s really one of the true mentors and friends in my life.”

Callery briefly toured with Olivia Newton-John as her musical director, and created SFX for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, enabling him to develop hybrid sound design for his repertoire, which would come in handy on 24. Callery scored Newton-John’s 1990 Christmas movie (A Mom for Christmas) with composer John Farrar, and in 1996 Callery got his first true scoring opportunity for TV’s La Femme Nikita. After a five-year stint there, producer Joel Surnow brought him along to score his new Fox series, 24.

To work on the show, Callery converted the back house at his home in suburban West L.A. into a studio. The two-story structure was gutted and soundproofed, the latter at some expense. “I wanted to make sure noise was never going to be an issue,” he says of his residential studio.

At the core of Callery’s composing setup is Logic 7 (which he expects to upgrade to Logic 8 soon), along with a collection of favorite — mostly analog — samplers. While he uses Gigastudio and Logic plug-ins, such as LinPlug Albino and ProjectSAM Symphobia, it is in his rack full of analog gear that Callery finds many ingredients for the unusual sounds of 24.

“I like having a mixed bag of different gear from different times because it keeps the sound fresh,” he says. Included in the set are a Korg Trinity, Roland XV-5080, Yamaha CS6, Korg 01R/W (which provides a selection of bell sounds Callery uses often) and a Roland S-760, which, Callery notes, has a whopping 32 MB of RAM. “I load that up with old Roland samples because the analog modeling of the Roland machine is still really, really wonderful.”

The centerpiece of Callery’s sound-creating universe is a Synclavier DAW — an older-looking keyboard connected to a tower located in the studio’s machine room. Callery composes using an old Kurzweil PC2 keyboard; then the sounds and music are recorded to Pro Tools HD 7.3.1.

The composer creates rough mixes in the main studio through a Digidesign ProControl interface, simply to store his compositions in case of system failure or other catastrophe. But the heavy lifting is done by TV score-mixing veteran Larold Rebhun in a separate mixing room outfitted with a mirror-image Pro Tools setup. “The systems are networked, so if I finish scoring in the main room, I can save it and Larold can open it up in here and mix while I keep my compositional setup working,” Callery explains.

Rebhun can be counted on to mix between 25 and 40 minutes of score in a single day — no easy task for even the most robust of mixers. “He’s mixed for so many television shows, so I absolutely trust him,” Callery says. “For example, I always have high percussion way, way hot out there. But he knows that when the volume’s down in a track, that high percussion’s going to cut through a lot more than anything else so he’ll pull it down. He knows what he’s doing.” Rebhun and Callery provide anywhere from five to nine sets of stereo stems to Universal dubbing mixers Mike Olman and Ken Kobett, giving them the most flexibility for the effects-laden episode soundtracks.

After seven years of episodes, producers generally leave spotting to Callery and music editor Jeff Charbonneau, another X-Files veteran. “Jeff is one of the best editors I’ve ever worked with,” Callery says. “He has a great take on how to tell the story with music and when to come in and when to come out.” Charbonneau will most often take the first pass, and, while the two typically agree on spotting notes, Callery occasionally will suggest a different path.

While the pilot episode seven years ago required 23 minutes of music, Callery is called upon to write an astounding 41 minutes for typical episodes of 24 for a 44-minute episode. “Every year, the music has gone steadily higher in terms of the minute count,” he notes. “The initial ideas of ‘propulsion’ kept evolving, and the producers really like that — the idea that the clock’s always ticking.”

Between receiving the episode to delivery to the dubbing stage, Callery has only about five days to work. “I’ll get the show on a Thursday late afternoon, spotting will happen Thursday night and I’ll probably start the show on Friday. I’ll have about four-and-a-half days then to write it and another half-day day to mix.”

Callery will typically start with the most difficult scenes, leaving less-complicated cues for later. “When I have four-and-a-half days to compose and if I have an eight-minute action cue, it’s good to get that done because they’re more complex in terms of the sheer logistics of writing it and performing it,” he explains.

He says the more “routine” CTU/FBI scenes, in which Bauer and other agents might be discussing a plan of action to a tense background of pulsing rhythms, are not as simple to execute as it might seem. “We’ve done dozens of those scenes, which I love. But if you have a three-minute scene, you cannot just continue the same idea for the whole three minutes; you have to contrast it, introduce new sounds. It’s a matter of finding the right textures and using them sparingly, and not fatiguing the ear.”

While those types of cues are the mainstay of Callery’s work on the show, his action cues ratchet up the suspense for viewers. “People have told me that the music I create for the show resembles that of an action film, which is really a great compliment. Those films have big brass sections, big strings, trumpets, the whole big percussion and driving drums. And those scenes take a lot of time to build. But when they’re done right, they play out really well.”

A major part of Callery’s action palette is drums, sourced from favorite sounds, such as tom-toms in his Synclavier, combined with newer sounds from programs such as True Strike. And, like everything in his 24 scores, Callery performs them himself, using a MIDI trigger device or, more typically, his keyboard.

He also enjoys working on what he calls “subtextural” cues, which produce a sense of discomfort for the viewer. “I’ll be putting things in there that won’t necessarily have a melody, but they’ll have a sort of a sound that tweaks you and you don’t know why,” he says.

The effect of Callery’s music on the storytelling is obvious, not only to fans, but to show producers, as well. “Sean’s music really gives scenes their pulse,” executive producer Howard Gordon says. “He’s saved more shows than I care to count.”