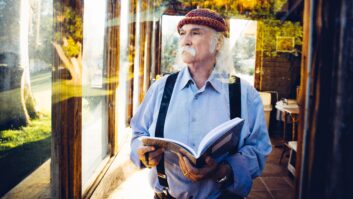

Photos and text by Mr. Bonzai

GRAHAM NASH

What was the genesis of the Crosby Nash album?

As usual, the genesis of any of our projects was “What music do we have

to make?” That’s the first consideration. And for this particular album, we

had what was for us an enormous pool to choose from—25 or 30 songs to work with.

How far back does the writing of these songs go?

Let me see, there’s one that was written the morning it was cut. There is

one of mine that I wrote when my son Jackson was one year old, and he is 26

now. It doesn’t matter to us when a song was written—is the song alive, does

it have a reason to be communicating to other people? Then let’s get on with

it.

Are all the songs written by you and David?

No, one of the great delights of this project was that we were completely

open minded as to who wrote what. Normally, people are very protective—”This

is my song and I need six songs on the album.’” Not us. In this particular recording

experience, we were completely open. For instance, “Milky Way Tonight” was recorded

the morning it was written. David had to go to a dentist appointment and we

were kind of stuck without anything to do for a couple of hours. We did have

plenty to do, but it was very technical and we just weren’t in the head space

for that. So, I said to the boys, “Look, I’ve got this melody and these two

verses, but it’s not finished. Let me just play you the two verses, because

at this point I don’t know where to go. James Raymond tried something and it

was really cool. So now we’ve got the two verses and the chorus, but it needed

to go somewhere else, and Jeff Pevar said, “Why don’t we go to the A there and

just stay there for four bars before you sing the last verse.” That’s how it

was done, that’s how it was finalized, and by the second take it was complete.

I heard a bit of “They Want It All.”

That’s a vintage Crosby attitude; it’s a brand new song about Enron. In a bigger picture, it’s about all corporate malfeasance, but inspired by the outrage that David felt about the way that Enron treated its employees and ruined countless thousands of lives, destroying their life savings and their IRAs and their 401s. But at the same time, making billions for themselves. David, of course, with all due disrespect, was outraged about that.

He sounds like a classic angry young man.

Yes, and in the ballad we were just listening to he sounds angelic—”Through

Here Quite Often,” lyrics by David, music by Dean Parks. An unbelievably beautiful,

heartbreaking song, about David’s observations in a coffeeshop, watching this

waitress who was incredibly kind to people in very small ways—the way she handed

someone a fork, and didn’t throw it on the table. Small moments of kindness—David

picked up on it and wrote the words.

“Jesus of Rio,” Is that your song?

Melody and words by me, and the guitar chords by Jeff Pevar. I was so thrilled with the way that Pevar put the chords to my melody, because I’m just not that kind of a player, that I gave him 50 percent of the song.

[Tell me about] this alternate environment you’re working in, [Center Staging].

It’s a rehearsal hall—it’s quite simple. We have rehearsed here before with

David and his band CPR, and with Crosby, Stills and Nash many times. We’ve been

most comfortable here. The people who run this establishment know what musicians

are all about. They know what they want, and know what they don’t want.

So you’re not missing anything.

I’m not missing anything. When we told Nathaniel [Kunkel] that we were

most comfortable here, he said, “Then that’s where we’ll record.” And that’s

how it was.

Where is Stephen?

The truth is that we have always mixed and matched in various combinations

throughout our musical lives. It’s been Crosby, Stills and Nash, and Crosby, Stills,

Nash and Young, and Crosby/Nash. Stephen and I have done a couple of things together.

Neil and I have done a couple of things together. We started out by saying, “Listen,

this is just four guys. We are not a ‘band.’ We will make music with whomever

we wish, because we are following our hearts, and our musical instincts, chasing

the muse down. In this particular experience, we haven’t had to chase the muse

down. The muse has been banging on the door. This has been three solid weeks of

absolute delight.

Will you mix it on your own Studio Without Walls, a mirror image system

of this one, that Nathaniel put together?

That’s right. He put together a mirror image system at my home in Hawaii

that you came to and documented and that is where we will mix it. Why not? Why

not mix in paradise? We are not stuck to a studio—all we need to know is what

are these speakers and does Nathaniel know what they’re supposed to sound like.

The rest is arbitrary—whether the walls are two inches out of square with standing

waves, or any of that stuff. It doesn’t matter anymore.

Tell me about the band on this album — Lee Sklar?

Lee Sklar is without question, in my mind, one of the most musical, most intelligent

bass players on the face of the earth. His earliest instrument, which he was extremely

good at, was classical piano. He turned to the bass, mastered the bass, and as

well as keeping an incredibly great groove, he is lyrically unbelievable in his

bass playing.

Dean Parks?

What can you say about Dean Parks? He’s played on a million records; loves music to death—it’s in his soul, he can’t do anything about it, and I love him dearly. The man has taste for playing parts with multiple instruments—keyboards, bass, guitars—and the guy has a sense of record-making that is unparalleled.

Your drummer?

I’ve known Russell [Kunkel] since he was 19 years old. I have a telepathic connection with him, and Crosby had it as well, before he turned me onto Russell when he was in a very early band in the late Sixties. He’s been one of my favorite drummers for a long, long time. He was on every Crosby Nash record that we made, and he was the drummer in the 1974 stadium tour that CSNY did, so we go back a long way. Incredibly cognitive of where not to play—what’s very important in a musician is the breathing space. Anyone can play all over things, anyone can be flashy and look groovy. Russell plays the song.

Jeff Pevar?

What can you say about Pevar? An unbelievable guitar player, incredibly

adept at what he does. He gives his heart and soul and takes direction unbelievably

well. Obviously he plays with David in CPR—he’s the P in CPR, and a delight

to work with. It’s great to have both Pevar and Dean Parks in the same band,

which was actually my live band when I went out on the last tour for Songs

for Survivors, along with James Raymond, Russell and Larry Klein on bass.

James Raymond?

You mentioned “Jesus of Rio.” It called for a little piano solo, but in

warming up to do it, he started to play this unbelievable jazz influence, with

echoes of the chorus. Russell said, “Stop, let’s record. Give me four takes

like that. Keep it to about a minute.” James wrote an improvisational piece

that we then stuck at the front of the song, and it’s fabulous. James Raymond—watch

out, this kid is a brilliant musician.

Who is the producer of this album?

Russell and Nathaniel are the producers, and David and I are helping them.

The production credit will be: Crosby, Nash and the Kunkel boys, and the engineering

is purely Nathaniel.

And remember how we were talking earlier about the distance from the idea and the music? It involves a lot of people, mainly Nathaniel, but Nathaniel’s assistant Kevin Plessner has also been very important here. He has facilitated shortening the distance between the idea and the music and that’s very important. The kid’s sharp. He’s got a good future.

DAVID CROSBY

Are you pleased with the project here?

Yes, and Nathaniel is old enough now that you can’t call him a child prodigy, but coming from where he comes from, and having watched him since he was born, I’m astounded with how he turned out. He did something really smart when he apprenticed himself to George Massenburg, because he learned why everything does what it does, not just how. He knows why. But what he’s done that has really set him apart from everybody is twofold. One, he was raised around music, so he is tremendously musical. He listens to a song not as being sonically gorgeous, but does it out of content being content. And he understands that — very few technical guys understand it. He understands it completely. Secondly, technically, Pro Tools is an interface and he has learned to work that interface more skillfully than anybody else I have ever seen…and he has an astounding memory. Most people have to sit there and write down the words, and then do a comp track of four vocal passes. Nate has them memorized. He can say, “that phrase is better in the second [take] remember?” You say, “How do you know that?”, and you go back and he does. I think the reason he is so good is multifold. He is technically incredibly proficient, not just in how he does it, but because he knows why everything works. I think he is musically and artistically one of the most advanced engineers I have ever met in my life. He really gets what the content of a song is, and he understands what you are trying to do.

How do you like recording in this improvised environment?

I couldn’t imagine doing it any other way now that I’ve done it this way. The communication is so much faster and clearer, and the proof is in the pudding. We cut an astounding amount of tracks in a very short amount of time, and they were not easy. You heard these songs—they are complex, these are not easy things to do. And I think it made everybody in the room conscious of each other, conscious of the song. You could not get off on your own little world, playing your own hot licks. It was a unifying factor to do it in this way and I think it works brilliantly. I can’t imagine what it’s going to be like in the future, but I know this would be my preference for how to do it.

NATHANIEL KUNKEL

Why did you choose to record in this way?

We are always cutting live, even if you are in a studio and you’re going

for a live take, so ultimately getting comfortable is the most important thing.

My studio package is really quiet, so it was easy to have it in the corner of

the room as long as I turned the speakers down. This type of environment allows

everyone to be very comfortable. Whenever I felt like it, I could move around

and create, and the musicians could pick an instrument up and start playing.

You could immediately decide you wanted to record in that place. You can do

anything you want.

Any isolation problems?

Well, sure, but the musicians weren’t playing things that I would replace later on. On the very first day, we got together and I said, “You have to be logical. If you want bashing drums and really loud guitar and piano, you can’t cut them all at the same time. There is no way to isolate the drums from the piano in the same room. We can baffle off the guitars from the drums, but you can’t do it with the piano.” For a quiet acoustic guitar, we put it in the iso booth. You have to use your head because you are not in a traditional recording studio, but you can work anywhere you want and capture any moment that is being created.

When we got started, the musicians were still learning the songs. We had thought

about rehearsing all the songs and then starting the recording sessions, but

I suggested that we just set up and as soon as we had the take rehearsed, we

just record it. Studio time is so expensive these days, you really need to get

in and get out.

Was there something special with the headphone configuration?

This aspect of the project was very cool. You have a head unit that you plug 16-channels into and there is a CAT5 Ethernet cable that goes to a router with power. Then you have eight outputs from the router and you have as many as you want. Each one of those outputs can connect with an Ethernet cable and a little headphone mixer and everything, including power and 16 tracks of audio, is carried over one cable. We had a router in the corner and everyone had their own headphone mixer. They could change the levels, and save and recall their own mixes. Since it was Ethernet, we put 50-foot cables on all of them so people could move around and take their headphone box wherever they wanted. Everything was up all the time, so if someone wanted to turn up the acoustic guitar knob and hear themselves, they could.

Now that you’re finished recording, how does it feel?

This project unfolded in such an unbelievable way—the quality of the recording

and the quality of musicianship, the songs, the singers, all of it worked out

so well. I am as proud of this as anything I’ve ever done.

Find out more about Kunkel’s studio at www.studiowithoutwalls.com.