For anyone who wasn’t alive to witness their ascent, it’s nearly impossible to picture a time when The Beatles were “simply” a popular teen act and not the cultural monolith that is THE BEATLES. That transition from boy band to revered artists didn’t happen in public, however; it took place far from the fizzy lights of showbiz, inside the comparatively stodgy confines of Studio Two at Abbey Road Studios. It was there that the group knocked out a jaw-dropping 116 tracks between 1963 and 1966—a musical tidal wave that culminated with the sea change that was Revolver.

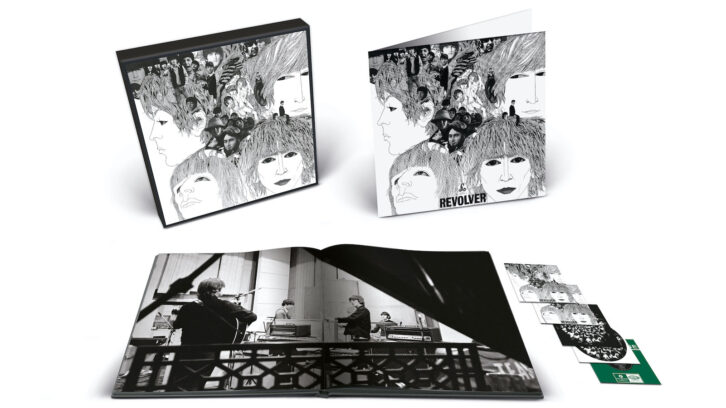

That record would propel the Beatles away from the sounds of their past, and set the table for the boundary-pushing albums yet to come. The ‘how and why’ of that happening is now the subject of a massive new “Special Edition (Super Deluxe)” box set, released October 28, that recontextualizes Revolver while also revealing how it was created. Simply put, the new collection is a must for audio pros looking back for insights, inspiration or just some good listening.

The centerpiece of the Revolver box set is a new stereo mix created by Sam Okell and Giles Martin, son of the Beatles’ famed producer, George Martin. That’s supplemented by two sets of outtakes, rehearsals, demos and studio chatter; the album’s original 1966 mono mix; and a contemporaneously recorded single, presented in original mono and new stereo mixes. All that is accompanied by a hard-bound, 100-page book that leaves no stone unturned in detailing the album’s history. The full box set is available in both vinyl and CD formats, but other iterations are also available—two CDs with the new stereo mix and Session highlights; the new mix on CD or LP; and a digital-only edition, which adds a Dolby Atmos mix not available on a physical format.

As box sets go, the Revolver “Special Edition (Super Deluxe)” collection has its work cut out for it, as it must satisfy everyday Beatle fans and yet also cater to those who examine every lyric and note with the rigor of an academic scholar. It has to revitalize some very familiar music, and then document how that music was created without getting so deep in the weeds that it kills whatever excitement it creates.

The revitalization aspect is handled well. The music has been readily available for more than 50 years, so giving it a new stereo mix makes sense. Since the Beatles recorded Revolver with a mono mix in mind, the original stereo mix was essentially an afterthought, but with the stereo format going mainstream in the decades since, the mono mix fell by the wayside and the comparatively slap-dash stereo mix became the better-known version. The new current-day stereo mix, then, honors the original editions while taking better advantage of the stereo format to meet the consumer expectations that come with 50-plus years of improvements in home audio.

That new mix was made possible due to advancements in de-mixing made by director Peter Jackson’s WingNut Films production company, which created proprietary technology to take apart sound from hundreds of audio tapes to reveal the audio used in his 2021 documentary, The Beatles: Get Back. As Giles Martin explains in the box set’s book,

“Revolver was recorded on one-inch four-track tape – primarily to be mixed to mono and then additionally in stereo for general release. The band, as always, played live, often recording everything to a single track. This means that when the record is mixed, there is no option to place an individual sound in a stereo – or, these days, a spatial – audio field in order to hear it as it was in the studio. Last year, working with Peter Jackson’s audio team led by Emile de la Rey, we embarked on de-mixing The Beatles’ four-track Revolver tapes. Separating the individual, recorded elements was done not to change the sound but to give us some flexibility, so we’re able to hear the album in a new way. For the first time, we had the band playing together in the studio, but on different tracks.”

The demixing technology allowed the engineers to create a new stereo mix, but it also paved the way for the rest of the box set as well. Hand-in-hand with The Beatles’ extreme popularity, they are the most bootlegged act ever, and nearly every note they recorded in the studio has leaked out at some point or another, regardless of how insignificant it might be. By applying the demixing process to demos, outtakes and so on, however, the engineers provide a brand-new look at the album’s creation that hasn’t been bootlegged—and which sounds better than any boot would anyway.

And those sounds are something to behold. By 1966, The Beatles’ success had taken the group around the world, exposing them to more varied culture and art than most of their contemporaries. With their ceaseless musical curiosity and unstoppable career aspirations, it was perhaps inevitable that Lennon, McCartney and Harrison would start to incorporate the art they’d been exposed to into their own work, with Lennon adapting Avant Garde approaches to lyric writing, Harrison exploring the music of India after encountering a sitar on the set of Help, and McCartney drawing on everything from old-school vaudeville to Stockhausen.

That sense of experimentation continued on from the songwriting process into Abbey Road, as is well-documented in the box set’s book. While typical Beatle fans may skim the tech-ier parts after a few minutes, there’s a bumper crop of information for recording-minded readers, such as when engineer Ken Townsend shares in depth how he created ADT (Automatic Double Tracking). There’s also a paean to the Fairchild 660 limiter, detailed explanations of how moments like George Martin’s piano solo on “Good Day Sunshine” were taped at 7.5 ips and then played back at speed, and much more. In an extended look at how “Yellow Submarine” was recorded, Townsend recalls one such moment:

“When John [Lennon] climbed up the steps of Studio Two and entered the control room, he would often come up with a poser. In this session, he asked, ‘How can we get an underwater sound?’ My solution was to fill a quart milk bottle with water and insert a KM53, our smallest microphone. It was wrapped in the polythene bag my wife had used to pack sandwiches for me. With an all-round configuration, they were able to sing around it. It was not just The Beatles who were crazy!”

As might be expected, there’s also a sizable section on recording the landmark psychedelic track, “Tomorrow Never Knows.” That session just happened to be 20-year-old Geoff Emerick’s first day on the job as sound engineer—a day that found him faced with Lennon’s enigmatic request, “I want to sound like a Dalai Lama singing from a hilltop.”

However, that’s par for the course, as seemingly every song in the box set has a surprising engineering story behind it, whether it’s George Martin putting Lennon’s vocals in reverse at the end of “Rain” on the contemporaneously recorded single, or its flipside, “Paperback Writer,” where the engineers worked around EMI’s ultra-restrictive technical specs, using a giant loudspeaker as a mic to create McCartney’s huge bass guitar sound.

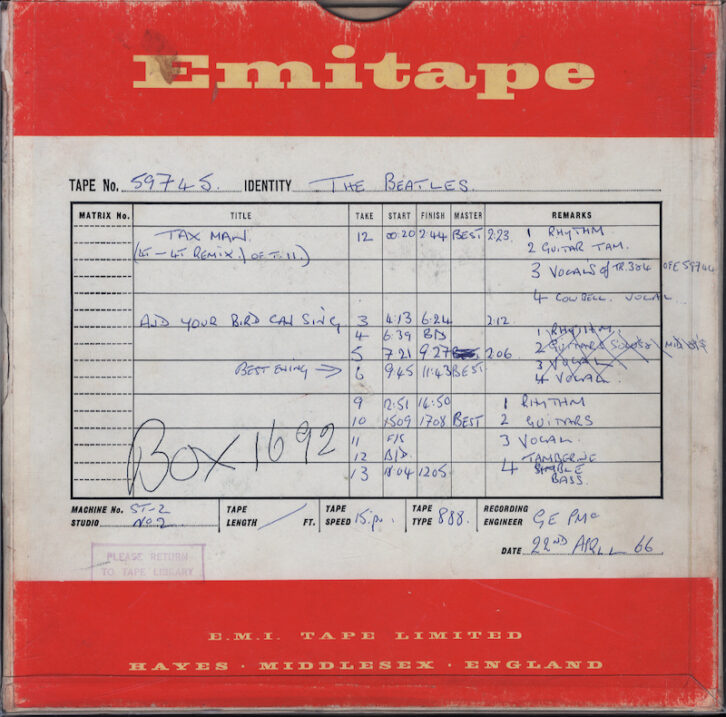

While all this and more is found in the book—lavishly illustrated with session photos, tape box covers, tracking sheets, studio layout diagrams and more—it is, of course, secondary to the music. The tome may give listeners clues about what to listen for in the outtakes, but explaining what the musical achievements are and why they’re important isn’t merely a matter of education; it’s fun. Understanding not only what you’re hearing, but how it was created—and in some cases, what it would be further turned into—is eye-opening. It takes these familiar songs out of the museum-display case of the mind, and reverts them back into living documents, to once again be heard and enjoyed before they are carved into stone by time and omnipresence. You gain new appreciation for not only the accomplishments of the all-star recording team around the Beatles, but also the band itself as master musicians who were sticklers for working over a song until it was right.

The Revolver box set meets all expectations, and is worthy of the expanded Beatles discography, providing new ways to look at a much-vaunted album. For audio pros, however, it has the added feature of documenting one of the most important moments in recording history, when the biggest band in the world began to treat the studio itself like an instrument for the first time.